Jules Janick, professor of horticulture at Purdue, wrote a wonderfully informative and entertaining brief history of giant pumpkins in last September’s Chronica Horticulturae (it starts on page 16). Regular competitions have been going on in the US since 1900, arising from state agricultural fairs.

The giant round orange phenotypes of C. maxima appear to be in a narrow gene pool out of “Atlantic Giant” (oblong phenotypes are called “Dill’s Atlantic Giant” developed by William Dill, a Canadian from Nova Scotia, Canada)… “Atlantic Giant” and related huge show pumpkins trace their origin to the cultivar “Mammoth,” recorded in the seed trade as far back as 1834…

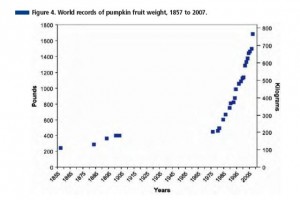

Despite this narrow genepool, the genetic gains have been phenomenal (although of course cultural practices play a part too), as this graph of world records of pumpkin fruit weight from 1857 to 2007 shows:

The current mark stands at almost 800 kg. Seed of top specimens changes hands at huge prices (up to $850 for a single seed). Prof. Janick suggests that horticultural science has ignored this record of success.

Someone has accused academics in the agricultural arena of merely proving that the practices achieved by the best growers are correct. I suggest the academic and scientific community cooperate on this engaging problem for the delight of the public everywhere.