As everyone and her dog ventures an opinion of how much more food will be needed to properly feed how many more mouths by when, it is worth bearing in mind an idea that was a little bit hidden in Oliver Morton’s wonderful introduction to The Anthropocene, in The Economist a couple of weeks ago.

Although nitrogen fixation is not just a gift of life — it has been estimated that 100m people were killed by explosives made with industrially fixed nitrogen in the 20th century’s wars — its net effect has been to allow a huge growth in population. About 40% of the nitrogen in the protein that humans eat today got into that food by way of artificial fertiliser. There would be nowhere near as many people doing all sorts of other things to the planet if humans had not sped the nitrogen cycle up.

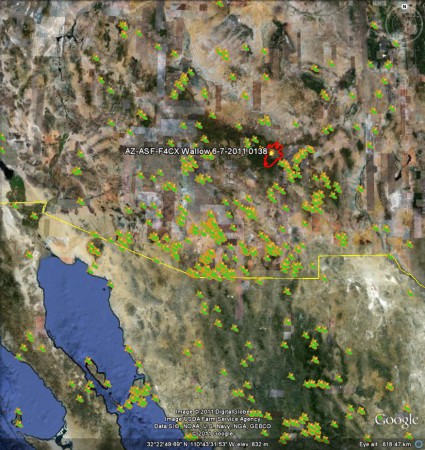

There’s a chart, too.

Industrial nitrogen fixation does not, of course, require oil, but it does require lots of cleaner, cheaper energy, and there’s still no sign of that just around the corner.