You collect leaves from 220 walnut trees of two morphologically very distinct species (Juglans regia and J. sigillata) from two unrelated groups of families of villagers in each of six different villages in Tibet. You get the gene-jockeys to do their microsatellite stuff on the leaves. You calculate the contribution of species, of the kin relationship of the growers and of village to genetic diversity. You expect the biggest genetic differences to be between species.

You are wrong.

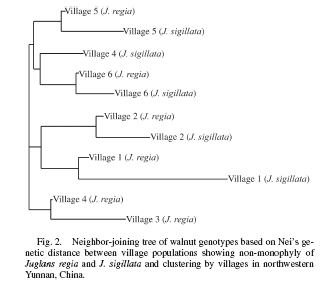

Yes, the “species,” which look totally different, are in fact indistinguishable genetically. But there were significant differences among villages, and smaller but still significant differences between unrelated families of farmers within villages. So, you might be particularly interested in certain traits, for improvement say (and so are the farmers: walnut landraces in this part of Tibet are often named after fruit phenotypes). But — in this case — morphology is not a great guide to the totality of the underlying genetic diversity. So you can’t use it alone for conservation.

Which is also the conclusion researchers in Benin arrived at in their study of another tree, akee (Blighia sapida), also just out. A conservation and use (domestication, in this case) strategy “should target not only the morphotypes recognized by local populations but should also integrate the population genetics information.”

Does this amount to a general rule?