- Progress and prospects for interspecific hybridization in buckwheat and the genus Fagopyrum. Not easy.

- Mechanisms for the successful biological restoration of the threatened African pencilcedar (Juniperus procera Hochst. ex. Endl., Cupressaceae) in a degraded landscape. Needs help from local Acacia. Isn’t diversity wonderful?

- Tapping latex and alleles? The impacts of latex and bark harvesting on the genetic diversity of Himatanthus drasticus (Apocynaceae). Tapping latex leads to loss of genetic diversity, but they have a plan for sustainable harvesting.

- Analysis of genetic diversity in berari goat population of Maharashtra state. “Berari is not a recognized breed but a well established local population of goat which is yet to be fully explored for its phenotypic and genetic aspects.” So what would it take to recognize it? This paper?

- Molecular phylogeny of Indian horse breeds with special reference to Manipuri pony based on mitochondrial D-loop. It’s the most different of the 5 breeds of the sub-continent (yes, apparently only 5), and the most similar to the Thoroughbred.

- Estimation of genetic diversity of the Kenyan yam (Dioscorea spp.) using microsatellite markers. Most variation within provinces. And?

- Morphological and genetic diversity of European cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos L., Ericaceae) clones in Lithuanian reserves. Enough morphological variation to think about domestication; enough molecular marker variation to think about writing another paper.

- Down deep in the holler: chasing seeds and stories in southern Appalachia. It’s all about the friendships.

- Pepper (Capsicum spp.) Germplasm Dissemination by AVRDC – The World Vegetable Center: an Overview and Introspection. Here come the numbers: 8,165 accessions of Capsicum conserved, 11% of global total; 6,008 genebank accessions (20%) and 23,972 improved advanced lines (80%) distributed in 25 years; 51 open pollinated and hybrid cultivars of hot and sweet peppers commercialized by public and private sectors in South Asia, West Africa, Central Asia and the Caucasus since 2005.

- Genetic characterization of local Italian breeds of chickens undergoing in situ conservation. Breeds are breeds.

Agrobiodiversity meta-calendar needed!

Yesterday’s Nibble scared me, I don’t mind admitting. So many meetings and other events going on, all over the world, all the time. What is a poor boy interested in agrobiodiversity to do to keep track?

Here’s what, since you ask. What we need is an app — or a real live human being, I don’t care — to regularly go through the following online calendars, extract the events of most obvious relevance to agricultural biodiversity, and plonk them on another, bespoke online calendar:

- CGIAR

- Young Professionals for Young Professionals in Agricultural Research for Development

- Global Donor Platform for Rural Development

- Agrifeeds

- Convention on Biological Diversity

Now, you tell me, is that too much to ask for?

LATER: Cédric makes some additional suggestions in a comment, but I only really like these two:

How to save seed potatoes

You may have formed the impression that saving your own seed potatoes (as opposed to true potato seed) is fraught with danger and liable to lay waste to the local economy. Fear not, it can be done, and while it is a bit late in the year for Northern gardeners to undertake, those in the South might welcome the news, and northerners can start to plan for next year.

It is true that simply saving the smaller tubers from your normal harvest is not best practice, because they may well be carrying diseases. Instead, plant a row of potatoes specifically to produce seed tubers. Keep a close eye on them, and remove any that do seem less vigorous or diseased in any way. Quite early in the season, perhaps late July or early August (in the UK) cut the tops off completely. Exact times will vary, so have a gentle root around beneath the bush and confirm that there are some small tubers there, and then maybe leave the plants another week. Removing the tops prevents aphids from delivering the pathogens they transmit to potatoes, and doing so early is a good idea because the aphids accumulate more pathogens as the season progresses. Dig up the tubers, gently again, because the skins might not have set fully yet, and don’t bother trying to get them too clean at this stage. Set them under cover but in good sunlight for 3–4 days, making sure there is good air circulation around them. They skins may well turn green. This is a good thing, as it helps to make the tubers go dormant so that they don’t sprout prematurely. Gently brush any loose soil away, label the potatoes and store them in a cool, dark, frost-free place.

Rebsie had a lovely post about saving her potato diversity some years ago.

A slightly more advanced technique, especially if you didn’t manage to set aside some plants specifically, is to plant saved tubers into a large pot, using a sterile soil mix, as early in the season as you can. When the shoots are about 20 cm tall cut off the top 5 cm. Plant these cuttings into more sterile soil mix and grow them on. They will have rooted within about two weeks and can then be hardened off and planted out into the garden. You can even over-winter potatoes as cuttings if you can give them a frost-free environment.

You can go one step further yet, and produce your own micro-tubers, but that takes a well-equipped kitchen and a modicum of know-how about tissue culture. Or a small laboratory. It isn’t difficult, but nor is it for the faint-hearted. My own feeling, having explored this once before, is that people with an interest in edible biodiversity would beat a path to your door for clean, healthy stock, if only you were permitted to supply it.

Brainfood: Wild maize diversity, Bacterial test, Rice diversity, Marginal biofuels, Rice roots, Farm diversification and returns, Sorghum shattering, Thinking conservation, Ethiopian peas

- Complex Patterns of Local Adaptation in Teosinte. It’s down to the inversions and the intergenic polymorphisms.

- A Stringent and Broad Screen of Solanum spp. tolerance Against Erwinia Bacteria Using a Petiole Test. The best genotypes are all in one, easily-crossed series.

- Genetic diversity, population structure and differentiation of rice species from Niger and their potential for rice genetic resources conservation and enhancement. Both cultivated species, plus hybrids. More diversity within ecogeographic areas than among them.

- Use of DArT markers as a means of better management of the diversity of olive cultivars. Some potential duplicates found. But will anything be done about it?

- “Marginal land” for energy crops: Exploring definitions and embedded assumptions. Whether it’s a good idea to relegate biofuels to marginal land to protect food crops depends on what you mean by marginal.

- Coconuts in the Americas. They came from the Philippines. Well, the ones on the Pacific coast did anyway.

- Control of root system architecture by DEEPER ROOTING 1 increases rice yield under drought conditions. And it came from a genebank accession, no less.

- Landscape diversity and the resilience of agricultural returns: a portfolio analysis of land-use patterns and economic returns from lowland agriculture. You want resilient returns? You need large(ish), diversified farms.

- Seed shattering in a wild sorghum is conferred by a locus unrelated to domestication. But close to it.

- When the future of biodiversity depends on researchers’ and stakeholders’ thought-styles. You have to agree on more than just how you do it when you’re collaborating on a multidisciplinary conservation project. You also have to agree on why you’re doing it.

- Characterization of dekoko (Pisum sativum var. abyssinicum) accessions by qualitative traits in the highlands of Southern Tigray, Ethiopia. Endemic pea diversity arranged by altitude.

Trouble in Lima?

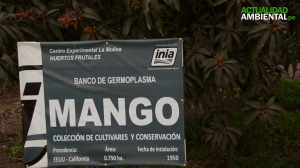

Is there a Pavlovsk situation brewing in Lima? 1 The Sindicato Único de Trabajadores del Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria, which is the labour union representing workers at the national agricultural research institute (INIA), which has its headquarters at La Molina, a suburb of Lima, certainly think so. In an article entitled “Ministry of Agriculture wants to convert 30 thousand square metres of orchards into offices” featuring copies of allegedly relevant documents and even a video, the union suggests that the orchards in question are in fact genebanks, collections of mango, avocado and chirimoya.

That would certainly be bad. But is it true? It does seem to be true that the ministry wants to build additional offices on its land in La Molina, and that the land in question holds fruit trees. But are the trees part of a genetic resources collection? That is not so clear. WIEWS confirms that Peru does indeed have multiple collections of mango, avocado and chirimoya, but none of them seems to be on INIA land in La Molina. Admittedly, collections are recorded from La Molina for two of those fruits, but they appear to be on the property of the nearby agricultural university, not INIA. The other collections are in other research stations in different parts of the country.

That would certainly be bad. But is it true? It does seem to be true that the ministry wants to build additional offices on its land in La Molina, and that the land in question holds fruit trees. But are the trees part of a genetic resources collection? That is not so clear. WIEWS confirms that Peru does indeed have multiple collections of mango, avocado and chirimoya, but none of them seems to be on INIA land in La Molina. Admittedly, collections are recorded from La Molina for two of those fruits, but they appear to be on the property of the nearby agricultural university, not INIA. The other collections are in other research stations in different parts of the country.

Of course, the information in WIEWS may be out of date. Discreet enquiries with sources in a position to know suggest that the unions may well be overstating their case, but I have been unable to find an official response from INIA. Meanwhile, the institute is busy setting up more genebanks. No, not in La Molina.

If anyone out there can help us get to the bottom of this, let us know. But while we’re on the subject of fruit tree collections, let me link to what I believe is a new(ish) version of the website of the National Fruit Collection of the U.K., which includes a handy database. You may remember that this collection, at Brogdale, also went through a period of uncertainty. Let us hope that the INIA collection, if indeed it is a collection, emerges from its vicissitudes as strongly as Brogdale has.