I do hope the English dormouse population takes off. Because then the Brits could start eating the cute little things again.

Turkey to get yet another genebank?

The news that a genebank will be built in Ankara in 2009, which we nibbled a couple of days ago, is problematic for a number of reasons. But let’s just deal with an error of fact first.

The ministry announced that it will set up Turkey’s first seed bank in Ankara in 2009. The bank, which will reportedly be named Noah’s Bin, will be the fourth largest of its kind in the world.

This will not in fact be Turkey’s first seed bank, as even a Turkish tourism site knows. 1 The Aegean Agricultural Research Institute (AARI) at Izmir has in fact housed a genebank since 1964, and contributes data to EURISCO, and thence Genesys, to the tune of some 13,000 accessions.

Am I missing something? Is the Izmir genebank going to close, in favour of a larger, newer facility in Ankara? If that is the case, it will not just contain Turkish material.

Some 160,000 wheat types and 27,000 maize types currently registered at the International Wheat and Maize Improvement Center (CIMMYT) will also be included in the gene bank. Turkey will be the third country to have such a center.

What is the metric according to which this genebank would be the third in the world? The only thing I can think of is that it would be the third place to house the CIMMYT collection, after CIMMYT itself and Svalbard. But what would be the rationale for that? Why would Turkey want to go to the expense of maintaining a triplicate of “160,000 wheat types and 27,000 maize types” when it could just get the ones it wanted from CIMMYT at any time at the drop of an email?

It is very laudable that the Turkish government is taking the threat of climate change to agriculture so seriously as to contemplate an expense of this magnitude on ex situ conservation, but the article does raise some interesting questions.

Nebamun redux

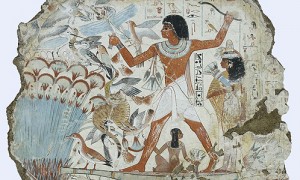

One — or at least part of one — of the great agrobiodiversity-themed art works of the ancient world is back. Apart from “Fowling in the marshes,” reproduced below, Nebamun’s painted tomb includes representations of a garden pool, wine-making, and food offerings.

Photograph: The British Museum

Yes we have orange bananas

We’ve nibbled the new New Agriculturist but not highlighted specifically, I think, the fact that it has a special on bananas. And African bananas in particular. Coincidentally, there’s a paper out in Food Chemistry on genetic variability in carotenoid content within Musa .

Featured coment: rice pests

Yolanda on rice pests:

[T]he real subsidy to biological control in irrigated rice comes from the water! The timing of all of it is also quite remarkable. The flooding cues the aquatic insects to molt into adults. This results in a outward migration of adults that emerge out of the water. The spiders use the rice plants as fishing places, trying to capture as much of the emerging aquatic insects.

Fascinating discussion.