- GM canola goes wild, Jeremy is not surprised

- More — much more — on maize cultivation in Chaco Canyon.

- Conference in London on Securing Future Food. Agrobiodiversity should be present.

- Chefs embrace agrobiodiversity — in Maine.

- Price spikes: climate change or knee-jerk policies? (Both?)

Sub-Saharan strategies for climate change adaptation

IFPRI has just published a review of the strategies that the 10 countries that make up ASARECA, the Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in Eastern and Central Africa, plan to use to adapt to climate change. Only two strategies are common to all 10 countries: “the development and promotion of drought-tolerant and early-maturing crop species and exploitation of new and renewable energy sources”. Leave aside that the second strategy encompasses biofuels, and there’s still something else striking about the strategies.

Strangely, only one country recognizes the conservation of genetic resources as an important strategy although this is also potentially important for dealing with drought.

That country is Burundi, which we heartily applaud.

The point is not that each country should independently set out to conserve genetic resources; that would be inefficient and wasteful. But they ought at least to acknowledge the importance of conservation. And ASARECA could, at the very least, promote the International Seed Treaty and encourage members to prioritize collection of the most threatened crops and wild relatives. IFPRI could help by recognizing that genetic resources — agricultural biodiversity — underpin far more of the strategies than adaptation to drought.

Nibbles: FARA, Khat, Pepsi in Peru

- Another blog about FARA’s 2010 meeting, this post features our friend Ehsan Dulloo. (Where’s an aggregator when you need one?)

- Mikrokhan masticates the khat economy. Would it really not grow locally?

- PepsiCo invests USD3 million over 3 years in Peruvian potatoes. Why not use CIP?

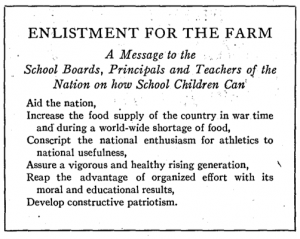

Farming and schoolchildren

I had really hoped to find something strikingly modern in a pamphlet linked by Marion Nestle, so that I could challenge you all to guess when it was written. Alas, it is too steeped in the language and context of its time. In 1917 John Dewey, the noted psychologist, educator and general all-around thinker, was urging the schools of America to encourage pupils to garden.

I had really hoped to find something strikingly modern in a pamphlet linked by Marion Nestle, so that I could challenge you all to guess when it was written. Alas, it is too steeped in the language and context of its time. In 1917 John Dewey, the noted psychologist, educator and general all-around thinker, was urging the schools of America to encourage pupils to garden.

There will be better results from training drills with the spade and the hoe than from parading America’s youngsters up and down the school yard. 1

He adduces many convincing arguments which could, with a minor rewrite, be deployed today. Indeed, Nestle makes the connection between child nutrition bills “languishing in [the US] Congress” and Dewey’s exhortations. My question is: did they work then? A quick search reveals that Dewey’s ideas about experiential learning influenced at least a few current school gardens. However, there’s no easily-unearthed evidence that American schools took up farming and garden in 1917-18. Now if only Dewey had had an impact pathway.

Nibbles: Iron beans, Tomatoes, Fruit, Africa college

- Learn about iron beans from a HarvestPlus video, maybe.

- Learn about the tomato in Ghana, more than you might need to know if you read all the reports.

- Learn how Andy Jarvis spoke truth to ex-power, about fruit data gathering project prospects.

- Learn how the Africa College, based at Leeds University in the UK, is working on a range of agricultural problems.