- There are 227 bee species in New York City. Damn! But not enough known about the work they (and other pollinators) do in natural ecosystems, alas.

- Borlaug home to be National Historic Site?

- Archaeobotanist tackles Old World cotton.

- FAO suggests ways that small farmers can earn more. Various agrobiodiversity options.

- About 400 new mammal species discovered since 1993 (not 2005 as in the NY Times piece). Almost a 10% increase. Incredible. Who knew.

- But how many of them will give you nasty diseases?

- The caribou wont, I don’t think. And by the way, its recent decline is cyclical, so chill.

- Saving the American chestnut through sex. Via the new NWFP Digest.

- “The best thing IRRI can do for rice is to close down and give the seeds it has collected back to the farmers.” Yikes, easy, tiger! Via.

Old maps used to track down hops in Sweden

![]() I’ve done a fair amount of reading and thinking about the theory and practice of germplasm collecting in my time, but I don’t think I’ve ever come across an example similar to the one described in a recent paper in Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. ((Strese, E., Karsvall, O., & Tollin, C. (2009). Inventory methods for finding historically cultivated hop (Humulus lupulus L.) in Sweden. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. DOI: 10.1007/s10722-009-9464-9.))

I’ve done a fair amount of reading and thinking about the theory and practice of germplasm collecting in my time, but I don’t think I’ve ever come across an example similar to the one described in a recent paper in Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. ((Strese, E., Karsvall, O., & Tollin, C. (2009). Inventory methods for finding historically cultivated hop (Humulus lupulus L.) in Sweden. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. DOI: 10.1007/s10722-009-9464-9.))

In it, Swedish researchers describe how they took advantage of a couple of interesting quirks in the history of Sweden to devise what I think is a pretty novel strategy for sampling agrobiodiversity. They were interested in collecting germplasm of hops (Humulus lupulus) for a new genebank that’s under development. Now, the thing is that, although this crop is no longer grown in Sweden now, for 400 years from 1442 doing so was compulsory, in order to guarantee sufficient domestic production for beer-making. Very sensible, too.

Initially, all peasants were required to grow at least 40 hop poles. By 1483, the quantity was increased to 200 hop poles. The law was not formally repealed until 1860. As a result of this law, the plant has left several financial, fiscal and legal imprints on Swedish history.

The second historical curiosity about Sweden is that it boasts a unique set of some 12,000 large-scale maps dating back to the mid-17th century. Because of the hops law, hop gardens are actually marked on these maps in some detail (click to enlarge).

So the collectors used what they call a “history to plant” method to identify likely areas for collecting, using not only maps such as the one reproduced above, but also…

…medieval charters from the fifteenth century files of land belonging to the abbey of Vadstena, documents from the expeditions of Carl von Linné and his pupils from the eighteenth century and also documents from the breeding program in Svalöf from the beginning of the twentieth century.

And a pretty successful strategy it was too.

We found no hop plants at locations which were not indicated in the maps as hop gardens. Today living plants were possible to find in more then 33% of the total inventoried sites, indicated as hop gardens on large-scale maps.

As I say, I can’t think of another example of the use of historical maps to locate specific crops for sampling. No doubt the specific circumstances that made this possible in Sweden are not all that common around the world. Anyway, if you know of similar work, let me know. Always interested in keeping up to date with the latest in germplasm collecting.

Nibbles: Dogs squared, Afghanistan’s poppies, Rice at IRRI, Book on sapodilla chicle in Mexico, Opuntia, Trees

- DNA survey of African village dogs reveals as much diversity as in East Asian village dogs, undermines current ideas about where domestication took place.

- Fossil doubles age of dog domestication.

- “When children felt like buying candy, they ran into their father’s fields and returned with a few grams of opium folded inside a leaf.”

- “The rice, a traditional variety called kintoman, came from my grandfather’s farm. It had an inviting aroma, tasty, puffy and sweet. Unfortunately, it is rarely planted today.”

- “An era of synthetic gums ushered in the near death of their profession, and there are only a handful of men that still make a living by passing their days in the jungle collecting chicle latex…The generational changes in this boom-and-bust lifestyle reflect a pattern that has occurred with numerous extractive economies…”

- Morocco markets prickly pear cactus products.

- TreeAid says that sustainable agriculture depends on, well, trees.

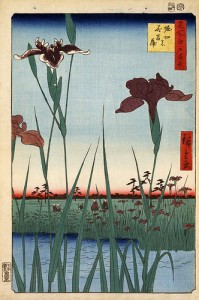

Iris in Japan and Tuscany

We went to the Hirishoge exhibition here in Rome some time ago, and very impressive it was too, but I don’t remember seeing this particular woodcut.

I’ve in fact only just come across it, on Flickr, where there is this fascinating commentary:

In the village of Horikiri in suburban Edo, gardeners grew a year-round variety of flowers and were particularly famous for the iris shown here, “hanashobu,” well suited to this swampy land. In this print Hiroshige has shown three, almost-life-size, detailed specimens of the nineteenth-century hanashobu hybrids and in the distance, sightseers from Edo are admiring the blossoms. In the 1870’s the cultivation of hanashobu had begun to spread rapidly in Europe and America and the developed into a booming export market for the gardeners of Horikiri. The Horikiri plantations began to wane in the 1920’s and eventually turned over to wartime food production. After the war, one of them was revived and is now a public park, particularly popular in May when the flowers are in bloom.

Multiple origins of agriculture debated

The point is that agriculture, like modern human behaviour, was not a one time great invention, but the product of social and environmental circumstances to which human groups with the same cognitive potential responded in parallel ways. The question in both cases is: what were the common denominators of those circumstances?

That’s from a post over at The Archaeobotanist which starts by talking about “modern human behaviour” rather than agriculture, but sees parallel processes at play in the origin of both. So, in the same way that “the cognitive architecture for modern behaviour was around but the innovations that we regard as ‘modern’ emerged when social and environmental circumstances demanded,” and this happened in different places at different times, so likewise the “cognitive architecture” for agriculture was widespread and there were therefore many “centres in which societies converged on agriculture,” with the concomitant “behavioural changes towards manipulation of the environment in favour of the reproduction of a few food species,” triggered by particular “social and environmental circumstances.”

Fair enough, but how is this new? There’s a comment on the post in which Paul Gepts makes this very point

…I am somewhat surprised that the issue of parallel inventions of agriculture is still an issue. The concept of centers of origin/domestication has been around for a century, thanks to Vavilov, Harlan, et al. … I must be missing something here, because for some time agriculture has been considered an example of multiple, independent inventions.

I’m looking forward to following this heavyweight exchange.