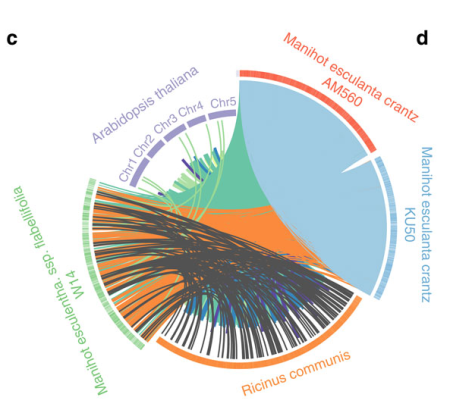

- Genetic diversity in shea tree (Vitellaria paradoxa subspecies nilotica) ethno-varieties in Uganda assessed with microsatellite markers. Three geographic populations revealed by SSRs, not much related to the folk classification.

- Malaysian weedy rice shows its true stripes: wild Oryza and elite rice cultivars shape agricultural weed evolution in Southeast Asia. The weed is caught in the middle and swings both ways.

- Farmers without borders—genetic structuring in century old barley (Hordeum vulgare). Nordic barley structured latitudinally, with lots more variation within landrace accessions than now, according to historical specimens.

- The Agrodiversity Experiment: three years of data from a multisite study in intensively managed grasslands. Does increasing plant diversity in intensively managed grassland communities increase their resource use efficiency? No idea, but here’s the data from a huge multi-site experiment. Go crazy.

- Genetic diversity in selected stud and commercial herds of the Afrikaner cattle breed. It’s doing just fine, genetically, despite recent declines in numbers.

- The African baobab (Adansonia digitata, Malvaceae): Genetic resources in neglected populations of the Nuba Mountains, Sudan. Maybe a little more variation in homesteads compared to the wild. Maybe.

- Seeing the trees as well as the forest: The importance of managing forest genetic resources. The first State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources and the first Global Plan of Action for the Conservation, Sustainable Use and Development of Forest Genetic Resources summarized: exchange, test in common gardens, and be clever with genetics, in breeding, management and restoration.

- Are small family farms a societal luxury good in wealthy countries? Rich countries don’t mind inefficient farms because they look nice.

- DIVECOSYS: Bringing together researchers to design ecologically-based pest management for small-scale farming systems in West Africa. Where do I sign up?

- Ecosystem governance in a highland village in Peru: Facing the challenges of globalization and climate change. Big Dairy doing for Andean crops.

- Intensive agriculture reduces soil biodiversity across Europe. What they said.

- The climate of the zone of origin of Mediterranean durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) landraces affects their agronomic performance. 4 main climatic zones, accounting for up to 30% of variation in important evaluation traits. FIGS, anyone?

- Indicators for the on-farm assessment of crop cultivar and livestock breed diversity: a survey-based participatory approach. And only 5 of them too!

Speaking about Speaking of Food

This special issue, “Speaking of Food: Connecting basic and applied plant science,” aims to provide concrete examples of how a wide range of basic plant science, the types of scientific studies commonly published in AJB, are relevant for the future of food. This Special Issue was inspired by Elizabeth A. Kellogg’s 2012 Presidential Address to the Botanical Society of America, and resulted in part from a symposium and colloquium by the same name that took place at the 2013 Botany meetings in New Orleans, LA. The issue editors are grateful to the Botanical Society of America, the American Society of Plant Taxonomists, and the Torrey Botanical Society for support of this work.

Special issue of the American Journal of Botany, that is. Alas, only one of the papers, the one on strawberries, is open access, though.

Comparing the niches of wild, feral and cultivated tetraploid cottons, Part 2

We’re trying something new for us this week. Dr Geo Coppens co-authored an interesting paper 1 recently which brings together a number of our concerns: domestication, diversity, crop wild relatives, spatial analysis… He’s written quite a long piece about his research, which we’ll publish here in three instalments. This is the second instalment. Here’s the first, in case you missed it.

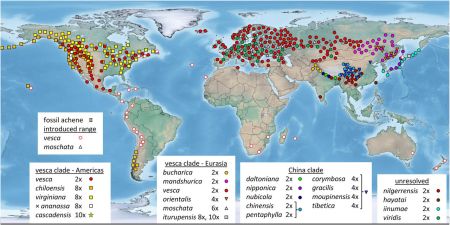

To investigate the origin of cultivated cotton in the New World, we also had to define the distribution of the wild precursors, which meant distinguishing True Wild Cotton (TWC) populations from feral (secondarily wild) populations. We first defined five categories: (1) TWC populations, which were described as such by cotton experts with consistent ecological and/or morphological criteria; (2) wild/feral cottons, reported to grow in protected areas and/or forming relatively dense populations in secondary vegetation; (3) feral plants living in anthropogenic habitats (field and road margins); (4) cultivated perennial cottons; and (5) plants of indeterminate status. We then organized our extensive dataset of locality information from herbaria and genebanks in the same way as Russian nesting dolls.

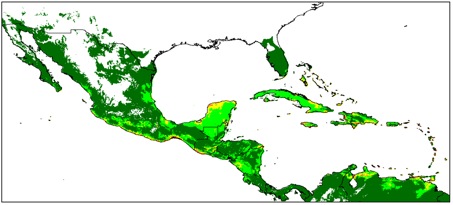

Avoiding the problematic comparisons between consecutive categories, we first modelled G. hirsutum distribution based on the whole sample, then reducing the sample to ‘feral’+‘wild/feral’ + TWC , then to ‘wild/feral’+TWC, and finally to TWC alone. Thus, we could see that the distribution model (we used the Maxent software for niche modelling) was not significantly affected by the successive removals of specimens classified as indeterminate, cultivated, or feral. Only the model based on TWC populations diverged very clearly, their distribution being severely restricted to a few coastal habitats, in northern Yucatán and in the Caribbean, from Venezuela to Florida (Figures 1 and 2).

A principal component analysis on climatic parameters confirmed the absence of clear differences among the climatic niches of cultivated, feral, and ‘wild/feral’ populations, contrasting strikingly with that of TWC populations, restricted to the most arid coastal environments. The TWC habitat’s harsh conditions are quite certainly related to the fact that “Gossypium is xerophytic and that even its most mesophytic members are intolerant of competition, particularly in the seedling stage” (Hutchinson, 1954). The proximity to the sea plays a role itself, for these “extreme outpost plants” (Sauer, 1967). Indeed, as Fryxell (1979) puts it, wild tetraploid cottons are strand plants adapted to mobile shorelines, with impermeable seeds adapted to salt water diffusion. The instability of their habitat “is in itself highly stable” and very ancient, so “that the pioneers are simultaneously old residents”.

Extrapolating this TWC climatic model to South America and Polynesia points towards places where other wild representatives of tetraploid Gossypium species have been reported, which gives a strong example of niche conservatism. Thus, the distribution model has perfectly captured those conditions that are related to both biotic and abiotic constraints for the development of TWC populations.

To be continued…

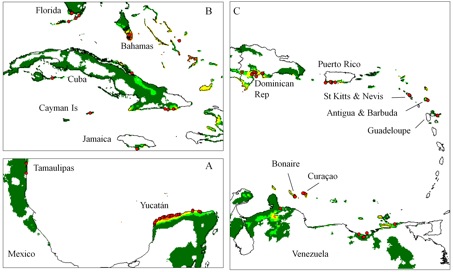

Rocking the cassava genome

One is of course over the moon about the publication of the cassava genome, with its now de rigueur amusing representation of the relationship between it and the genomes of other species, in this case in the shape of a cluster of tubers. But could not the Nature Communications editor have been a little more careful about those species names in one of the other figures?

Nagoya and the Plant Treaty

As we celebrate (or whatever) the coming into force of the Nagoya Protocol, I think it’s worth reminding ourselves that in the agricultural sector there has been an Access & Benefit Sharing system in place for a while, under the “Plant Treaty,” for that subset of biodiversity which is plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Now what we need is, in the jargon, “mutually supportive implementation at the national level.” But there’s been a meeting on that, and

Participants agreed that joint implementation (of both Nagoya Protocol and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture) should be kept in mind by all actors and that collaboration by relevant authorities should be intensified on the basis of mutual trust.

So that’s allright then.