Not for birds in Africa, apparently — and surprisingly, at least to me. 1 A recent paper looked at likely turnover of species in Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in Africa under a range of climate change scenarios. The results showed that although there would be significant shifts in the species composition of individual IBAs, overall about 90% of 815 endangered species “are projected to retain suitable habitat by 2085 in at least one IBA where they occur currently.” And some IBAs will become newly suitable for some species. Only a few endangered species will lose all suitable habitat from the IBA network.

Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge the importance of the shifts in species distribution and suggest a number of recommendations. In particular, the results highlight the need for regionally focused management approaches. For example, increasing the number and size of protected areas, providing ‘stepping stones’ between habitats and protected areas and restoring critical types of habitat, as well as ensuring that the current IBA network is adequately protected into the future.

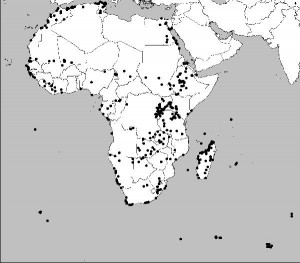

Sensible recommendations, which would apply all the more strongly to any similar network for crops wild relatives, say, which don’t by and large have the mobility of birds. 2 We need to carry out a similar resilience study for CWRs in protected areas, I would suggest. But also, do we know how good the IBAs are at capturing CWR diversity? I suspect when people look at CWR distributions in protected areas, it is mainly national parks and the like that they consider, rather than such specialized things as IBAs, but I could be wrong. 3 Here’s the distribution of IBAs in Africa. I seem to be having a thing about maps of Africa lately.

The Kenya Forest Service is one of the forces behind butterfly farming projects around the country. According to the latest KFS annual report (which I found out about from

The Kenya Forest Service is one of the forces behind butterfly farming projects around the country. According to the latest KFS annual report (which I found out about from