Congratulations to the GIS folks at CGIAR:

RTBMaps — a web-based GIS (Geographic Information Systems) tool to help planners visualize data and analyze options for using roots, tubers and bananas to improve food security, nutrition and income — has been selected for a Special Achievement in GIS (SAG) Award, presented today at the 2013 Esri International User Conference.

The thing is still in Beta, and there’s a lot more to come, both data and functionality:

RTBMaps is being launched with approximately 25 map layers, which are based on data for RTB crop distribution, indicators for poverty and food-security and some production constraints. However, the number of layers will grow as the GIS specialists at the research centers upload maps for additional pests and diseases, social indicators and other pertinent data. The RTB GIS team will also add applications for simple functions such as printing, or downloading maps for use in presentations. The team has also developed a priority setting application that allows users to weight the importance of different criteria — based on their own research, or consultations — and run analyses that result in unique maps.

Actually that priority-setting bit seems to be already there (more on this below). But for sure it will be nice to be able to share the results, which you can’t really do easily at the moment. And to import your own data, like localities of germplasm accessions, say. Which you also can’t do right now.

What can you do? Well, I couldn’t find much in the way of documentation, but playing around on the site suggests that basically what you can do is display those 25 layers in whatever combination you want on a map of the world. The layers include harvested area for potato, sweet potato, cassava, yam, banana and plantain, and a bunch of other variables: biotic (e.g. cassava mealybug climatic suitability), abiotic (e.g. length of growing period), socio-economic (e.g. % children underweight) and management (e.g. N fertilizer application). Each layer comes with a little pop-up which gives you the legend and lets you change its transparency, so that you could, for example, display cassava area together with climatic suitability for the cassava mealybug, and figure out where that pest is likely to do the most harm. You’d have to do that by eye, mind you, by tweaking the transparency settings. Tricky, and not hugely satisfying, but possible.

No, but wait. There’s a “Tools” tab: always a good sign. That allows you to run something called Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, or MCDA. I think that’s the priority-setting application mentioned above. The way it works is that you choose a crop, then choose from a list of six criteria, and I quote: reduce poverty, food insecurity, nutrition and health, sustainability of natural resources, increase productivity and profit , and increase market conditions. So I chose cassava as my crop, and reducing poverty plus nutrition and health as my criteria. You then give a weight to each criterion, 50% each in my case.

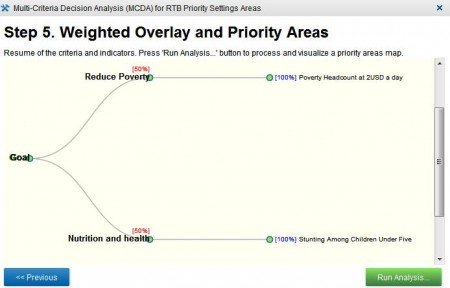

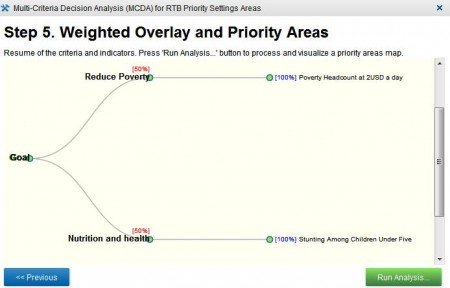

Ok, so the next step is to choose indicators for each of your criteria. You’re presented with the same list of 12 indicators for each of the criteria, the first six simply the harvested areas for all the crops in the system , the others the following, and again I quote: stunting among children under 5, poverty headcount at USD2 a day, absolute number of poors (sic.) at USD2 a day, irrigation areas, failed season, and accessibility. So I chose the poverty headcount as my indicator for reducing poverty, and stunting as my indicator for nutrition and health. If I had chosen more than one indicator for any of my criteria, I would have been able to give each a weight. But frankly, I was confused enough. Fortunately, I got a little reminder of what I’d done:

So I clicked on “Run analysis…”, though more in hope than expectation…

I am absolutely convinced that it is a huge technical achievement that the resulting analysis took only about 30 seconds. As my friend Glenn Hyman, one of the people involved, said in the press release already quoted above:

…RTBMaps is the most comprehensive and collaborative GIS web-mapping project to be undertaken within the CGIAR system to date. He noted that the cloud technology that it is based on has only become available in recent years.

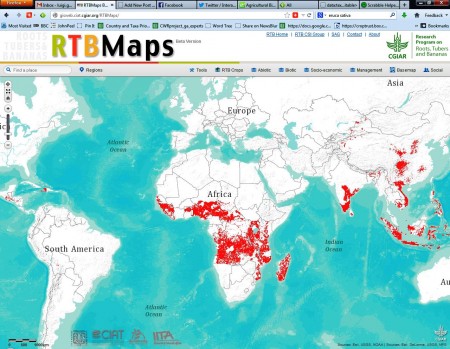

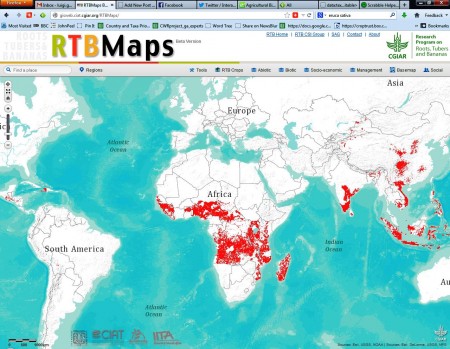

I have no doubt all of that is true, and admirable. However, I also have to admit that I have little idea what the map produced by this cloud-technological, and most comprehensive and collaborative, web-mapping project actually means. Here is that map:

Let me hazard a guess. What I think the map may mean is that if your goal is to reduce poverty and improve nutrition and health, in equal measure, and you want to do this via cassava, the areas in red are…what? The places where you would have the best chance of succeeding? The places where you’re going to have the biggest impact? The places where you should go on holiday?

I should have gone to the workshop, I guess. Maybe if I had, I’d be able to understand the whole thing more, and explain it better. And it is still in Beta, so there’s stuff in the pipeline, including documentation, no doubt. The idea of providing diverse maps online, and allowing users to combine them in fancy ways in support of decision-making, is certainly a great one. I really hope to see the promise of RTBMaps fulfilled.