The philosophy behind the One Acre Fund is clearly of a piece with that of the Millennium Villages and the Malawi fertilizer subsidy programme: giving farmers seeds, fertilizers, some advice and a market outlet will do wonders for livelihoods. In a way, it’s a no-brainer: of course it will! And it seems churlish and petty and ungenerous to add the canonical “at least for a while” qualifier, and bring up sustainability and resilience and suchlike when lives are at stake, the need urgent, and the amounts of money involved relatively small. So I won’t go down that route. But I will point out, and not for the first time, that if you are going to do something like this, or this, please first have a look at the amount and uniqueness of the agrobiodiversity you may end up displacing. And I’ll also repeat, again not for the first time, that such initiatives are why we need a global early warning system for genetic erosion. It’s easy to start. All we need is a participatory online mapping platform. You can even submit data via SMS these days!

Bee story with a sting in its tail

We’ve been a bit forgetful lately, not submitting items to Scientia Pro Publica, one of the most popular science blog carnivals around. But that doesn’t mean we’ve ignored the latest edition, at Genetic Inference. There’s a bunch of stuff there on climate change, and a link to a long post on David Roubik’s 17-year quest to understand the impact of African Killer Bees.

We nibbled Science Daily’s take on the original scientific paper, but on an amazingly busy day. So it is good to see Greg Laden take a somewhat longer view. To the press release, which he thoughtfully copies, Laden adds the observation that “the so called “African Killer Bees” are nothing other than the wild version of the honey bee,” and points out that people have a hard time relating loving, gentle European honey bees to these killers out of Africa’s dark heart. The interbreeding of wild and domesticated honeybees restored some aggression to domestic stocks and in the process of “Africanizing” them also boosted their honey-gathering abilities.

Roubik’s study concluded that although there have been swings in populations of various bee species, pollination has not suffered. Local bees, sometimes outcompeted by Africanized honeybees, are finding other flowers to sustain them. Most of the local plants are still doing fine, and some that are favoured by local bee species have even spread. But Roubik also sounded a cautionary note that hinges on the insurance value of plant biodiversity.

Basically we’re seeing ‘scramble competition’ as bees replace a lost source of pollen with pollen from a related plant species that has a similar flowering peak–in less-biodiverse, unprotected areas, bees would not have the same range of options to turn to.

That’s crucial. Roubik studied bees in “Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve — a vast area of mature tropical rainforest in Quintana Roo state on the Mexican Yucatan”. With fewer flower species among which to choose, local bees might not do so well. On the other hand, if the flower species aren’t there, they won’t suffer from the loss of local bees.

Helping the guarango

And here’s another nice agrobiodiversity video, though not part of the contest Jeremy refers to in the previous post. It’s about the guarango (Prosopis pallida) tree of the Peruvian coast. Once central to pre-Columbian culture for its pods, wood and ecosystem services, it is now “near extinction in the Ica-Nasca region.” But it’s not going down without a fight, and it is getting some help, for example from a Kew reforestation project. Thanks, Charlotte.

A Commission meets

All go at FAO again with the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture holding its 12th meeting. One of the things on the agenda is consideration of the 2nd report on the State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (the final version is available online as a large pdf). There’s also a side event on crop wild relatives, among others. IISD has the low-down every day.

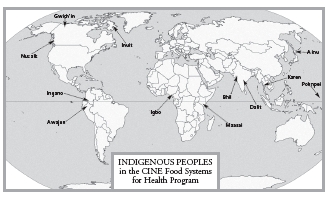

Indigenous food book online

I don’t think I made it sufficiently clear when I last blogged about the FAO publication Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems, published with the Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment (CINE) that it is available in its entirety online as a pdf (9MB). Thank you, FAO!