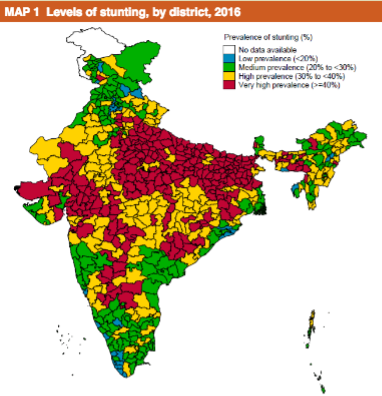

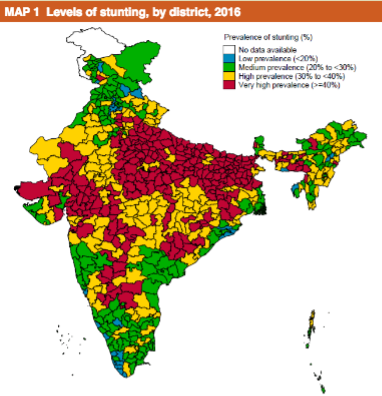

Is there a relationship between levels of stunting in Indian districts…

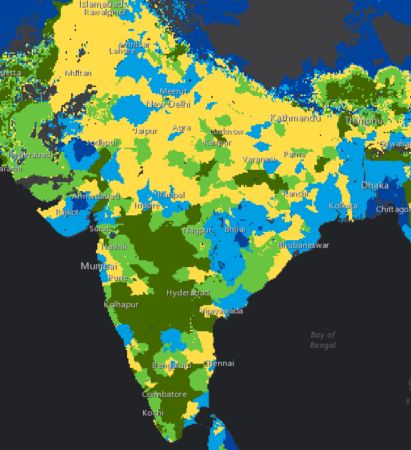

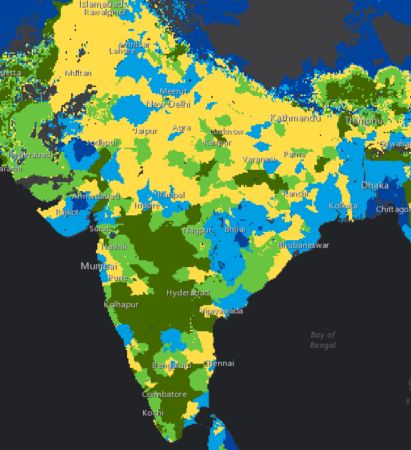

…and crop diversity in their farming systems (blue low, green high)?

I have no idea. But I think we should be told.

Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog

Agrobiodiversity is crops, livestock, foodways, microbes, pollinators, wild relatives …

Is there a relationship between levels of stunting in Indian districts…

…and crop diversity in their farming systems (blue low, green high)?

I have no idea. But I think we should be told.

“When countries change their trade policies to protect themselves against price falls, small farmers – particularly those in developing countries – tend to lose profits,” said Will Martin, senior research fellow at IFPRI. “This platform gives governments access to the most recent information available, so they can make informed decisions on food policy that avoid creating global price instability.”

“This platform” is Ag-Incentives, and it’s just been launched by IFPRI.

Policies that affect incentives for agricultural production, such as those that raise prices on domestic markets, can artificially distort the global market, which then undermine market opportunities for small farmers in the world. Ag-Incentives allows users to compare indicators, such as nominal rates of protection, across countries and years.

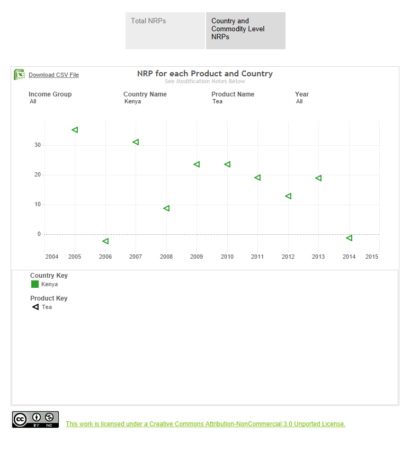

At the moment, it seems that it is only “nominal rates of protection” (NRP) that are being compared, across countries and years, but that will no doubt change as the platform evolves. What are NRPs?

…the price difference, expressed as a percentage, between the farm gate price received by producers and an undistorted reference price at the farm gate level.

The “undistorted price” being “generally taken to be the border price adjusted for transportation and marketing costs.”

If I understand this correctly, if NRP is negative, the commodity is being taxed, positive and it is being subsidised. This is the picture for tea in Kenya, as an example.

I’ll run it by the mother-in-law to see if she can make some sense of it, in particular what happened in 2006 and 2014.

FAO issued its report The future of food and agriculture: Trends and challenges a couple of months back, but I don’t think we mentioned it at the time, at least not in any detail.

Without a push to invest in and retool food systems, far too many people will still be hungry in 2030 — the year by which the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda has targeted the eradication of chronic food insecurity and malnutrition, the report warns.

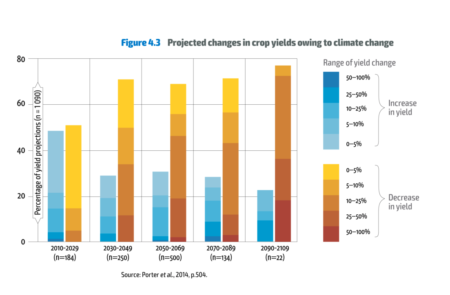

I come back to it now because of a useful digest that Ensia has just put out, summarizing the trends analyzed by the report in 12 handy graphs, of which this is perhaps the scariest.

What’s to be done? There’s much talk in the report about “innovative systems that protect and enhance the natural resource base, while increasing productivity” and a “transformative process towards ‘holistic’ approaches, such as agroecology, agro-forestry, climate-smart agriculture and conservation agriculture, which also build upon indigenous and traditional knowledge.” Nothing specifically on conserving crop diversity, however, though I suppose it could be implied in some of the above. There was this, though:

On the path to sustainable development, all countries are interdependent. One of the greatest challenges is achieving coherent, effective national and international governance, with clear development objectives and commitment to achieving them. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development embodies such a vision – one that goes beyond the divide of ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries. Sustainable development is a universal challenge and the collective responsibility for all countries, requiring fundamental changes in the way all societies produce and consume.

The International Treaty on PGRFA, although also not mentioned by name, is of course predicated on this very interdependence, and coincidentally there was a major development on that last week:

Switzerland proposes that a new paragraph should be added below the current list of crops contained in Annex I. The new paragraph should read as follows:

“In addition to the Food Crops and Forages listed above, and in furtherance of the objectives and scope of the International Treaty, the Multilateral System shall cover all other plant genetic resources for food and agriculture in accordance with Article 3 of the International Treaty.”

Switzerland requests the Secretary of the International Treaty to communicate this submission prior to the next ordinary session of the Governing Body to all Contracting Parties in accordance with Art. 23.2 of the International Treaty.

That should make for an interesting meeting of the Governing Body later this year, and put the talk of “collective responsibility” to the test.

Whizz-bang websites in support of data-dense papers seem to be all the rage.

Remember “Farming and the geography of nutrient production for human use: a transdisciplinary analysis,” published in the inaugural The Lancet Planetary Health a couple of weeks back? We included it in Brainfood, and linked to an article by Jess Fanzo which summarizes the main findings. This is probably the money quote:

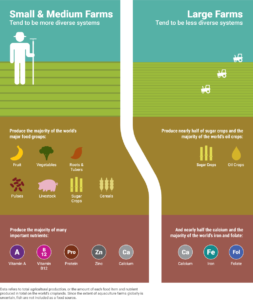

Both small and large farms play important roles in ensuring we have enough food that is diverse and nutrient-rich. While industrialised agriculture suggests domination of food systems, smallholder farms play a substantial role in maintaining the genetic diversity of our food supply, which results in both benefits and risk reductions against nutritional deficiencies, ecosystem degradation, and climate change. Herrero and colleagues argue that if we want to ensure that the global food supply remains diverse and generates a rich array of nutrients for human health, farm landscapes must also be diverse and serve multiple purposes.

Well, there’s also a graphics-rich website now, “Small Farms: Stewards of Global Nutrition?” The infographic at the left here puts it in the proverbial nutshell (click to embiggen).

Well, there’s also a graphics-rich website now, “Small Farms: Stewards of Global Nutrition?” The infographic at the left here puts it in the proverbial nutshell (click to embiggen).

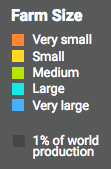

But what you really want to know is on what kinds of farms are grown those Canadian and Indian peas we talked about yesterday in connection with other fancy websites. Well, unfortunately, the data are only available for “pulses” here, but, perhaps unsurprisingly, those are grown mainly on large(ish) farms (blue) in North America, and small(ish) farms (orange) in South Asia. Each square is 1% of global production.

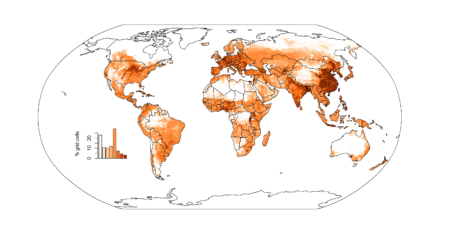

You can get similar breakdowns for different food groups (cereals, oils, etc.), and for a bunch of different nutrients: Calcium, Calories, Folate, Iron, Protein, Vitamin A, Vitamin B12, and Zinc. For all of these last you can also see global maps of nutritional yields, or “the number of people who can meet their nutritional needs from all of the crops, livestock, and fish grown in an area.” Here’s the one for Vitamin A.

You can get similar breakdowns for different food groups (cereals, oils, etc.), and for a bunch of different nutrients: Calcium, Calories, Folate, Iron, Protein, Vitamin A, Vitamin B12, and Zinc. For all of these last you can also see global maps of nutritional yields, or “the number of people who can meet their nutritional needs from all of the crops, livestock, and fish grown in an area.” Here’s the one for Vitamin A.

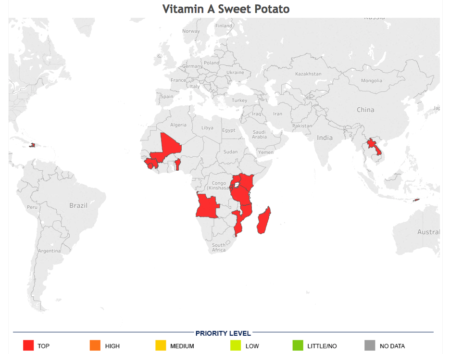

Which I’m sure will be of use in targeting the promotion of homegardening, say, or the roll-out of things like orange sweet potatoes. There is Biofortification Priority Index already, but only at a fairly coarse, country level. As far as I know, anyway.

Of course, those countries could always import sweet potatoes…