Reading The great Vitamin A fiasco, by Professor Michael Latham of Cornell University, I had to force myself not to punch the air and shout “Yes!”. More than once. Mainly because he provides the backstory and the supporting evidence that makes sense of a deep-seated feeling I’ve long had, that food has been sidelined as a response to malnutrition.

Reading The great Vitamin A fiasco, by Professor Michael Latham of Cornell University, I had to force myself not to punch the air and shout “Yes!”. More than once. Mainly because he provides the backstory and the supporting evidence that makes sense of a deep-seated feeling I’ve long had, that food has been sidelined as a response to malnutrition.

No, I’m not exaggerating. Richer countries emphasize eating more and more diverse fruit and vegetables for better health. No matter that few people pay any attention. The advice is sound. Developing countries? Fuggedabout it. High-tech, simplistic solutions are the order of the day, often purveyed as medical cures for specific diseases. Latham’s critique is pretty devastating. He shows, first off, that massive doses of vitamin A — the overwhelmingly dominant solution to vitamin A deficiency — have had little impact on child mortality. Where deaths are falling, and they are, there is no evidence that this is caused by vitamin A supplements. Indeed, in some well-conducted studies vitamin A is associated with more deaths.

Latham points out the many ways in which the medical establishment has captured micronutrient malnutrition and how to deal with it, in the process blocking other approaches that often have multiple benefits. Not only are vitamin A interventions ineffective, he says:

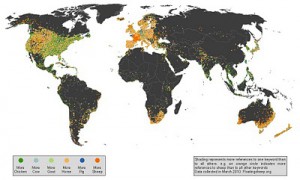

They use up precious human and material resources. Most of all, they impede other approaches to the prevention of vitamin A deficiency, best initiated at national and local level, which need much more support. These include breastfeeding, and the protection and development of healthy, affordable and appropriate food systems and supplies. Such approaches also protect against other diseases, are sustainable, enhance well-being, and have social, cultural, economic and environmental benefits.

Food-based approaches were the primary recommendations adopted when micronutrient deficiencies began to be recognized and tackled in the early 1990s, but they were comprehensively eclipsed by the merchants of silver-bullets, who offered simplicity and, say it softly, profits and power. Latham carefully documents the shift from food to pharmaceuticals and shows how it was not sustainable, ignored and suppressed evidence, blocked other approaches, thus denying developing countries their multiple benefits, and might actually have done more harm than good, especially where megadoses of vitamin A were given to children regardless of need. But he is also hopeful, warning that, in the absence of evidence, donor fatigue may at last be setting in. Will developing countries continue these efforts when they have to pay for them themselves?

When explicitly asked if China would take over funding for this if the donor ended its support, officials in the Chinese ministry of health consulted among themselves and replied: ‘Anyone who wants to come to China to do something beneficial for our children is welcome’. (Greiner T, personal communication). Asian elegance in delivering difficult messages is always impressive.

Maybe countries will then be willing to adopt food-based approaches, and we won’t have to keep bleating about agricultural biodiversity’s potential contributions being ignored. Now that really would be something to punch the air for.