You know how the internet is. Endless rabbit holes down which to lose oneself. Some questions answered. Others, not so much. New ones arise. Here’s an example. It all started with the Mosaic of the Seasons in the 5th century Byzantine church at Petra in Jordan. I visited the site last week and thought the agrobiodiversity-themed mosaics wonderful.

That got me thinking about Nabatean crops more generally. What did these people grow in the middle of the desert? Did it include the plants depicted in these mosaics? The Nabateans were known as spice (and incense) traders, but more as middlemen rather than actual producers. Why, indeed, did they find it necessary to grow anything at all in such a harsh environment? Couldn’t they have traded for everything they needed, sitting astride a major trade route from the East to Rome?

So I googled a bit, and it turns out there’s a book called Nabatean Agriculture. Or Al-Filahah al-Nabatiyah in fact, written by a 9th century Mesopotamian scholar called Ibn Wahshiyah. Unfortunately, though the Arabic text is online, I could not find anything that I could actually read on the contents of the book beyond that it includes “a wealth of knowledge on the preparation of basic foods from the agricultural products mentioned throughout the book.” Frustrating.

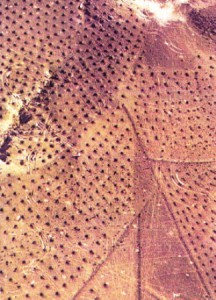

However, I did find an enormous amount on the sophisticated water management practices of the Nabateans, for example in the supporting document to Israel’s proposal for inscription of the “Desert Cities of the Negev” as a World Heritage Site. It’s a huge pdf, so watch out, but it does have great descriptions, starting on page 108, of the channels, damns and cisterns these communities built to save and manage water in a region with less that 100mm of annual rainfall. Some of these practices are in fact being revived. One consists of enigmatic piles of rocks called tuleilat el anab in Arabic, which means “grape mounds.” 1

They measure 1 m in diameter by 30 cm in height and in some places extend for several square kilometers. So it’s not just pleasure gardens we’re talking about. The prevailing view seems to be that the grape mounds were intended to enhance the flow of run-off water into agricultural terraces. Their name is the only clue to the crops grown by the Nabateans that I’ve been able to find 2, apart maybe for those mosaics. There must surely be some archaeobotanical evidence somewhere? More rabbit holes beckon.