![]() So you’re telling me 1 that sixteenth century Italian gardeners selected long, thin squashes from among those brought back to Europe from the Americas (actually two different places in the Americas) in conscious imitation of the bottle gourds they had used for centuries? And somehow kept them separate from other cucurbits so that they bred true? And that the word zucchini shifted to the former from a particular, Tuscan form of the latter in the 1840s? Which is 50 years earlier than originally thought? Oh boy, I think I’m going to need some help navigating through this. Fortunately, Jeremy had the bright idea to ask the authors for directions.

So you’re telling me 1 that sixteenth century Italian gardeners selected long, thin squashes from among those brought back to Europe from the Americas (actually two different places in the Americas) in conscious imitation of the bottle gourds they had used for centuries? And somehow kept them separate from other cucurbits so that they bred true? And that the word zucchini shifted to the former from a particular, Tuscan form of the latter in the 1840s? Which is 50 years earlier than originally thought? Oh boy, I think I’m going to need some help navigating through this. Fortunately, Jeremy had the bright idea to ask the authors for directions.

Home is where conservation begins

Thanks to Jade Philips (see her on fieldwork below) and Åsmund Asdal, two of the authors, for contributing this post on their recent paper on the conservation of crop wild relatives in Norway.

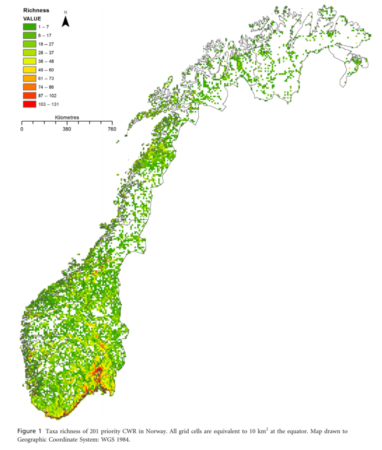

![]() Norway may be an unlikely spot in which to look for agrobiodiversity, but seek and ye shall find. A recent paper discusses the development and implementation of an in situ and ex situ conservation strategy for priority crop wild relatives (CWR) in the country. 2 Some 204 taxa were prioritized, which included forage species, berries, vegetables and herbs. Distribution data collected from GBIF and species distribution modelling software including MaxEnt and the CAPFITOGEN tools were used to identify conservation priorities.

Norway may be an unlikely spot in which to look for agrobiodiversity, but seek and ye shall find. A recent paper discusses the development and implementation of an in situ and ex situ conservation strategy for priority crop wild relatives (CWR) in the country. 2 Some 204 taxa were prioritized, which included forage species, berries, vegetables and herbs. Distribution data collected from GBIF and species distribution modelling software including MaxEnt and the CAPFITOGEN tools were used to identify conservation priorities.

A proposal was made for a network of in situ genetic reserves throughout Norway to help capture the genetic diversity of priority CWR and allow them to evolve along with environmental changes. Some 10% of priority species do not seem to be found in existing protected areas.

A proposal was made for a network of in situ genetic reserves throughout Norway to help capture the genetic diversity of priority CWR and allow them to evolve along with environmental changes. Some 10% of priority species do not seem to be found in existing protected areas.

Complementary ex situ priorities were also set out in the paper to ensure the full range of ecogeographic diversity across Norway, and hence genetic diversity, was captured within genebanks and therefore easily available for plant pre-breeders and breeders to utilise. Some 177 species have no ex situ collections at all. The priority CWR identified and the methodology used within Norway are applicable both in other countries and internationally. We hope that now the scientific basis for the conservation of these vital resources within Norway has been identified, integration of these recommendations into current conservation plans will begin. This will take us one step closer to the systematic global protection and use of our wild agrobiodiversity, a need which is growing increasingly urgent each day.

Brainfood: Organic penalty, Rye gaps, Sustainable diet indicators, Wheat evolution

- Commercial Crop Yields Reveal Strengths and Weaknesses for Organic Agriculture in the United States. The headline will be that organic yield is 80% of conventional, but the results are far more nuanced than that suggests.

- Genetic Distinctiveness of Rye In situ Accessions from Portugal Unveils a New Hotspot of Unexplored Genetic Resources. More collecting needed.

- A Consensus Proposal for Nutritional Indicators to Assess the Sustainability of a Healthy Diet: The Mediterranean Diet as a Case Study. 13 indicators of sustainability described, from “Vegetable/animal protein consumption ratios” to “Diet-related morbidity/mortality statistics.”

- Reconciling the evolutionary origin of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). One slightly changed ancestral subgenome, one much-changed ancestral subgenome, and one weird hybrid subgenome involving the previous two plus another. Basically, we were insanely lucky to get wheat.

A genebank in need

Our vault, where we store over 20,000 varieties of rare and heirloom seeds is critical to that mission. And the vault is failing. It has a crack in the floor, which could potentially lead to unstable temperatures and structural instability.

Do consider helping Seed Savers Exchange. They do great work. As, indeed, do thousands of seed savers around the world.

Damaging dichotomies

To mark the IUCN World Conservation Congress, which starts tomorrow with a visit by President Obama, I have a post over at the work blog arguing (well, implying) that the biodiversity conservation community has got itself into a tangle dividing its work into in situ and ex situ 3. When will we see genebanks, including Svalbard (about which there’s a new book out, incidentally), as an integral part of biodiversity conservation, rather than a reluctantly tolerated add-on? Answers on a postcard, please.