The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), led by Olivier De Schutter, former UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, released its findings today in a report entitled ‘From Uniformity to Diversity: A paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems.’ The report was launched at the Trondheim Biodiversity Conference (Norway) by lead author Emile Frison, former Director General of Bioversity International.

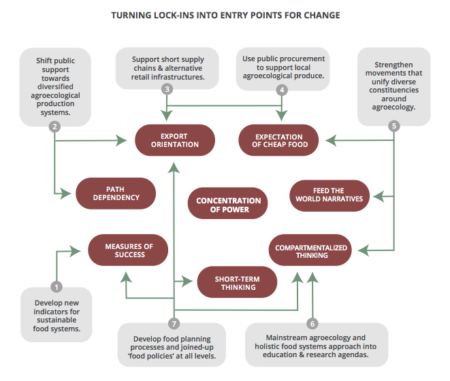

I guess you all saw that last week. There’s an executive summary. And key messages. If you don’t have the time to wade through the 100 pages of the full report. But actually the message can be summarized even further: agroecology, everywhere. And there’s a handy diagram for how to get us there:

And even that can be summarized. It’s all down to the right indicators, getting away from the tyranny of kilograms of cereals per unit land area. Measure things that are more important to people, and in ways that take proper account of sustainability, and you can’t help but produce a shift to agroecological production, the report seems to suggest.

Which is of course something we have occasionally suggested here. Well, at least the first part of that statement is something we’ve said. Not least in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals. Which reminds me to link to CIAT’s latest policy brief on progress towards defining indicators for Target 2.5, also out last week.

As the SDGs, CBD Strategic Plan for Biodiversity, and other global agreements struggle to find tangible indicators for achieving their stated targets, we propose that the results of our global analysis of crop wild relatives can be directly used to assess the current state of conservation of these wild species ex situ. Moreover, the methods used in the “gap analysis” can be adapted for assessments of crop landraces and livestock breeds. Furthermore, the tools can be used iteratively to assess progress over time.

There’s nothing in the IPES report on the SDGs in general (which I found strange, but anyway), let alone Target 2.5 specifically, but I am somewhat heartened by this passage (p. 71):

Support for diversity fairs, community genebanks and seed banks is likely to be a crucial element in strengthening social movements and unifying them around diversified, agroecological systems.

It could, I suppose be read as excluding “formal” genebanks from the equation, but I choose to interpret it as saying that national and international genebanks need to work together with community-level efforts to conserve and use crop diversity. Which I’d buy even if the calculus did not lead inexorably to agroecology, everywhere.

Amen to your last paragraph. But this Frison et al. report is a shocker. It is a severe critique of all modern farming, crop and animal production both, coupled with a failing – indeed fatuous – attempt to replace food production with an ill-defined and highly questionable concept of ‘diversified agroecological systems’. There is no mention of plant breeding except, you can guess, `participatory plant breeding’ (once). We can close down the genebanks and formal plant breeding and food exports – farmers can do the lot and eat well.

Try this key message from the report on the value of diversity: “Mixtures have also been shown to produce 1.7 times more harvested biomass on average than single species monocultures and to be 79% more productive than the average monoculture (Cardinale et al., 2008).” (p. 31, also Fig. 8). [The Cardinale paper in their bibliography is actually not 2008 but 2007 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0709069104)] This quotation is unacceptable cherry-picking: in fact the Cardinale et al. meta-review endorses monocultures, as follows: “…mixtures of species produce an average of 1.7 times more biomass than species monocultures and are more productive than the average monoculture in 79% of all experiments. However, in only 12% of all experiments do diverse polycultures achieve greater biomass than their single most productive species.” Cardinale et al. repeat this information seven times and then spend most of the rest of their paper in attempting to explain this apparent paradox.

Let me further add emphasis: in fact, in 88% of experiments, the single most productive species equals or outperforms species mixtures. After ten thousand years of experience it seems that farmers growing monocultures are doing the right thing (as real ecologists know), relying on their selection of productive species to be grown in monocultures. It also seems that the panel of estimable people who produced this report are, by deliberately ignoring this vital information, chasing moonbeams.

Cardinale et al. conclude: “Even so, our best statistical estimates suggest that it takes ≈ 1,750 days before the most diverse polyculture begins to yield more biomass than the highest monoculture.” So the general relevance of diverse polycultures to the annual cropping that produces most of our food is precisely zero.

One more example of wishful thinking: the Frison et al. (p. 62) report claims that the IAASTD (2009) report “… strongly encouraged the development of agroecological science and practice.” It did no such thing. Mentions of `agroecology’ in the IAASTD series of regional reports are very highly skewed. The results are, for Sub-Saharan Africa, 2 mentions; Central and West Asia and North Africa, 2; North America and Europe, 2; East and South Asia and the Pacific, 8; Latin America and the Caribbean, 151; and the final IAASTD Synthesis Report 22 mentions. Yet more cherry-picking of `facts’.

What are these people doing, sitting in developed countries and giving bad advice to politicians and farmers in the Global South?

Hi Dave:

Maybe I’m reading something in that I shouldn’t, but I’m wondering about your take on participatory plant breeding. If you have a minute could you expand on where you’re coming from in your first paragraph.

Thanks

Hi Clem: I worked for several years as a collector of traditional varieties and know and respect farmers’ ability to manage their crop varieties. As a result, I am totally in favour of participatory plant breeding but only as part of the toolbox of crop improvement that includes formal plant breeding and the use of all the variation to be found in genebanks. The `toolbox’ approach is absent from the Frison et al. report, as it dismisses, to the point of pastiche, a large part of farming globally (and formal plant breeding and indeed genebanks).

In my experience, traditional farmers go to great lengths to access new variation in their crops. I think this is a result of the lack (or erosion) of high levels of `local adaptation’ in their crops, commonly regarded by farmers as their varieties getting `tired’ and needing replacement. Agroecology seems to believe in varieties getting more locally adapted and therefore `better’: not so (as with many other agroecological beliefs).

Local adaptation may not even be true for the wild flora, never mind the more transient crop varieties, as described by a proper biologist: “Thus the first-order rationale for preferring native plants—that, as locally evolved, they are best adapted—cannot be sustained. I strongly suspect that a large majority of well-adapted natives could be supplanted by some exotic form that has never experienced the immediate habitat. In Darwinian terms, this exotic would be better adapted than the native…” Gould, S.J. (1997) An evolutionary perspective on strengths, fallacies, and confusions in the concept of native plants. In: Wolschke-Bulmahn, J. (ed) Nature and Ideology: Natural Garden Design in the Twentieth Century, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC, USA, pp. 11–19.

Thanks Dave,

I too hear from U.S. based farmers about varieties getting ‘tired’ over time (I’m thinking of monocultures of wide expanse like corn and soybean in the US Midwest). To me there seem to be two principle reasons for this observation: over time the local pathogen population would adapt to varieties used widely and repeatedly, and as newer varieties with better yields become available the older varieties will appear less productive by comparison (tired). Better yields in newer varieties (or hybrids) can be achieved with different genes for resistance or tolerance to the present pathogen complex with the effect that a new variety then imitates an ‘exotic’ within a ecosystem ‘trained’ on a different host of the same species. Agronomic practices [planting date, row spacing, plant population, pesticide use (timing, specific active ingredients, etc), tillage regime] will also impact the micro environment that varieties perform in. ‘Tired’ then begins to encompass too broad a spectrum of causes.

I also like your ‘tool-box’ metaphor. Having several different ways to approach an issue allows us flexibility we can employ to offset or ameliorate the degree to which challenges will limit future success.