News that the Organic Research Centre has launched the ORC Wakelyns Population, an unusual new wheat “variety”, inspired Dr Salvatore Ceccarelli to write this blog post for us about his own efforts in a similar vein. He describes a different breeding paradigm, one based on providing farmers with lots of diversity, rather than with a single Next Big Thing.

One of the global issues most frequently debated today is the loss of biodiversity. What’s not often mentioned is that this can happen within agricultural as well as natural ecosystems, and that it can then have an effect on the ability of farmers to adapt to climate change, on food security and on human health.

In 2008, at ICARDA, we dusted off the old idea of evolutionary breeding to bring biodiversity back into farming systems. We made large, widely diverse populations of barley, bread wheat and durum wheat by mixing lots of F2 lines. And I mean lots: 1600 in the case of barley, 2000 in the case of bread wheat and 700 for durum wheat. The populations went to different countries, including Jordan, Algeria, Eritrea, Iran, and lately even Italy. In Ethiopia, a specific population was made based more specifically on Ethiopian germplasm.

The objective was to provide farmers with what could be defined as an evolving gene bank. Because of natural crossing, the seed which is harvested from these populations is never genetically the same as what was sown. In other words, the populations evolve continuously, becoming progressively better adapted to the conditions (soil, climate and agronomy) in which they are grown — and in the long term to climate change.

We thought that as the populations evolved, farmers would be able to use them as a source from which to select, possibly with the participation of scientists, ever better adapted varieties. However, it went further than that. Iranian farmers started reporting that the evolutionary populations could themselves be used as crops, as they were high yielding, stable and did not require chemical protection against pests. As a result, the evolutionary populations of barley and wheat spread through 17 provinces in Iran, and new evolutionary populations are being established in rice and corn.

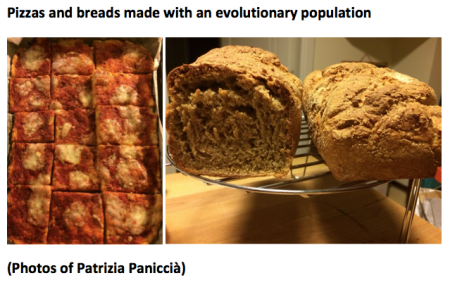

But perhaps the best finding was the one made by Iranian bakers: the bread made with the evolutionary population of bread wheat soon became a commercial success, not only because of its taste and flavour, but also because it was tolerated by people affected by allergies.

We are now having the same experience in Italy, where evolutionary populations of barley, durum wheat and bread wheat are grown in several regions: in Marche, bread made with the flour of the bread wheat population is now in great demand.

And an evolutionary population of zucchini, of all things, is currently grown by an organic farmer and new populations are being formed in beans and lettuce.

All these cases show that cultivating diverse populations can combine increasing biodiversity in farmers’ fields, adapting crops to climate change, and producing more, healthier, tastier food.