- Worldwide evidence of a unimodal relationship between productivity and plant species richness. Grassland richness maximal at intermediate productivity levels.

- Cytoplasmic genome types of European potatoes and their effects on complex agronomic traits. Interesting relationships between cytoplasmic type on one hand and tuber starch content and resistance to late blight on other.

- Enhancing the Conservation of Crop Wild Relatives in England. 148 priority species, half of them not in ex situ at all. But there’s no excuse for that now.

- Genetic rescue to the rescue. Meaning an increase in population fitness, especially of rare species, owing to new alleles. Genomics will help by choosing the new alleles better, and monitoring the results.

- Diversity and relationships of Crocus sativus and its relatives analysed by IRAPs. No variation in the allotriploid cultigen, lots in the closely related species. Let the resynthesis begin.

- Economic analysis of Kusmi lac production on Zizyphus mauritiana (Lamb.) under different fertilizer treatments. That would be the scarlet resin secreted by some insects. NPK needed. No word on genetic differences.

- Parallel Domestication of the Heading Date 1 Gene in Cereals. Same QTL in sorghum, foxtail millet and rice, but different alterations of it. Multiple domestication for sorghum, single for foxtail millet.

- DNA based iPBS-retrotransposon markers for investigating the population structure of pea (Pisum sativum) germplasm from Turkey. No geographic structure for the landraces.

- The two-speed genomes of filamentous pathogens: waltz with plants. Fungi and oomycetes quite different genetically, but both have regions of genome which change rapidly to make them good pathogens. Bastards.

- The flowering of a new scent pathway in rose. Can we have our nice-smelling roses back now, please?

- AFLP assessment of the genetic diversity of Calotropis procera (Apocynaceae) in the West Africa region (Benin). Not just a weed, used in cheese-making, of all things.

Digital filmmakers (and others) tackle African leafy greens

I came across this cool video about African indigenous vegetables via the Horticulture Innovation Lab newsletter. Made by a student at Rutgers University’s Center for Digital Filmmaking, it describes work led by Jim Simon of Rutgers and Steve Weller of Purdue University in Kenya and Zambia on growing and marketing plants like African nightshade (Solanum scabrum?), amaranth (Amaranthus spp), and spider plant (Cleome gynandra).

There’s another video on the website too. Well worth watching both, and indeed following the blog.

And if you want more video on African leafy greens, they feature in several episodes of Shamba Shapeup, Kenya’s version of Extreme Makeover: Farm Edition.

Oh, and BTW: vote for me!!! I’m only about a thousand or so “likes” behind the leader. Ok, it’s a mere photo rather than a video, but still…

Oh, and BTW: vote for me!!! I’m only about a thousand or so “likes” behind the leader. Ok, it’s a mere photo rather than a video, but still…

Searching for Rose Honey

We have on occasion blogged about “European” crops (and indeed livestock) being grown far from home, and how that sometimes serves to save varieties that have, for whatever reason, been lost back in the old country. Here’s another example, courtesy of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and its newsletter.

Ci Zhong, a Tibetan-Naxi village nestled in the Upper Mekong Valley, is renowned for its Catholic Church, which was built by French missionaries in 1914 AD. The French brought the first grape vine to the valley at about the same time. Ci Zhong locals inherited the techniques of vineyard cultivation and wine making from the French and do not use synthetic fertilizers or pesticides in their fields. Today, they are still growing the grape variety, Rose Honey, brought by the French a century ago. This grape variety has already died out in the rest of the world, due to a disease that wiped out almost all grape plantations in Europe at the time. About 160 kilometres north along the valley, the Naxi people of Bamei village have also starting cultivating a variety of grapes — Cabernet Sauvignon.

I can’t be sure about the statement that Rose Honey is extinct (except for its foothold in the Upper Mekong, that is) but that’s certainly what the internet seems to think. And I could’t find it in the European Vitis Database or the Vitis International Variety Catalogue or the US collection. But who knows, maybe it survives in some Baja mission oasis or Cape homegarden? In the meantime, I wonder if the French are going to ask for repatriation.

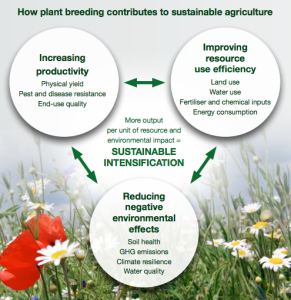

Plant breeding for sustainable agriculture

From a useful public awareness pamphlet on the importance of plant breeding, courtesy of the British Society of Plant Breeders.

From a useful public awareness pamphlet on the importance of plant breeding, courtesy of the British Society of Plant Breeders.

Featured: Diversity

Matthew parses “diversity,” as used by Secretary Vilsack:

I wasn’t there, but I have heard him speak about “diversity” several times before and he usually brings diversity up in the context of types (organic, conventional, biotech) and scales of farming systems. I’ve also heard him bring it up in terms of racial and gender diversity in farming.

So, probably NOT crop diversity? Seems a pity.