Rhizowen offers Rome’s garden guerillas a choice target:

I’ve always felt that the Terme di Caracalla were missing something. Sunflowers.

A little too far away to look after them, but you never know …

Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog

Agrobiodiversity is crops, livestock, foodways, microbes, pollinators, wild relatives …

Rhizowen offers Rome’s garden guerillas a choice target:

I’ve always felt that the Terme di Caracalla were missing something. Sunflowers.

A little too far away to look after them, but you never know …

There’s something satisfying about a bunch of guerilla gardeners unilaterally declaring 1 May to be International Sunflower Guerilla Gardening Day. Not for them the stuffy business of official approval and endless process. Just go ahead and do it. Today!

Alas, the process of informing people who might be interested seems also to be an ignored part of the process. Or maybe it’s just us. Anyway, unprepared for an actual act of guerilla gardening, I instead dedicated myself to transplanting half a dozen Black Magic sunflower seedlings. Maybe when they’re a bit bigger and sturdier I’ll consider sending a couple off to fight the good fight. And they are wild relatives.

Before:

After:

Here’s a time-lapse video of the long-term continuous-cropping experiment at IRRI. I didn’t dare turn the music off in case someone was going to tell me something interesting about it all. They didn’t, which makes it just interesting eye-candy. In my opinion, the video would also benefit if it gave some sense of the passing of real time — maybe an animated timeline?

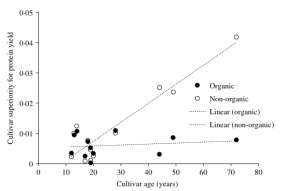

![]() One of the arguments in the organic-can-feed-the-world oh-no-it-can’t ding dong is about the total yield of organic versus non-organic. 1 Organic yields are generally lower. One reason might be that, with a few exceptions, mainstream commercial and public-good breeders do not regard organic agriculture as a market worth serving. The increase in yield of, say, wheat over the past 70-80 years, which has been pretty profound, has seen changes in both agronomic practices — autumn sowing, simple fertilizers, weed control — and a steady stream of new varieties, each of which has to prove itself better to gain acceptance. Organic yields have not increased nearly as much. A new paper by H.E. Jones and colleagues compares cultivars of different ages under organic and non-organic systems, and concludes that modern varieties simply aren’t suited to organic systems. 2

One of the arguments in the organic-can-feed-the-world oh-no-it-can’t ding dong is about the total yield of organic versus non-organic. 1 Organic yields are generally lower. One reason might be that, with a few exceptions, mainstream commercial and public-good breeders do not regard organic agriculture as a market worth serving. The increase in yield of, say, wheat over the past 70-80 years, which has been pretty profound, has seen changes in both agronomic practices — autumn sowing, simple fertilizers, weed control — and a steady stream of new varieties, each of which has to prove itself better to gain acceptance. Organic yields have not increased nearly as much. A new paper by H.E. Jones and colleagues compares cultivars of different ages under organic and non-organic systems, and concludes that modern varieties simply aren’t suited to organic systems. 2

The basics of the experiment are reasonably simple. Take a series of wheat varieties released at different dates, from 1934 to 2000. Plant them in trial plots on two organic and two non-organic farms for three successive seasons, measure the bejasus out of everything, and see what emerges. One of the more interesting measures is called the Cultivar superiority (CS), which assesses how good that variety is compared to the best variety over the various seasons. As the authors explain, “A low CS value indicates a cultivar that has high and stable performance”. The expectation is that a modern variety will have a lower CS than an older variety, and for non-organic sites, this is true. At organic sites, the correlation is much weaker.

You can see that in the figure left (click to enlarge). For the open circles (non-organic) more modern varieties have lower CS (higher, more stable yield), while for filled circles (organic) there is no relationship. Why should this be so. Because of those changes in agronomic practices mentioned above.

You can see that in the figure left (click to enlarge). For the open circles (non-organic) more modern varieties have lower CS (higher, more stable yield), while for filled circles (organic) there is no relationship. Why should this be so. Because of those changes in agronomic practices mentioned above.

[M]odern cultivars are selected to benefit from later nitrogen (N) availability which includes the spring nitrogen applications tailored to coincide with peak crop demand. Under organic management, N release is largely based on the breakdown of fertility-building crops incorporated (ploughed-in) in the previous autumn. The release of nutrients from these residues is dependent on the soil conditions, which includes temperature and microbial populations, in addition to the potential leaching effect of high winter rainfall in the UK. In organic cereal crops, early resource capture is a major advantage for maximizing the utilization of nutrients from residue breakdown.

To perform well under organic conditions, varieties need to get a fast start, to outcompete weeds, and they need to be good at getting nitrogen from the soil early on in their growth. Organic farmers tend to use older varieties, in part because they possess those qualities. Concerted selection for the kinds of qualities that benefit plants under organic conditions, which tend to be much more variable from place to place and season to season, could improve the yileds from organic farms.

In our line of work it is common to hear people rave about the importance of informal seed systems for ensuring that farmers have access to the agricultural biodiversity they need and want — in developing countries. Not so common elsewhere. Now, from the Ethicurean, comes news of a project to build a Backyard Seed Vault, which sounds very like an informal seed system in San Francisco, California. The project’s instigator, who is co-executive director of a group called Agrariana (and check out their origins and mission statement), has this to say:

We’re looking for approximately 100 San Francisco Bay Area gardeners for the inaugural season who would like to work as a community to save heirloom vegetable seed. … Agrariana will lead hands-on workshops in participants’ gardens on properly saving seed. The Backyard Seed Vault is working in conjunction with the Bay Area Seed Interchange Library (BASIL), a project of the Ecology Center, for their immense knowledge on properly saving, labeling, cataloging, and storing seeds. Seeds not redistributed to participants will be donated to BASIL, providing an opportunity for any community member to “check out” seed to grow in their gardens. Gardeners of all skill levels are welcome to participate.

Sounds like a lot of fun. And there are actually lots of similar seed exchanges all over Europe, North America, Australia etc etc. Will they, I wonder, ever attract the attention of people who study the value of informal seed networks elsewhere?