- Ok here goes, there’s a week’s work of Nibbles we’ve got to catch up on.

- World running out of chocolate! Tell that to Cologne.

- Yeah well I prefer tea to cocoa.

- Greenpeace: “Smart breeding” will save us, not GMOs. Breeders: All breeding is smart.

- Guess the world’s biggest cash crop. Yeah, that one.

- Alas, it’s not included in the recent strategy for conserving medicinal plants. Not that it would need conserving.

- The domestication of the world’s biggest crop, period. Deconstructed. And if you want to drill down.

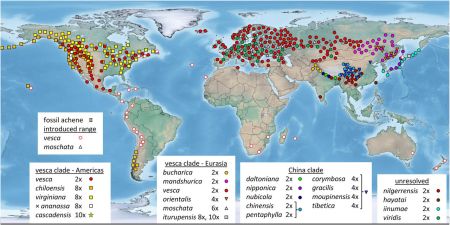

- And of the world’s biggest fruit.

- And of the world’s biggest pet.

- And of the world’s most difficult to eat vegetable.

- Root “vegetables” made simple. Because winter.

- And why you must eat your veggies, including the difficult ones.

- Videos on Kew’s monocot database and on the renovation of another famous herbarium.

- The real Johnny Appleseed.

- But you too can save seeds, just like Johnny.

- But don’t forget to safety duplicate, like CIP has done, at Embrapa.

- And this shows you what those seeds can look like.

- You don’t necessarily need seeds to save plants, though.

- Mapping fallen fruit. Because we can.

- Road trip!

- Boat trip!

- Selected Techniques in the Art of Agriculture. From French to Turkish to Arabic. One of many nifty agriculture-related resources in the World Digital Library.

- Oh yeah, the IUCN World Parks Congress has been on and its all over the intertubes. Including with neat visualizations, natch.

- How many of the species in the COMPADRE database of plant demography information are in protected areas? How many are crop wild relatives? I need an intern.

Brainfood: Basil resistance, Maize quality & drought, Benin sorghum, Swedish farm size, E European grapevives, Lebanese olives, Brazilian sheep, Sudanese cattle, Egyptian bean rhizobia, Barley origins, Intercropping

- Selecting basil genotypes with resistance against downy mildew. Only the exotic basils were any good. I will resist the temptation to make Fawlty Towers jokes.

- High grain quality accessions within a maize drought tolerant core collection. Not so much a core collection, rather a set of local and exotic drought-tolerant varieties put together in the former Yugoslavia. Some of which turn out to have decent quality too.

- Diversity, genetic erosion and farmer’s preference of sorghum varieties [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] in North-Eastern Benin. Climate change, poor soils and striga are the main problems, according to farmers, and none of their current varieties will help much, apparently, which is why they are disappearing.

- Effects of Farm Size and On-Farm Landscape Heterogeneity on Biodiversity—Case-Study of Twelve Farms in a Swedish Landscape. Small farms = heterogeneous farms = biodiversity-rich farms.

- Identification and characterization of grapevine genetic resources maintained in Eastern European colletions. SSR revealed that of 1098 mainly Vitis vinifera accessions, 997 were indigenous to E. Europe, 101 were Western European cultivars, hybrids, rootstocks and new crosses; the 997 accessions were actually 658 unique cultivars, 54% of which were maintained in the countries of origin only.

- Extent of the genetic diversity in Lebanese olive (Olea europaea L.) trees: a mixture of an ancient germplasm with recently introduced varieties. Three genetic groups around the Mediterranean, most Lebanese material typical of the eastern group; monumental trees similar to Cypriot varieties. In other news, there’s a World Olive Germplasm Bank of Marrakech.

- Application of microsatellite markers for breeding and genetic conservation of herds of Pantaneiro sheep. Evidence of inbreeding means a proper genetic management scheme needs to be designed and implemented.

- Historical demographic profiles and genetic variation of the East African Butana and Kenana indigenous dairy zebu cattle. The only indigenous African dairy breeds, apparently, but with distinct genetic histories despite their similar distribution in Sudan and dairy use.

- Phylogenetic multilocus sequence analysis of native rhizobia nodulating faba bean (Vicia faba L.) in Egypt. Three species, and evidence of horizontal gene movement among them.

- Transcriptome profiling reveals mosaic genomic origins of modern cultivated barley. The Fertile Crescent and Tibet.

- Improving intercropping: a synthesis of research in agronomy, plant physiology and ecology. You can breed for it. Among other things.

Brainfood: Filipino rice synonyms, Jatropha breeding, Polish oats, Amazonian peppers, Wild lentils, Indian pigeonpea, Russian peas, Pulse markers, Wild pollinators, Phenotyping platforms, Almonds & peaches, Cerrado roads, Arboreta conservation

- Multiplex SSR-PCR analysis of genetic diversity and redundancy in the Philippine rice (Oryza sativa L.) germplasm collection. 427 rice accessions in the national collection with similar names resolve to about 30 unique profiles. I think. The abstract is a little hard to follow, and that’s all I have access to.

- Quantitative genetic parameters of agronomic and quality traits in a global germplasm collection reveal excellent breeding perspectives for Jatropha curcas L. 375 genotypes, 7 locations and 3 years get you quite enough data to plan a decent breeding programme.

- Studies on genetic variation within old Polish cultivars of common oat. Forward into the past.

- Morphoagronomic peppers no gender pungent Capsicum spp. Amazonia. Actually nothing to do with gender. That’s a mis-translation of “genus,” if you can believe it. Paper basically says that Amazonian peppers are really variable, which is not as interesting as it might have been.

- Global Wild Annual Lens Collection: A Potential Resource for Lentil Genetic Base Broadening and Yield Enhancement. The core collection of wild annuals (which is actually a somewhat novel concept) comes mainly from Turkey and Syria, and it’s got diversity that’s not in the cultigen.

- Pigeon pea Genetic Resources and Its Utilization in India, Current Status and Future Prospects. Indian genebank evaluates the ICRISAT core and mini-core. Then does some mutation breeding :)

- Molecular genetic diversity of the pea (Pisum sativum L.) from the Vavilov Research Institute collection detected by the AFLP analysis. Molecular data does not correspond with subspecies nor ecogeographic groupings. Back to the drawing board.

- Characterization of microsatellite markers, their transferability to orphan legumes and use in determination of genetic diversity among chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) cultivars. Chickpea SSRs are ok for other, less studied, crops too.

- From research to action: enhancing crop yield through wild pollinators. Go wild.

- Integration of phenotyping and genetic platforms for a better understanding of wheat performance under drought. You really need managed environment facilities. Didn’t a paper in Brainfood last week say what you needed was a network of field sites? I guess you need both.

- Wild almonds gone wild: revisiting Darwin’s statement on the origin of peaches. He was not entirely wrong.

- The role of roadsides in conserving Cerrado plant diversity. 70% of species is not bad, I guess. No word on whether that includes wild peanuts, but I suspect yes.

- Do living ex situ collections capture the genetic variation of wild populations? A molecular analysis of two relict tree species, Zelkova abelica and Zelkova carpinifolia. Yes and no. But this is in botanic gardens and arboreta, what about seedbanks? The cerrado people want to know…

Speaking about Speaking of Food

This special issue, “Speaking of Food: Connecting basic and applied plant science,” aims to provide concrete examples of how a wide range of basic plant science, the types of scientific studies commonly published in AJB, are relevant for the future of food. This Special Issue was inspired by Elizabeth A. Kellogg’s 2012 Presidential Address to the Botanical Society of America, and resulted in part from a symposium and colloquium by the same name that took place at the 2013 Botany meetings in New Orleans, LA. The issue editors are grateful to the Botanical Society of America, the American Society of Plant Taxonomists, and the Torrey Botanical Society for support of this work.

Special issue of the American Journal of Botany, that is. Alas, only one of the papers, the one on strawberries, is open access, though.

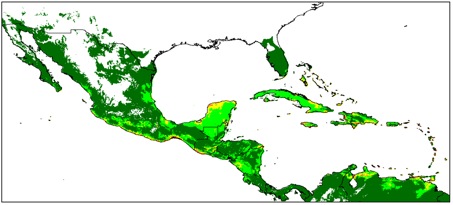

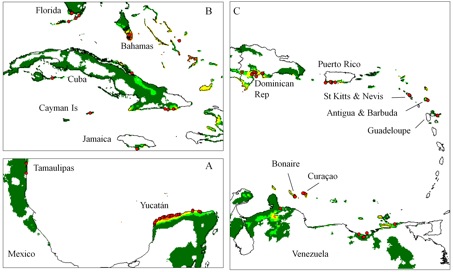

Comparing the niches of wild, feral and cultivated tetraploid cottons, Part 2

We’re trying something new for us this week. Dr Geo Coppens co-authored an interesting paper 1 recently which brings together a number of our concerns: domestication, diversity, crop wild relatives, spatial analysis… He’s written quite a long piece about his research, which we’ll publish here in three instalments. This is the second instalment. Here’s the first, in case you missed it.

To investigate the origin of cultivated cotton in the New World, we also had to define the distribution of the wild precursors, which meant distinguishing True Wild Cotton (TWC) populations from feral (secondarily wild) populations. We first defined five categories: (1) TWC populations, which were described as such by cotton experts with consistent ecological and/or morphological criteria; (2) wild/feral cottons, reported to grow in protected areas and/or forming relatively dense populations in secondary vegetation; (3) feral plants living in anthropogenic habitats (field and road margins); (4) cultivated perennial cottons; and (5) plants of indeterminate status. We then organized our extensive dataset of locality information from herbaria and genebanks in the same way as Russian nesting dolls.

Avoiding the problematic comparisons between consecutive categories, we first modelled G. hirsutum distribution based on the whole sample, then reducing the sample to ‘feral’+‘wild/feral’ + TWC , then to ‘wild/feral’+TWC, and finally to TWC alone. Thus, we could see that the distribution model (we used the Maxent software for niche modelling) was not significantly affected by the successive removals of specimens classified as indeterminate, cultivated, or feral. Only the model based on TWC populations diverged very clearly, their distribution being severely restricted to a few coastal habitats, in northern Yucatán and in the Caribbean, from Venezuela to Florida (Figures 1 and 2).

A principal component analysis on climatic parameters confirmed the absence of clear differences among the climatic niches of cultivated, feral, and ‘wild/feral’ populations, contrasting strikingly with that of TWC populations, restricted to the most arid coastal environments. The TWC habitat’s harsh conditions are quite certainly related to the fact that “Gossypium is xerophytic and that even its most mesophytic members are intolerant of competition, particularly in the seedling stage” (Hutchinson, 1954). The proximity to the sea plays a role itself, for these “extreme outpost plants” (Sauer, 1967). Indeed, as Fryxell (1979) puts it, wild tetraploid cottons are strand plants adapted to mobile shorelines, with impermeable seeds adapted to salt water diffusion. The instability of their habitat “is in itself highly stable” and very ancient, so “that the pioneers are simultaneously old residents”.

Extrapolating this TWC climatic model to South America and Polynesia points towards places where other wild representatives of tetraploid Gossypium species have been reported, which gives a strong example of niche conservatism. Thus, the distribution model has perfectly captured those conditions that are related to both biotic and abiotic constraints for the development of TWC populations.

To be continued…