A short Smithsonian.com piece by Barry Estabrook does a really outstanding job of describing — no, explaining — the conservation and use of crop wild relatives to a lay audience. It’s all there. The value to crop breeders of genes from wild relatives. The history of germplasm exploration, and how it has resulted in the establishment of large collections. The need for, and urgency of, further collecting. The use of information from genebanks to guide future exploration. The challenges that such work faces, including on the policy side. And the euphoria that it can generate when you do overcome those challenges. All in a couple of pages, using a single wild species as an example. And if, once you finish reading the story, you want to know more about what Estabrook was chasing in Peru, it’s (probably) this.

Brainfood: Pepper tree conservation, Buckwheat diversity, Seed drying, Grape database, Livestock improvement, Soil bacterial diversity, TLB in Nigeria, Humans & diversity double, Faidherbia @ICRAF

- Genetic structure and internal gene flow in populations of Schinus molle (Anacardiaceae) in the Brazilian Pampa. Try to keep what forest patches remain. And link them up somehow.

- Genetic Diversity of Buckwheat Cultivars (Fagopyrum tartaricum Gaertn.) Assessed with SSR Markers Developed from Genome Survey Sequences. Two groups, overlapping in Qinghai, China.

- Increases in the longevity of desiccation-phase developing rice seeds: response to high-temperature drying depends on harvest moisture content. Genebanks may have it wrong for seeds of rice (and perhaps other tropical species) harvested while still metabolically active: these you can dry at higher temperatures than is the norm.

- Vitis International Variety Catalogue (VIVC): A cultivar database referenced by genetic profiles and morphology. Now with added microsatellites.

- Options for enhancing efficiency and effectiveness of research capacity for livestock genetics in, and for, sub-Saharan Africa. Embed in wider rural development, collaborate, and share data. Could apply to more than just livestock improvement.

- Mapping and validating predictions of bacterial biodiversity using European and national scale datasets. It’s the pH.

- Agricultural Extension Roles towards Adapting to the Effects of Taro Leaf Blight (Tlb) Disease in Nsukka Agricultural Zone, Enugu State. Basically, extensionists haven’t done a thing.

- Anthropogenic drivers of plant diversity: perspective on land use change in a dynamic cultural landscape. Abandoning farmland is not good for biodiversity.

- Agricultural landscapes and biodiversity conservation: a case study in Sicily (Italy). Ahem. Abandoning farmland is not good for biodiversity.

- Genetic diversity of Faidherbia albida (Del.) A. Chev accessions held at the World Agroforestry Centre. It’s not enough.

Talking about Talking Biotech

Frankly, something called Talking Biotech would not normally get a second look from me. Too narrow. Too nerdy. Probably too preachy. But I’d be wrong in the case of Dr Kevin Folta’s podcast. It is nerdy, but in a good way; and it isn’t preachy (well, mostly not too preachy). And, despite it’s title, it’s not just about biotech. There tends to be a section in each hour-long weekly episode, usually towards the end, where an expert talks to Dr Folta about how a crop evolved, and how it is being improved: recent episodes include Dr David Spooner on the potato, Prof. Pat Heslop-Harrison on the banana, and Drs Shelby Ellison and Philipp Simon on the carrot. You can subscribe in iTunes, where you can also leave a review.

Early agriculture in the Old and New Worlds

Last week saw the publication of a couple of papers about early agriculture in two very different regions which will probably have people talking for quite a while. From Snir et al. 1 came a study of pre-Neolithic cultivation in the Near East. And from the other side of the world, there was the latest in the controversy over the extent of Amazonian agriculture from Clement et al. 2.

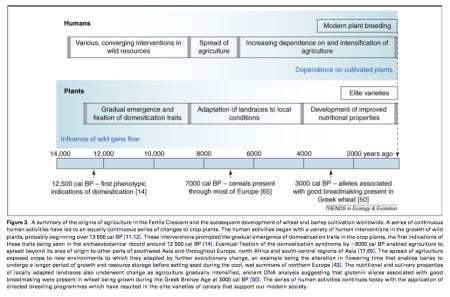

Yes, I did say pre-Neolithic. The key finding of the archaeological work described by the first paper is that 23,000 years ago, or over 11 millennia before the putative start of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent, hunter-gatherers along the Sea of Galilee in what is now Israel maintained little — and, crucially, weedy — fields of cereals. The archaeobotanists found remains of both the weeds and the cereals at a site called Ohalo II, as well as of sickles, and the cereals were not entirely “wild”, as the key domestication indicator of a non-brittle rachis was much more common than it should have been. To see what this means, have a look at this diagram from a fairly recent paper on agricultural origins in the region. 3

Those “first phenotypic indications of domestication”, dated at 12,500 years ago, need to be pushed quite a bit leftwards on that timeline now, off the edge in fact. A non-shattering rachis, it seems, was quite a quick trick for wild grasses to learn. But the process by which they acquired all the other traits that made them “domesticated” was very protracted and stop-start.

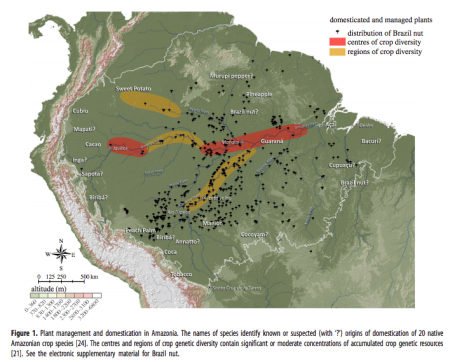

Zoom over to Amazonia, and the transition to farming took place much later, probably around 4,000 years ago, according to the other paper published last week. But it was just as significant as in the much better-known “cradle of agriculture” in the Fertile Crescent, with perhaps 80 species showing evidence of some domestication. The difference, of course, is that Amazonian agriculture was based on trees, rather than annual grasses and legumes.

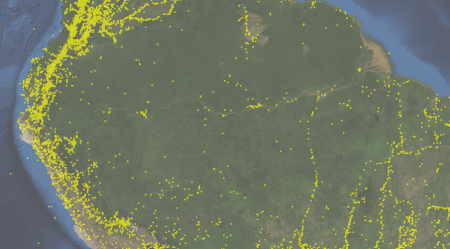

According to the authors, parts of the Amazon basin, in particular those now showing evidence of earthworks and dark, anthropogenic soils, were just as much managed landscapes by the time of European contact as the places those Europeans came from. But compare our collections of crop diversity from the Amazon basin (courtesy of Genesys, which admittedly does not yet include Brazilian genebanks)…

with what we have from the Near East…

If we want to know more about how the domestication process and transition to agriculture differed in the Amazon and the Fertile Crescent, there’s a whole lot of exploration still to do.

World Potato Congress tuber the biggest ever

Anyone going to the huge World Potato Congress in Beijing next week? Looks like the International Potato Centre is sending quite a delegation. As ever, we’d love to hear from you.