A recent paper reported on the discovery of a bit of the barley genome where an allele from the wild relative, when homozygous, confers a 30% yield advantage over a popular German variety under saline conditions. 1 That of course is very interesting in its own right, but I want here to delve a bit into the methods, rather than the results.

The main tool used by the researchers at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia was a “nested association mapping population” of barley called HEB-25. That stands for ‘Halle Exotic Barley 25’. The Halle bit refers to the site of the German plant breeding institute where the population was made. Following the trail of references from the KAST paper takes you to a 2015 paper which describes the history of HEB-25:

The population results from initial crosses between the spring barley elite cultivar Barke (Hordeum vulgare ssp. vulgare, Hv) and 25 highly divergent exotic barley accessions, contributing an ideal instrument to study biodiversity. The exotic donors comprise 24 wild barley accessions of H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum (Hsp), the progenitor of domesticated barley, and one Tibetian H. vulgare ssp. agriocrithon (Hag) accession. Barke was selected since it was also used as a parent of a barley high-resolution mapping population and as a genetic stock for mutation screening.

To generate HB-25, F1 plants between Barke and those 25 diverse barley samples were backcrossed to Barke and then selfed three times to make a total of 1,420 lines, each with a mainly Barke background, but different bits of genome from the 25 other samples. The researchers in Saudi Arabia then “simply” identified which bits of whose genome are associated with increased tolerance to salinity.

A lot of work. But we can take the story even further back. How were those 25 diverse barleys chosen? Again, following the trail of references takes you to a 1999 paper:

The exotic donors were selected from Badr et al. to represent a substantial part of the genetic diversity that is present across the Fertile Crescent, where barley domestication occurred.

Badr et al. (1999) was a very academic study of the origins of barley using molecular markers that would now be sneered at, but were all the rage back then:

The monophyletic nature of barley domestication is demonstrated based on allelic frequencies at 400 AFLP polymorphic loci studied in 317 wild and 57 cultivated lines.

So there you have it, 17 years from basic work on the geographic distribution and history of wild barley diversity to the identification of a particular, tiny bit of that diversity that confers a yield advantage to the crop under salinity stress. It would probably be a lot faster now, but you can see why using crop wild relatives in breeding is a bit of an acquired taste. And also that basic diversity research is needed for successful applied breeding.

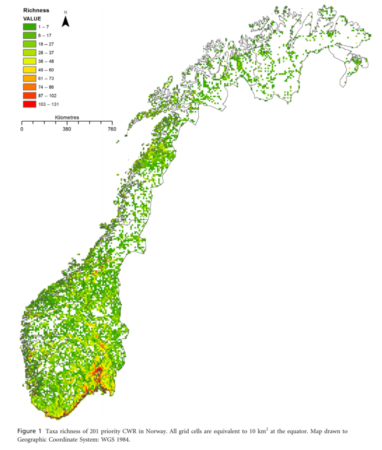

A proposal was made for a network of in situ genetic reserves throughout Norway to help capture the genetic diversity of priority CWR and allow them to evolve along with environmental changes. Some 10% of priority species do not seem to be found in existing protected areas.

A proposal was made for a network of in situ genetic reserves throughout Norway to help capture the genetic diversity of priority CWR and allow them to evolve along with environmental changes. Some 10% of priority species do not seem to be found in existing protected areas.