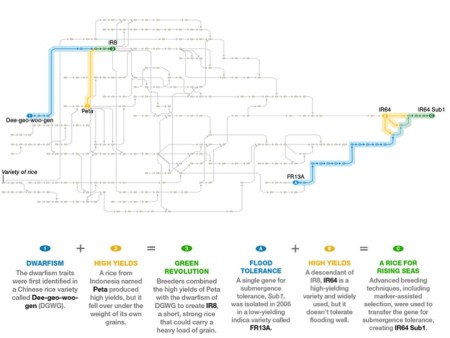

Well, actually the quote in National Geographic’s blockbuster on food — The Next Green Revolution ((This seems to have come out last September, but for some reason completely passed us by. I guess we must have been busy with work or something, though that sounds unlikely.)) — is “Mihogo ni kila kitu,” which means “cassava is everything” in Kiswahili. I changed it to “rice is everything” because I want to highlight the illustrations in the article that shows the pedigree of IR64 Sub1, IRRI’s famous flood-tolerant rice. There’s also fun stuff in the article about cassava, and other crops, but I’ll leave that to you for now.

You know we’re great fans of pedigree diagrams here on the blog, because they’re so good at showing how important it is for crop breeding programmes to have ready access to the widest possible range of genetic diversity, from as many different places as possible, preferably in a genebank. Anyway, I don’t of course know what it looks like on your screen, but on mine the illustration was disappointing. If you see the whole pedigree, then you don’t see the caption; if you get one of the captions, then you only see part of the pedigree; and you can’t see both captions at once. So I’ve taken the liberty of putting the whole thing together. Here it is. You can click on it to see it better. I hope you like it. And I hope National Geographic doesn’t sue us.

Try this relationship: monodominance + high yields = a crop to feed the world. Specifically the ability of irrigated rice to grow in monocultures to make it a super-crop. I think we can make the case for early rice farmers finding a gene – let’s call it `mon 1′ – in a wild relative and nurturing the product without the benefit of formal plant breeding. And wild relatives certainly were persistently monodominant (despite the claims of so-called `agroecologists’ that such was somehow unnatural).

For example: Prain [Flora of the Sundribuns. Records of the Botanical Survey of India 1903, 231–370, p. 357] described the ecology of Oryza coarctata, a wild relative of the world’s most important food crop, rice. It was the most common and most plentiful grass species in the Sundarabans mangrove swamps of Bengal and:

If a wild plant can manage that, it could give a hint to early farmer-ecologists trying to grow rice.