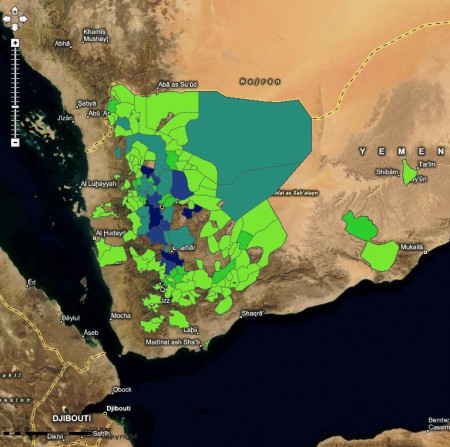

For what it’s worth, I have enormous admiration for IFPRI and its products. Not that they give a damn about that, but I just want to get it out of the way before slamming them. First, the news item on a new interactive atlas of food security in Yemen doesn’t have a link to the new interactive atlas of food security in Yemen. Not to worry, though, Google is your friend, 1 and it’s not all that difficult to find the relevant page on the IFPRI website. But then the new interactive atlas of food security in Yemen turns out to be nice enough as to content, but highly frustrating to use. No way to download or export maps. I had to get the thing below (showing barley cultivation, for the record) through a screen grab. Yuch.

And no way to mash up the results with other stuff. Like, for example, barley accessions in Genesys. Which in contrast you can export in a number of ways.

Oh, sure, there are some words of explanation, if not excuse:

The online version does not require installing software but it is more limited in the sense that the underlying data cannot be accessed by the user (unlike in the case of the download of the data package).

But I don’t believe it would be that difficult to allow some sort of exporting online. Maybe I’m wrong. Someone tell me, please.

So, anyway, two maps which cry out to be looked at together, for example in Google Earth, and no way of doing so, at least that I can see. As I say, very frustrating. Who do I complain to? There someone in the CGIAR to whom I can go with a query about spatial data, right? Isn’t there?