ACIAR has just published a huge study of the impact of IRRI’s rice breeding work in SE Asia. The press release has the key numbers:

- “Southeast Asian rice farmers are harvesting an extra US$1.46 billion worth of rice a year as a result of rice breeding.”

- “…IRRI’s research on improving rice varietal yield between 1985 and 2009 … [boosted] … rice yield by up to 13%.”

- “…IRRI’s improved rice varieties increased farmers’ returns by US$127 a hectare in southern Vietnam, $76 a hectare in Indonesia, and $52 a hectare in the Philippines.”

- “The annual impact of IRRI’s research in these three countries alone exceeded IRRI’s total budget since it was founded in 1960.”

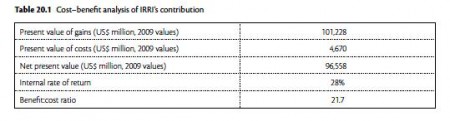

But I guess the figure the Australians were really after is that in the final table:

A pretty decent return.

Good to see the pioneering work of IRRI (and others) in documenting pedigree information in a usable way recognized — and indeed made use of. And good to see the International Network for Genetic Evaluation of Rice (INGER) and its use of the International Treaty’s multilateral access and benefit sharing system highlighted in the study as a model for germplasm exchange and use. Of course one would have loved to see the genebank’s role in producing the impact also recognized, rather than sort of tacitly taken for granted as usual, but maybe the data can be used to bring that out more in a follow-up.

I see another couple of opportunities for further research, actually. There is little in the study about the genetic nature of the improved varieties that are having all this impact. To what extent can their pedigrees be traced back to crop wild relatives, say? And, indeed, how many different parent lines have been involved in their development, and how genetically different were they? That will surely to some extent determine how sustainable these impressive impacts are likely to be.