- Using in situ management to conserve biodiversity under climate change. It can probably be done, but more empirical evidence of long-term effects is needed.

- Rare phenotypes in domestic animals: unique resources for multiple applications. Difficult to conserve, but worth doing, and biotech will help.

- Patterns of SSR variation in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seeds under ex situ genebank storage and accelerated ageing. SSRs don’t help figuring out viability loss.

- Germplasm banking of the giant kelp: Our biological insurance in a changing environment. Chileans conserve female and male gametophytes in low light, at 10 °C, in Provasoli media.

- Authentication of “mono-breed” pork products: Identification of a coat colour gene marker in Cinta Senese pigs useful to this purpose. This particular pig breed can be easily and accurately identified.

- Microsatellite and Mitochondrial Diversity Analysis of Native Pigs of Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot. Native Indian pigs closer to Chinese than European.

- Yam (Dioscorea spp.) responses to the environmental variability in the Guinea Sudan zone of Benin. Different varieties respond differently to different conditions, at least as regards yield.

- Diversity and genetic structure of cassava landraces and their wild relatives (Manihot spp.) in Colombia revealed by simple sequence repeats. Lots of geneflow.

- Current availability of seed material of enset (Ensete ventricosum, Musaceae) and its Sub-Saharan wild relatives. Not much.

- Monitoring adventitious presence of transgenes in ex situ okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) collections conserved in genebank: a case study. None found.

Not so sweet potatoes

And speaking of Facebook, which has somehow become the go-to place for fun agrobiodiversity stuff, get a load of this recent photo of “bush potato” from the Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation.

Impressive, isn’t it? It’s Ipomoea costata, according to a commenter. And it reminded me of another recent Facebook post of a sweet potato wild relative, Ipomoea bolusiana, this time from southern Africa.

Thinking back to our earlier post today on domesticating promising wild plants, I wonder if anyone has actually tasted these tubers?

Underutilized for a reason?

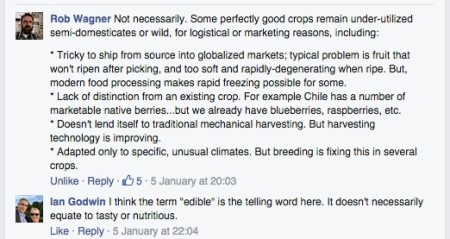

Over on Facebook, I half-facetiously commented on a piece entitled Global food shortage? How advanced breeding could domesticate 50,000 wild, edible plants by saying that if any of those plants were really any good, they would probably have been domesticated already. I’m not entirely sure I believe that, but I liked Rob Wagner’s and Ian Godwin’s reactions, and I hope they don’t mind me sharing them here. There’s more to adding a new crop to our agricultural menu than fancy breeding.

The most valuable fruit introduction yet

The Sacramento Bee has a nice piece by David Boulé 1 about the history of the ‘Washington’ Navel Orange in California, the world’s second most common orange variety (after ‘Valencia’).

Navel oranges have been known in Spain and Portugal for centuries. They made their way from there to Brazil, where, in Bahia, a seedless and easy-to-peel variety of great taste and color was discovered. It was probably a sport (mutant) from the Portuguese variety ‘Umbigo’, which is said to be described in the Histoire naturelle des orangers by Risso and Poiteau (you can get your own copy). I could not find it in that book, but I did enjoy Poiteau’s botanical drawings, like this one 2:

From Bahia the tasty navel went to Australia in 1824 and to Florida 3 in 1835, and from Australia to California. But the introduction that led to adoption of the name ‘Washington’ and to its commercialization in California and around the world occurred in 1870, when William O. Saunders of the USDA received twelve trees from Bahia (twigs in an earlier shipment had been dead on arrival). They were planted in a greenhouse in Washington D.C. and propagated for distribution 4.

On 10 December 1873, Eliza Tibbets of Riverside, southern California, traveled by buckboard to Los Angeles to pick up two of these trees, delivered by stagecoach from San Francisco 5. Their fruits won first price at a citrus fair in 1879, and the ‘Washington’ navel spread rapidly after that — there was a citrus gold rush going on after the recent completion of the transcontinental railroad, which allowed selling to markets back east. Oranges were commonly propagated by seed in California, but the seedless ‘Washington’ had to be grafted. The Tibbets sold cuttings at a dollar each, earning as much as $20,000 a year.

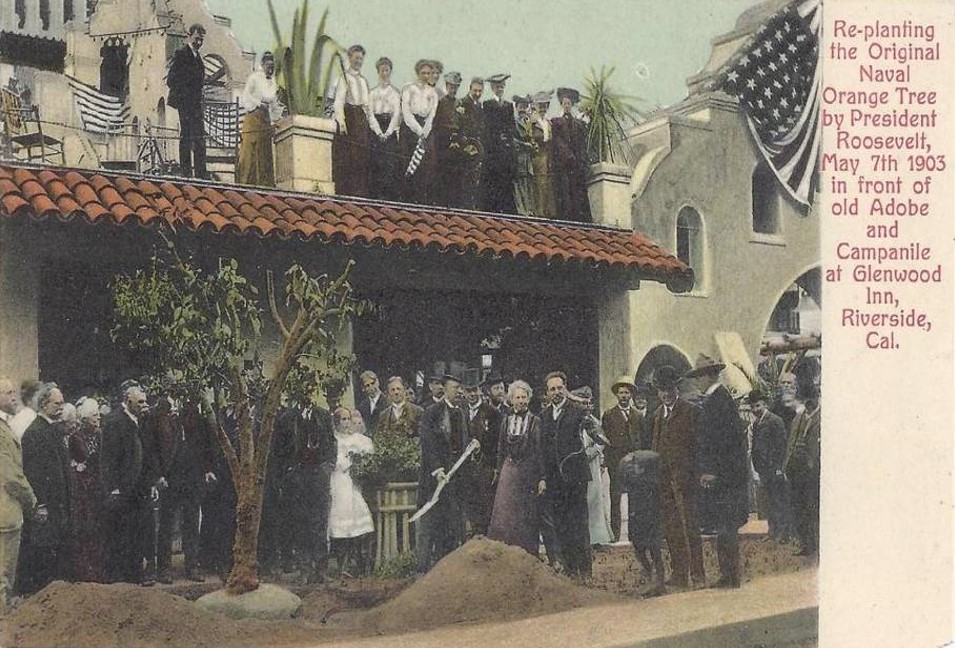

In 1903, one of the original trees was transplanted to a location in front of the Glenwood Hotel in central Riverside, with president Roosevelt shovelling some of the dirt. 6

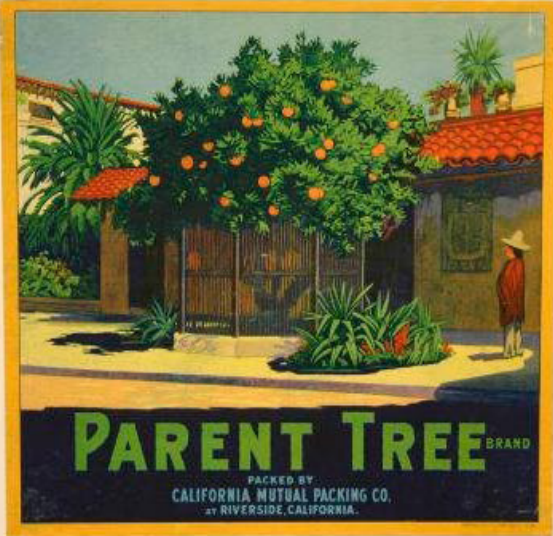

That must have been about here (the name of the hotel was changed to Mission Inn). Alas, the tree died after a couple of years. But it was there long enough to be used in marketing:

The other ‘parent tree’ was planted a couple of miles south of the Glennwood Inn, in Low Park. It is still there, see for yourself, about 145 years old, despite its dire state 50 years ago:

for some years past it has been declining in vigor, and in 1967 seemed unlikely to survive much longer.

The tree is a ‘California historical landmark’ and has this plaque in front of it:

which states that, as of 1920, this was the

most valuable fruit introduction yet made by the USDA.

Was that a fair claim back then? And if so, is it still true? There is some economic analysis here and here.

Riverside does not boast only that tree, it also has the California Citrus State Historic Park. And after you visit that, drive east to the Coachella Valley to see the dates that were introduced a few decades later. 7

Featured: MGIS

Max Ruas of Bioversity says they’re still working on the MGIS ordering system:

The availability of ITC material is only visible once you are logged into MGIS. If logged, then, for ITC accessions available for distribution, a tiny basket appears on top right corner of the passport data. I agree it is not perfect and we will continue to improve the friendliness of the web site in the next iterations, in addition of new features in preparation such as cross reference.

Looking forward to the new iteration. In the meantime, when can we expect MGIS data in Genesys?