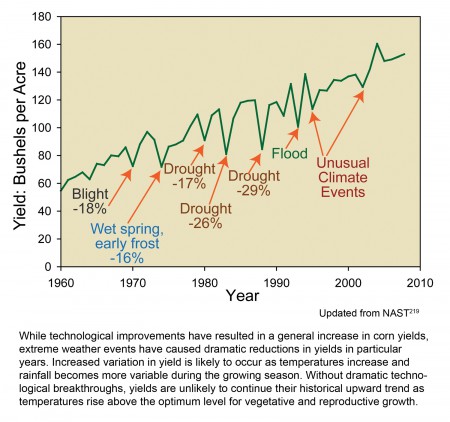

The Southern Corn Leaf Blight epidemic that struck the US in 1970 is usually seen as a canonical example of the dangers of genetic uniformity. I use it that way myself, often. Certainly yield losses in 1970 seemed very high, higher than the average 12% “expected from all diseases of corn”. But could we all be wrong? A commenter thinks so.

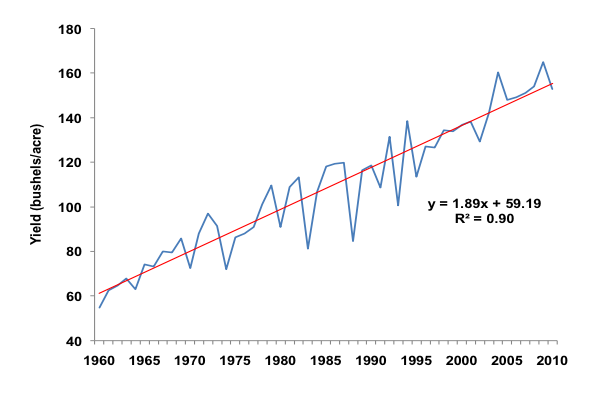

[W]as it a major problem? Over twenty years ago I gave a seminar at CIMMYT. I had prepared a slide showing the year on year average yield increase in maize in the USA for about 70 years‚ but leaving off the actual years. … I challenged the audience to identify the blight year (1970). Nobody could. … Try this on colleagues and students.

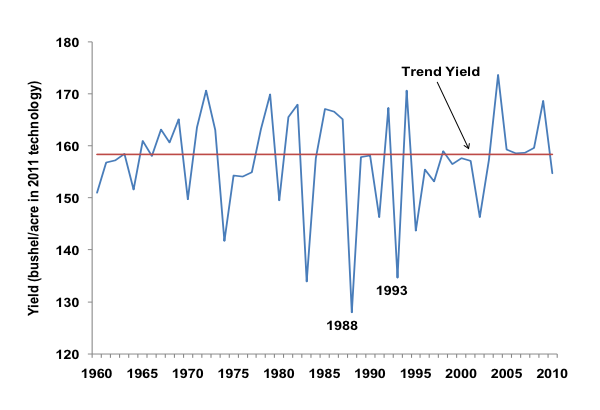

I did, and it is true, 1970 does not look all that extraordinary against the trend.

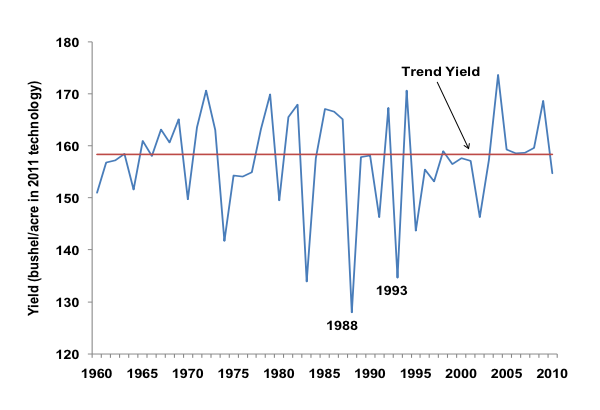

A more interesting graph is this one, in which the rising trend in average yield is removed from the actual yield each year.

Now 1970 is a little more visible, though I agree it still doesn’t look catastrophic. I mean, compare that with 1988 and 1993. There is one huge difference. In 1988 drought was widespread, while in 1993 floods devastated many farms and yields in the northwest corn belt. Weather in 1970 was just fine, thank you. Weather is clearly a very important factor in annual yields, and it interacts with pests and diseases in complex ways, but it seems pretty clear that the yield loss of 1970, while not as drastic as in other years, was certainly not the result of wayward weather.

The commenter asked “are we making too much of a fuss about the Leaf Blight”? I don’t think so, obviously, so I asked Professor Darrel Good, of the University of Illinois. He knows more about maize yields than almost anyone (and is responsible for the graphs above). He said:

I have not seen any specific analysis of 1970, but am pretty sure that the decline in corn yield was in fact attributed to the outbreak of southern corn leaf blight. Hard to quantify that impact relative to weather. It is a similar phenomenon as the aphid damage to the soybean crop of 2003. These rare events are not captured in our models.

In some respects, pests and diseases are as unpredictable as weather. In industrialized agriculture, genetic diversity within a crop is unlikely to provide much protection against the vagaries of weather. But genetic diversity definitely can protect against unpredictable pests and diseases, not just in maize, and not just against Southern Corn Blight.