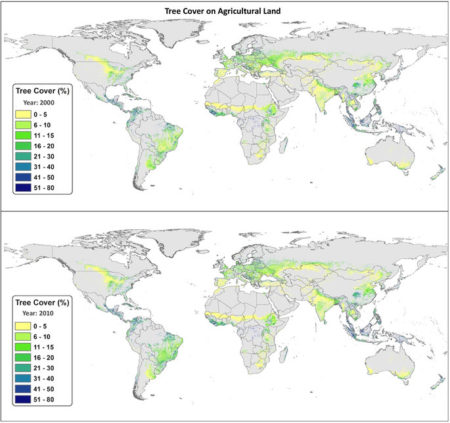

I’ve been looking for an excuse to play around with the Database of Places, Language, Culture and Environment (D-PLACE), which “contains cultural, linguistic, environmental and geographic information for over 1400 human ‘societies’”. It finally arrived today, in the form of a monumental study of carbon sequestration on farmland in Nature. The authors used remote sensing and fancy spatial modelling to work out the amount of tree cover, and hence the levels of biomass carbon, on agricultural land around the world. This is the global map they got for % tree cover in 2000 and 2010.

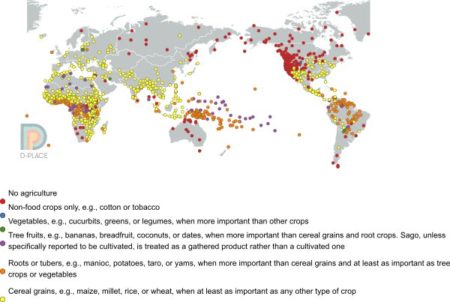

I was curious to see whether one could predict the areas of highest tree cover (or highest biomass C) from the much coarser data on agriculture that D-PLACE brings together from ethnographic studies. This is what the distribution of “major crop type” looks like, from D-PLACE.

So the answer is no, I guess. It’s difficult to see any association between the amount of trees on farms and the main types of crops grown there, at least just by eyeballing the maps. There may be a hint of a preference for roots and tubers, but nothing really jumps out. I’ll keep playing though, there’s a whole range of cultural and ecological variables you can tweak.