You know that paper entitled Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being, that we included in Brainfood a couple of weeks back?. The money quote was: “The indirect effects of climate change on food webs are also expected to compound the direct effects on crops.” Ok, well, you don’t have to read it. All you have to do is watch a 1.5 minute video.

Brainfood: Slow Food, Runner bean diversity, Bamboo diversity, Istrian grapes, Smelly cheeses, Wild pseudocereals, Diversity & phenology, VAM diversity, Oases apocalypse, Wild wheat physiology, PepperHub, Bactrian camel diversity, Swiss livestock, CWR conservation, Tree database

- Developing radically-new meanings through the collaboration with radical circles: Slow Food as a platform for envisioning innovative meanings. Companies should collaborate with radicals. Presumably in order to turn them. #resist

- Unraveling agronomic and genetic aspects of runner bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.). At least we know what we don’t know.

- Total leaf crude protein, amino acid composition and elemental content in the USDA-ARS bamboo germplasm collections. If you want to use bamboo as feed, you need to choose among the 100-odd species very carefully.

- The Gene Collection of Autochthonous Wine Grape Varieties at the Institute as a Contribution to the Sustainable Development of Wine Growing and Viticulture in Istria. 3591 seems a hell of a lot, but wow.

- Phage Biodiversity in Artisanal Cheese Wheys Reflects the Complexity of the Fermentation Process. Modern methods kill a lot of phages.

- Setting conservation priorities for Argentina’s pseudocereal crop wild relatives. Go north, young CWR researcher!

- Flowering phenology shifts in response to biodiversity loss. Experimentally decreasing diversity in a California grassland advanced phenology.

- Activity, diversity and function of arbuscular mycorrhizae vary with changes in agricultural management intensity. No-till helps VAM, helps soils.

- Oases in Southern Tunisia: The End or the Renewal of a Clever Human Invention? I’m not hopeful.

- Physiological responses to drought stress in wild relatives of wheat: implications for wheat improvement. 4 species show promise.

- PepperHub, a Pepper Informatics Hub for the chilli pepper research community. Hot off the presses.

- Molecular diversity and phylogenetic analysis of domestic and wild Bactrian camel populations based on the mitochondrial ATP8 and ATP6 genes. The wild species is not the ancestor, and the domesticated species is a geographic mess.

- GenMon-CH: a Web-GIS application for the monitoring of Farm Animal Genetic Resources (FAnGR) in Switzerland. Upload data on your herd or flock, end up with a map of where the breed is most endangered.

- Stealing into the wild: conservation science, plant breeding and the makings of new seed enclosures. Ouch!

- GlobalTreeSearch – the first complete global database of tree species and country distributions. 60,065, about 10% crop wild relatives.

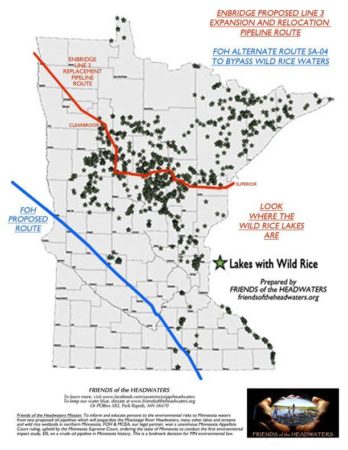

Faux wild rice in peril

I’m not saying it’s the most important thing about it, but that oil pipeline that is planned for Minnesota will go straight through lakes which are sacred to the local Native American peoples, and which generate about 50% of the world’s annual harvest of handpicked wild rice (which is Zizania, not Oryza, but still).

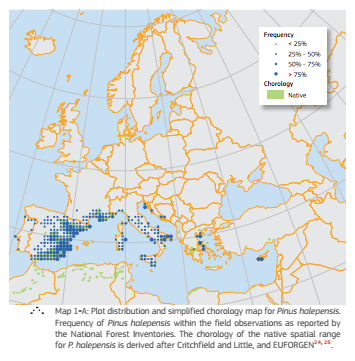

Seeing the wood and the trees

The day after the Global Tree Assessment is published by BGCI, which revealed there are about 60,000 tree species in the world, is also a good time to link again to the wonderful European Atlas of Forest Tree Species. Now all we need is the same thing for Brazil, which has about 9,000 of those 60,000. BTW, a very quick check suggests that about 1% of trees are crop wild relatives, globally. More on this later.

The day after the Global Tree Assessment is published by BGCI, which revealed there are about 60,000 tree species in the world, is also a good time to link again to the wonderful European Atlas of Forest Tree Species. Now all we need is the same thing for Brazil, which has about 9,000 of those 60,000. BTW, a very quick check suggests that about 1% of trees are crop wild relatives, globally. More on this later.

Are you a new or a traditional conservationist?

Although discussions about the aims and methods of conservation probably date back as far as conservation itself, the ‘new conservation’ debate as such was sparked by Kareiva and Marvier’s 2012 article entitled What is conservation science?

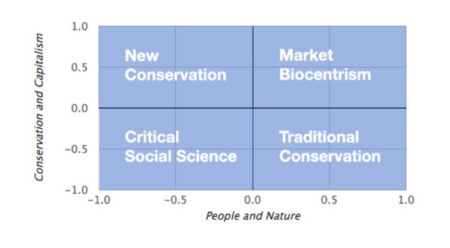

Two prominent positions have emerged in this debate, that of Kareiva and Marvier, which we label ‘new conservation’ (top-left quadrant of the figure below), and a strongly opposed viewpoint that we label ‘traditional conservation’ (bottom-right quadrant).

These positions can be clearly distinguished by their views on nature and people in conservation on the one hand, and on the role of corporations and capital in conservation on the other hand (the two axes in the figure).

Want to know which quadrant you fall into? Take the survey.

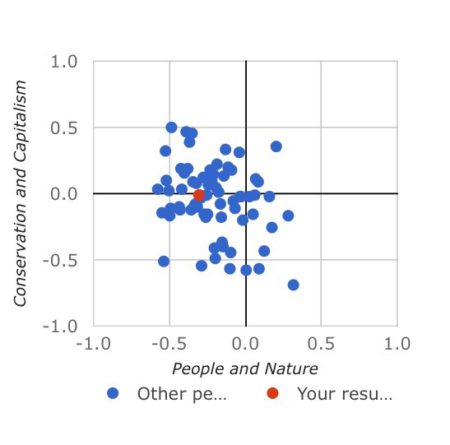

I did, and this is what I got.

Which basically means I’m wishy-washily neutral (agnostic? conflicted?) on the role of the private sector, and apparently think conservation needs to show some benefit for people, in particular poor people. And in that it seems I’m pretty near the centroid of opinion, at least when it comes to the last 100 people who took the survey. Of course, this is for biodiversity conservation. I wonder if the results would be different for conservation of agricultural biodiversity.