- A way out of hell: workshop on Database Challenges in Biodiversity Informatics

- Potato man honoured.

- Farm diversity reduces nitrogen runoff.

- Darwin on the Farm, from our friends at the Global Crop Diversity Trust.

- Yeast and wheat genome sequencing going gangbusters.

- Coffee!

- Fermented tigernuts more nutritious? No, they’re not from an endangered species. Via.

- Cow water!

- Lots of medicinal plants conservation projects going on in India.

Blogging the big birthday: Beans and selection

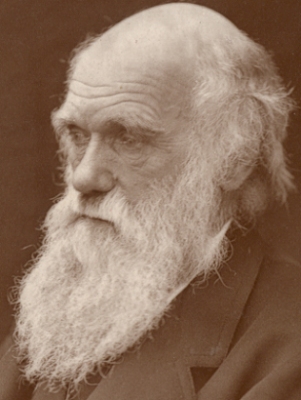

Given that he wrote an entire book on The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, Charles Darwin offers us a rich seam to mine. 1 I was particularly struck by a phrase I thought I heard Professor Steve Jones use in the recent special series of In Our Time on BBC Radio 4, when he referred to Darwin’s garden at Down House as, I think, the Galapagos of Bromley. His point was that Darwin’s experimental work and observations in his garden informed his ideas no less than his journey.

Given that he wrote an entire book on The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, Charles Darwin offers us a rich seam to mine. 1 I was particularly struck by a phrase I thought I heard Professor Steve Jones use in the recent special series of In Our Time on BBC Radio 4, when he referred to Darwin’s garden at Down House as, I think, the Galapagos of Bromley. His point was that Darwin’s experimental work and observations in his garden informed his ideas no less than his journey.

There is a good deal in The Variation … about how plants change in their characteristics, from presumed differences among the maize varieties of New England and Canada to the northward progress by “thirty leagues” of the northern limit to growing maize in Europe, over a period of about 60 years. “[I]n Sweden,” Darwin writes, “tobacco raised from home-grown seed ripens its seed a month sooner and is less liable to miscarry than plants raised from foreign seed.”

These, and many others, are typical of the observations of others that Darwin accumulated and scrupulously credited. But he made his own observations too.

On the same day of the month [24 May], but in the year 1864, there was a severe frost in Kent, and two rows of scarlet-runners (P. multiflorus 2) in my garden, containing 390 plants of the same age and equally exposed, were all blackened and killed except about a dozen plants. In an adjoining row of “Fulmer’s dwarf bean” (P. vulgaris), one single plant escaped. A still more severe frost occurred four days afterwards, and of the dozen plants which had previously escaped only three survived; these were not taller or more vigorous than the other young plants, but they escaped completely, with not even the tips of their leaves browned. It was impossible to behold these three plants, with their blackened, withered, and dead brethren all round them, and not see at a glance that they differed widely in constitutional power of resisting frost.

Darwin doesn’t there make the point that the survivors of such a killing frost might give rise to more frost-hardy offspring in due course. And I have not been able to discover whether he asked his gardeners to save seeds from those that had survived. I like to think he did. In The Origin (p 142) he very clearly anticipated such an experiment:

[U]ntil some one will sow, during a score of generations, his kidney-beans so early that a very large proportion are destroyed by frost, and then collect seed from the few survivors, with care to prevent accidental crosses, and then again get seed from these seedlings, with the same precautions, the experiment cannot be said to have been even tried. Nor let it be supposed that no differences in the constitution of seedling kidney-beans ever appear, for an account has been published how much more hardy some seedlings appeared to be than others.

This last may be a reference to a sharp frost on the night of May 24th, 1836, near Salisbury, when “all the French beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) in a bed were killed except about one in thirty”.

There is much, much more in The Variation … to amuse and instruct anyone with an interest in agricultural biodiversity. What I find odd is that despite the prevalence of seed saving in mid-Victorian England, Darwin was not able to prove to his own satisfaction that the beans of his own era were in fact hardier than those of previous times. Today’s scientifically informed seed savers ought to find it easy. Have they?

Blogging the big birthday: A taste of things to come

Tomorrow we will be celebrating the 200th birthday of Charles Darwin. Here’s a little foretaste:

Gallesio gives a curious account of the naturalisation of the Orange in Italy. During many centuries the sweet orange was propagated exclusively by grafts, and so often suffered from frosts that it required protection. After the severe frost of 1709, and more especially after that of 1763, so many trees were destroyed that seedlings from the sweet orange were raised, and, to the surprise of the inhabitants, their fruit was found to be sweet. The trees thus raised were larger, more productive, and hardier than the former kinds; and seedlings are now continually raised. Hence Gallesio concludes that much more was effected for the naturalisation of the orange in Italy by the accidental production of new kinds during a period of about sixty years, than had been effected by grafting old varieties during many ages. I may add that Risso describes some Portuguese varieties of the orange as extremely sensitive to cold, and as much tenderer than certain other varieties.

From The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication (1868, p 308)

And in an astonishing display of the power of Google, Serendip, and my dodgy memory, the same Gallesio (seen above) chronicled the Citrangolo di Bizzarria, noted by Luigi almost two weeks ago.

Blogging the big birthday: One man’s selection

As the entire thinking world prepares to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin, tomorrow, lots of people (ourselves including) are unable to contain themselves. One of those is R. Ford Denison, who shares a selection of Darwin quotes that he was preparing to take to a celebratory dinner. A great selection it is too, revealing Denison’s own status as a man who takes evolution in agriculture very seriously. I wouldn’t say that this was my own favourite, but it is one that I had not noted before:

Look at a plant in the midst of its range, why does it not double or quadruple its numbers? We know it can perfectly well withstand a little more heat or cold, dampness or dryness, for elsewhere it ranges into slightly hotter or colder, damper or drier districts. In this case we can clearly see that if we wish in imagination to give the plant the power of increasing in number, we should have to give it some advantage over its competitors, or over the animals which prey on it.

There’s more where that came from.

Nibbles: Bananas, Sorghum, Agave, Big vs small, Cauliflower, Wine, Chestnut, Farmers’ rights, India, Aquaculture, Medicinals, Tarpan

- How they grow bananas in Fadan Karshi, Nigeria.

- How they grow sorghum in Karamoja, Uganda.

- How tequila is ruining small farms in Mexico. Or is it?

- How small farms cannot feed Africa. Or can they? Join the debate! Via.

- How the Brits plan to rebrand cauliflower. This I gotta see.

- How the ancient Chinese made wine out of rice, honey, and fruit. Pass the bottle.

- How Georgia is mapping where its chestnuts used to be.

- How farmers’ rights are being implemented.

- How Indian agriculture should move beyond wheat and rice. Ok, but what would everybody eat?

- How microsatellites can be used to help catfish breeding.

- How Ni Wayan Lilir is helping people learn about the traditional healing herbs of Bali.

- How the Brits brought back the Konik.