There’s a really bad fire spreading in Arizona. 1

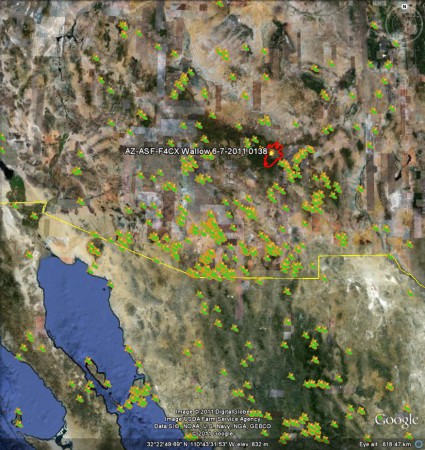

You can donwload all kinds of stuff about it, and even post your experiences of it on Facebook. But can you find out whether any crop wild relatives are threatened by it? Well, sure: all you have to do is go off to GBIF, and choose a likely genus (Phaseolus, say), and download the records, and mash them up in Google Earth with the latest fire perimeter data or whatever. 2 Like I’ve done here:

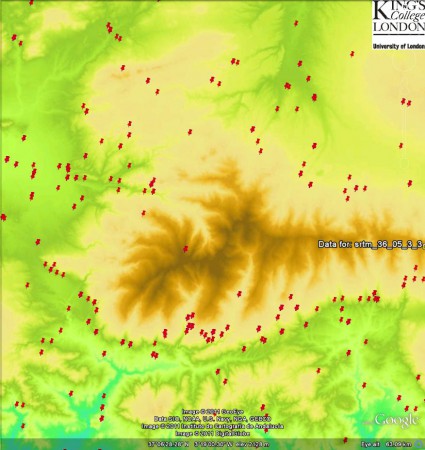

Coming in closer, and using the NASA GeoTIFF instead of the normal Google Earth imagery, you can put yourself in the position of being able to make some reasonably intelligent guesses about what might be happening to some of these populations, and the genepool as a whole in the area:

But what I really meant is that there ought to be a way to do this automagically, or something. Anyway, it is sobering to reflect that while all hell is breaking loose in Arizona, not that far away to the northeast, in the peaceful surroundings of the Denver Botanical Garden, Anasazi beans are enjoying their day in the sun, utterly oblivious of the mortal threat faced by some of their wild cousins. It’s a cruel world. And there’s a point in all this about the need for complementary conservation strategies that’s just waiting to be made. Isn’t there?