- Deeper roots could store CO2 and resist drought? Well, yeah, I suppose. Need to find the original paper.

- Commodity price volatility 101; off topic, but important.

- Good return on investment for agricultural aid in Togo. Some vegetables included.

- Stuart Pimm answers “why should I care” questions about biodiversity. No time to listen, so no idea whether he does any agrobiodiversity.

Onions evaluated “for food security”

Scientists at Warwick University’s Crop Centre have examined “96 of the world’s onion varieties” for resistance to basal rot (caused by the ubiquitous Fusarium oxysporum) and their ability to form close relationships with certain beneficial fungi. The press release doesn’t go into any detail, such as which varieties top the lists, or anything useful like that, although it does raise some questions. Like, where were the onions from? Andrew Taylor, the researcher in charge, said this:

“We have developed a unique onion diversity set from material sourced from across the globe. We now have a extremely useful library of the variation in traits … all of which will be extremely useful to growers and seed producers dealing with changing conditions and threats to onion crops.”

Spiffy. And a nice alternative, eventually, to current control methods. But what exactly is this “unique onion diversity set”. Is it, by any chance, anything to do with the Allium collection maintained at the old UK National Vegetable Collection at Wellesbourne, recently threatened with closure? And if so, why wouldn’t that have been mentioned by the Warwick Crop Centre, which absorbed Wellesbourne and its Genetic Resources Unit? Surely anything good that comes out of the Wellesbourne genebank is an argument for continued support.

On a purely personal note, I’d love to know whether two varieties, Up-to-date and Bedfordshire Champion, were among the 96 that were evaluated. That’s because in 1948 the UK Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food noted that Up-to-date had excellent resistance to white rot, while Bedfordshire Champion was highly susceptible. In the mid 1960s, MAFF decided they were the same variety, under synonyms, and dropped Up-to-date from the National Catalogue.Wellesbourne did maintain it, and it would be interesting to know whether the two had different profiles in this latest round of evaluation.

Nibbles: Pastoralism, Carnival, Mustangs, Cassava, Tea, Biofuels

- Pastoral mobiity “a trump card to be strengthened”.

- Latest Berry go Round is up, although I can’t actually read it myself.

- Wild horses in the US southwest.

- Cassava notes: GMO cassava lower in cyanogens, higher in protein.

- Climate change threatens Ugandan tea. Luigi’s MIL secretly pleased.

- How to guarantee a food-insecure future in Kenya.

Famine and diversity

The famine unfolding in Africa is rightly dominating news and comment around the world, the more since it is now “official”. One recurrent theme is that the disaster could have been, and was, foretold … and ignored. Jeffrey Sachs says he warned the US President.

[T]wo years ago, in a meeting with US President Barack Obama, I described the vulnerability of the African drylands. When the rains fail there, wars begin. I showed Obama a map from my book Common Wealth, which depicts the overlap of dryland climates and conflict zones. I noted to him that the region urgently requires a development strategy, not a military approach.

Obama responded that the US Congress would not support a major development effort for the drylands. “Find me another 100 votes in Congress,” he said.

I shouldn’t think the votes are there now, either, but Sachs’ fourfold prescription remains at least partially valid. Whether this particular drought can be laid at the door of climate change is not relevant; climate change will make droughts (and floods) more severe an we need to deal realistically with the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving climate change. Fertility rates are high, but if history is anything to go by, they won’t come down until living conditions and prospects improve. The region is poor and so, as Sachs notes, shocks that other regions might shrug off push it towards calamity. And unstable politics exacerbate the other problems; food security is hard to achieve in a region without other forms of security.

The big question is what sort of development strategy would work best in the region. Sachs, naturally enough, favours something like the interventions going on in the Millennium Villages Project. None of those, however, seem to me to address the root problem, which is that the land is too dry and too unpredictable to support anything other than pastoralism, and that pastoralism is a victim as much of modern geopolitics as it is of climate change. I have no idea what to think when I read things like this:

The government [of Kenya] has announced plans to immediately put 10,000 hectares of land in the River Omo delta around Lake Turkana under irrigation to produce maize, sorghum, vegetables and fruits to ease the food crisis frequently experienced in the region.

Can that possibly be the right approach? It seems very unlikely. Meanwhile, I’ll keep an eye on the information being shared at ILRI’s newsy blog.

Old specimen is new melon crop wild relative

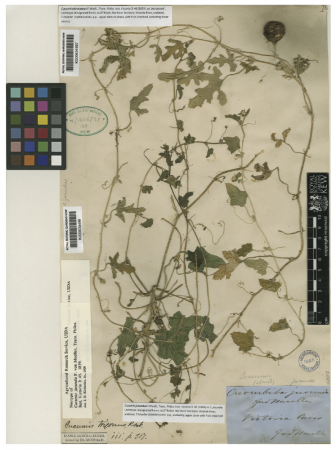

![]() Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding.

Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding.

A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

Fast forward 160 years or so, past a few older taxonomic revisions, and you get to one based on molecular analysis that splits the two previously recognized species of Cucumis in Asia, the Malesian region and Australia into 25 species. By this analysis Australia harbours seven species of Cucumis, five of them new to science. C. picrocarpus is one of the two previously recognized species, and the molecular analysis reveals that it is actually the closest wild relative of the cultivated melon, C. melo.

So what? Quite apart from the necessity to call things by their correct names, cultivated melons are besieged by many economically important pests and diseases. It seems likely that, as so often, resistance will come from a wild relative. Which means it is good to know exactly which plant is the closest wild relative. So what’s the status of C. picrocarpus in the wild? I have no idea, alas. I couldn’t find any entries in GBIF (possibly because they are all subsumed under C. melo) and with Luigi gone temporarily to ground I’m not sure where else to look. It seems a fair bet that it might need protection, although I’d be delighted to be wrong.