Matt Bennett of the Wellesbourne Seedbank at the University of Warwick is working on a dissertation on the impact of advances in DNA sequencing on the management of plant genetic resources. He is investigating how next generation sequencing technology can be used to improve the use of genetic diversity and the cost efficiency of seed management. If you know about this stuff, you can help him by doing a quick survey.

Do your efforts engage and impact local custodians of agrobiodiversity?

We are happy to pass on this request from Simran Sethi. Do get in touch with her, you wont regret it.

I am an environmental journalist focusing on the loss of biodiversity in our food system. This erosion of agrobiodiversity echoes through every part of our food system. It strips soil, seed, pollinators, crops, livestock and aquatic life of their ability to adapt to changes in the environment—and puts our entire food supply at risk.

This extinction of food is a process, not a singular event. It is buried in the soil, hidden within feedlots and immersed in the ocean. I addressed some of this in my recent TEDx talk on seeds as the buried foundations of food, but seek to highlight this issue more broadly in my upcoming book “Endangered Food: The Erosion of What and How We Eat.” Because eating is both an agricultural and cultural act, my narrative is focused on conservation through consumption; specifically, on efforts to save foods by eating them.

And this is where I seek your assistance. I recognize this issue is complex and that consumption presents its own set of challenges. As those intimately involved in biodiversity preservation, you have firsthand knowledge of the ways in which your efforts engage and impact custodian farmers and local communities. Food is the embodied history and cultural identity through which the public can understand and address the global challenge of genetic erosion. To that end, I welcome any case studies on the expansion of underutilized species (both on farms and in markets) and/or examples of eating as a compelling and delicious way to support biodiversity and reshape the future of food through lived experience.

I can be reached for any questions or comments on simran “at” simransethi.com. Thank you for your consideration.

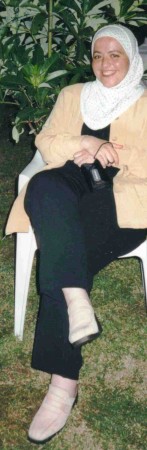

Suha Ashtar RIP

Dr Devra Jarvis of Bioversity International, formerly the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, reminisces about her late friend and colleague, Dr Suha Ashtar, on behalf of the global on-farm team.

It is with great sadness that we heard of the passing of Suha Ashtar on 17 April 2013 in Aleppo. Suha was one of the first members of the “in situ family” that over the years worked at Bioversity International to establish a scientific basis for on farm conservation of crop biodiversity, together with colleagues from Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Hungary, Mexico, Morocco, Peru and Vietnam. I remember my first meeting with Suha, when we were interviewing for the various regional staff to help me coordinate the global in situ programme, and being impressed by her lively and bright manner and her ability to forcefully express her own ideas and opinions. I still remember a short trip into the Italian countryside the core in situ project group took in a mini-bus, together with our donor, and the heated discussions about how the project should go, not to mention the calls for me to drive more slowly, as the back of the bus was shaking back and forth! Going through some old photos, I found a lovely one of Suha at the group dinner of a global meeting we had in Pokhara, Nepal in 1999 with colleagues from over 20 countries about working to support farmers in the assessment, management and gaining benefits from the conservation and use of traditional crop varieties. The dinner had followed long discussions and a hike up the hills nearby to meet with some local women and men farmers’ groups. Suha will be sorely missed by her colleagues and friends, and by myself especially as one of her first supervisors, when she was just setting out, young, intelligent and full of energy to start her career.

It is with great sadness that we heard of the passing of Suha Ashtar on 17 April 2013 in Aleppo. Suha was one of the first members of the “in situ family” that over the years worked at Bioversity International to establish a scientific basis for on farm conservation of crop biodiversity, together with colleagues from Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Hungary, Mexico, Morocco, Peru and Vietnam. I remember my first meeting with Suha, when we were interviewing for the various regional staff to help me coordinate the global in situ programme, and being impressed by her lively and bright manner and her ability to forcefully express her own ideas and opinions. I still remember a short trip into the Italian countryside the core in situ project group took in a mini-bus, together with our donor, and the heated discussions about how the project should go, not to mention the calls for me to drive more slowly, as the back of the bus was shaking back and forth! Going through some old photos, I found a lovely one of Suha at the group dinner of a global meeting we had in Pokhara, Nepal in 1999 with colleagues from over 20 countries about working to support farmers in the assessment, management and gaining benefits from the conservation and use of traditional crop varieties. The dinner had followed long discussions and a hike up the hills nearby to meet with some local women and men farmers’ groups. Suha will be sorely missed by her colleagues and friends, and by myself especially as one of her first supervisors, when she was just setting out, young, intelligent and full of energy to start her career.

Apologies for the absence of email updates

Many thanks to an attentive subscriber who told us that updates were no longer arriving by email. Apparently they stopped around 20 April; I have no idea why. This has not affected those who subscribe directly in a feed reader (which is why I did not myself notice). I’m trying to sort this out as quickly as possible, and I hope normal service will be restored soon.

(Of course, if you only subscribe by email, you may not see this …)

Apple diversity trends: they are what they are

One of the nice things about being slow off the mark is that sometimes someone else will do the job for you. So it was with the splashy story in Mother Jones about the decline in apple diversity in supermarkets. Instead of having to point out some of the misleading hyperbole in that story, I can just point you to Alex Tabarrok, an economist with an interest in agriculture and diversity. Better yet, it offers me an opportunity to set Tabarrok himself straight. The view of diversity espoused by “the innovative Paul Heald and co-author Sussanah (sic) Chapman” that Tabarrok lauds is not one shared by many actual plant geneticists. You can talk about variety names, or allele combinations, or genetic distances, and get whatever answer you’re looking for; diversity is higher, lower or unchanged.

The geographical scale over which you measure diversity matters too, and Tabarrok explains that well:

Consider the simplest model (based on Krugman 1979). In this model there are two countries. In each country (or region), consumers have a preference for variety but there is a tradeoff between variety and cost, consumers want variety but since there are economies of scale – a firm’s unit costs fall as it produces more – more variety means higher prices. Preferences for variety push in the direction of more variety, economies of scale push in the direction of less. So suppose that without trade country 1 produces varieties A,B,C and country two produces varieties X,Y,Z. In every other respect the countries are identical so there are no traditional comparative advantage reasons for trade.

Nevertheless, if trade is possible it is welfare enhancing. With trade the scale of production can increase which reduces costs and prices. Notice, however, that something interesting happens. The number of world varieties will decrease even as the number of varieties available to each consumer increases. That is, with trade production will concentrate in say A,B,X,Y so each consumer has increased choice even as world variety declines.

I think something similar can be said of plant breeding. The number of parents in a popular variety’s pedigree may be higher today than it used to be, but the number of parents contributing to today’s popular varieties would, I reckon, be lower than it was, say, 50 years ago.

Looking at Krugman’s model of apple globalization from the Himalayas, an article in the Christian Science Monitor informs us that the first Red Delicious apples arrived their in 1916 in the care of Samuel Evans Stokes, a Quaker Missionary from Philadelphia. Stokes thought apples would flourish in the Shimla hills, and they did. But the climate that attracted Stokes and his apples has changed, and Indian orchardists are finding it hard to respond. Some are apparently giving up on Red Delicious and trying Fuji, Gala and other, newer varieties that may prove better (and happen to be favoured by global apple markets). Some are even switching away from apples.

So, is diversity increasing or decreasing? I’m not getting into that.