- Pamela Akinyi Nyagilo wins prize for teaching Kenyan kids to grow indigenous greens. In 2007, but better late with the news than never.

- The Great War did for truffles?

- “Does a local food system truly enhance the integrity of a community, much less make the peasant the equal of a prince and eliminate greed?” And more. And more. And more. And…

- Crop art, and more. And more.

- Brassica seeds survive 40 years in a genebank with no loss of viability. Phew.

- “It seems that, while discount and low-end retailers face more difficulties selling organic products, specialised organic shops and high-end retailers continue to develop beyond expectations.”

- “As Andy Jarvis, an award-winning crop scientist, puts it: ‘When you look at the graph, under even small average heat rises, the line for maize just goes straight down.’ “

Too hot to fight

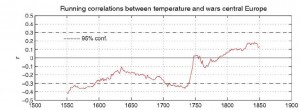

A short piece in the latest Economist describes a paper in Climate Change on the historical correlation between temperature and war. Up to about 1740-1750 colder years were also more warlike years, at least in Europe (the authors quote a paper that suggests there’s a similar correlation for China). This correlation is never particularly strong, though it is occasionally statistically significant, but then it breaks down entirely and shoots up into very slightly positive (though non-significant) territory.

Dr Tol and Dr Wagner suggest that in the more remote past the effects of cold weather on harvests led to supply shortages, and that these increased the likelihood of people fighting over food and the land needed to produce it. They argue that the reason the relationship between warfare and cold vanishes in the mid-18th century is that this is the moment when the industrial revolution began. Both agriculture and transport improved rapidly at this time. Systematic plant breeding, the introduction of new crops and new forms of crop rotation, and better irrigation increased the food supply. Improvements in roads and the large-scale construction of canals allowed food to be transported from areas of plenty to areas of scarcity.

Does this have implications for the future? Presumably, it implies that we need not worry about war breaking out in Europe due to climate change. Not so fast.

Just because cold, rather than heat, caused problems in Europe during the millennium that Dr Tol and Dr Wagner examined does not mean rising temperatures pose no threat. The lesson, rather, is that the way to minimise the likelihood of climate-induced conflict in the future is to continue the process of crop improvement (for example, by taking advantage of the potential of genetic engineering) so that heat- and drought-tolerant varieties are available; to make farmers aware of these new crops and encourage their use; and to promote free trade and non-agricultural economic development. That way people will have no cause to fight, and tyrants no excuse to stir them up.

There is no correlation in this dataset between precipitation and war, but that’s the one I’d be watching.

We are what we crop? – Part 2

Jacob van Etten continues our coffee-table conversation about whether crops determine everything.

All of this started off with Wittfogel’s Oriental despotism and how crops (rice) and cropping technologies (irrigation) give shape to whole societies. Jeremy mentioned Malcolm Gladwell, who argues in Outliers that Asians are good in math because they grow rice. Crops determine everything?

Wittfogel first. Some more recent opinions nuance the point about hierarchical rice societies. Yes, irrigation tends to give rise to more hierarchical societies. Dorian Fuller and Ling Qin write that the rise of water management in China in archaeological times went hand in hand with the development of social hierarchies. ((D.Q. Fuller & L. Qin. 2009. Water management and labour in the origins and dispersal of Asian rice. World Archaeology 41(1): 88-111.)) But rice irrigation is not as hierarchical as if Henry Ford had organized it. A lot of ‘participation’ goes on, as most water management ultimately relies on the efforts of both big and small players. Francesca Bray writes:

One of the main arguments that underlies such theories is that only a highly centralised state can mobilise sufficient capital and technical and administrative expertise to construct and run huge irrigation systems. It is certainly true that both Hindu and, later, Buddhist monarchs all over Southeast Asia saw it as part of their kingly role, an act of the highest religious merit, to donate generously from the royal treasuries to provide the necessary materials and funding. But kings were not the only instigators of such works. Temples, dignitaries, or even rich villagers often gave endowments to construct or maintain irrigation works on different scales.

Malcolm Gladwell actually argues something similar:

By the 14th and 15th centuries, landlords in central and southern China had a nearly hands-off role with their tenants, collecting only a fixed amount and letting farmers keep whatever yields they had left over. Farmers had a stake in their harvest, leading to greater diligence and success.

Celebrating rice

Have we already blogged these interviews with rice people? Check out, for example, Peter Jennings, IRRI’s first breeder, on the genesis of IR8, among other things.

It’s IRRI’s 50th anniversary next year, don’t forget. I guess the celebrations kick off with the 6th International Rice Genetics Symposium in Manila in November. And reach a climax at the 3rd International Rice Congress (IRC 2010) next November in Hanoi. Wonder if any spanners will materialize.

Nibbles: Livestock photos, Rice, Beer, Oca, Potatoes, Beer, Fermentation, Aquaculture, Chinese food, Citrus

- ILRI images are online.

- Rice farmers in Lao get an airing on Public Radio International.

- Tonto: expanding head banana beer.

- Rhizowen’s ongoing oca saga.

- “Intellectual property vital for agricultural innovation.” Er .. riiiiiiight.

- Instead of whinging, as we would, Laurent subverts the Blogger Bioblitz by including potatoes.

- The British National Hop Collection comes in useful. Hey, you had me at hops.

- Make better kimchi and the world will beat a path to your door.

- How many species of aquatic animals do you think farmers use in SE Asia?

- Labeling caviar.

- China’s food culture on the move.

- California’s oranges in big trouble.