- Red bananas: one man’s story.

- Avocado mayonnaise: one woman’s story.

- Terra Madre, Day 1: one man’s story. Almost like being there.

- Indoor hot pepper: someone’s grandad’s story.

- Sweet potatoes: several people’s stories.

What is a landrace anyway?

When plant genetic resources people are tired and emotional, and sometimes when they’re not, talk can turn to landraces. What are they? Can they be identified unequivocally? Can they be associated with a geographical location? Are names anything other than a convenient fiction? Whole chapters, if not entire books, have been written on the subject. 1 There are definitions aplenty, of course, but that’s not the same as an answer.

Wrapped up in the definitions, and the answers, are notions of genetic variability within the landrace population and an element of selection being needed to maintain the landrace’s properties and maybe guide it in new directions. But that, of course, is crucially affected by the breeding biology of the species concerned. Bluntly, species that are reproduced clonally, like figs, say, or potatoes, are unlikely to have any variability within the landrace while those that are obligate outbreeders, such as maize, are going to be much more variable within the population and likely to change over time too. And then there are inbreeders — beans like Phaseolus vulgaris — in which the landrace is probably a mixture of different genetically pretty uniform types, each of which may well breed true, although the proportions of each may vary from season to season and from place to place.

All of which is a long and roundabout introduction to three recent papers in Theoretical and Applied Genetics that tackle the problem of landrace identity, all of them using molecular markers.

Oat (Avena sativa) is normally self-pollinating, but occasional crossing does occur. So we would not expect much variation within a population. Good thing that, because Hermann Buerstmayr and his colleagues sampled DNA from only three individuals in each of 114 oat varieties gathered from around the world. 2

Nibbles: Funding, Cow Gods, Ãœber Bee, Rice, Bushmeat, Oaks

- $50 million for climate change. Must be some for agricultural biodiversity. Via, which has the application forms.

- How the Egyptians came to venerate cattle.

- Building a better bee.

- Official US rice harvest forecasts 20% too high. Chinese comment: “Without rice, even the cleverest housewife cannot cook.”

- How about without bushmeat?

- IUCN lists endangered oaks. Know any ex situ collections? Tell IUCN!

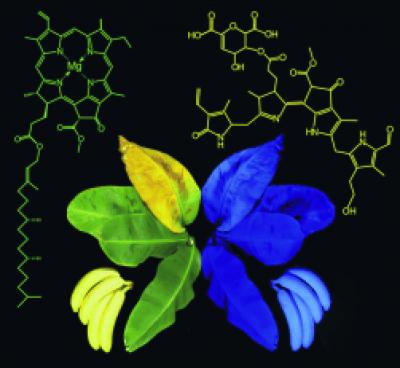

Blue bananas

Ripe bananas are of course yellow. However, under black light, the yellow bananas are bright blue, as discovered by scientists at the University of Innsbruck (Austria) and Columbia University (New York, USA). The team, headed by Bernhard Kräutler, reports in the journal Angewandte Chemie that the blue glow is connected to the degradation of chlorophyll that occurs during ripening. In this process, colorless but fluorescing breakdown products of chlorophyll are concentrated in the banana peel.

I kid you not.

Pollinator decline has no effect on global yields

Nature is reporting on a study that shows that “bees and many other insects may be in decline almost everywhere — but agriculture that depends on pollinators has been surprisingly unaffected at the global scale”. I have not seen the original paper, and I doubt that I am competent to assess it. But the report in Nature is intriguing. Using the FAO’s comprehensive dataset, Alexandra Klein and her colleagues observe no difference in yield patterns between crops pollinated by insects and other crops. There are other comparisons too, but the bottom line seems to be that local declines in yield with declining pollinators are not mirrored globally.

That’s no reason to relax, though.

Klein says her findings do not necessarily negate that idea that the world is in the throes of a pollination crisis. The data might hide how farmers have adapted to the problem, she suggests.

Nature goes on to suggest that a threshold-based catastrophe 3 may be around the corner.

Anyone care to comment on Klein’s paper? Or has Nature got it entirely right?