![]() Good news for sun-loving Germans. By 2071-2080 parts of their country are going to have the climate that parts of Greece have now. That’s according to a paper in Plant Ecology which ran a bunch of climate change models for Europe. 1 Have a look at the money map.

Good news for sun-loving Germans. By 2071-2080 parts of their country are going to have the climate that parts of Greece have now. That’s according to a paper in Plant Ecology which ran a bunch of climate change models for Europe. 1 Have a look at the money map.

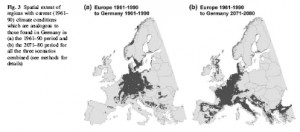

On the left are today’s Germany-like climates in Europe. On the right is where Germany’s future climates can be found right now. Germany will basically have the climate that France has now, but with significant bits of Spain, Italy, Greece and even Turkey thrown in.

Not surprisingly, the authors go on to suggest that this will have consequences for the country’s flora. They calculate that up to 1300 Spanish and Portuguese plant species not currently growing in Germany could find climatic conditions there to their liking by 2071 (edaphic conditions and the biotic environment are another thing, of course). That would be quite a significant northeasterly migration. It would be interesting to know how many crop wild relatives that might include. It would be even more interesting to know what will happen to individual crops, the olive and grape, for instance.

Today’s young Germans might be able to enjoy Mediterranean holidays at home by the time they retire, with the diet to match, zero-food-miles olive oil included. Who said climate change was going to be all bad?