- Maize geneticist and forage breeder among USDA’s Agricultural Research Service Scientist of the Year winners.

- BBC man lands top Kew job.

- Elinor Ostrom RIP.

- If the wormwood don’t get you, the groundsel will. A tale of two wild Asteraceae.

- Foxtail Millet Offers Clues for Assembling the Switchgrass Genome. So that’s what millet is good for.

Nibbles: Big cheese, Perennials, Maize, Plant breeding, Tiny corn, Communicators, Traditional Foods, Forest peoples, Guar

- IFAD’s organic Moldovan cheese wins big.

- Advice for Rwandan coffee and banana farmers to cope with climate change.

- Advice from Mexico’s campesinos on how to cope with climate change.

- Do they – or you – need to participate in plant breeding? This toolkit could help.

- These folks don’t … From little corn plants, big efficiencies grow. I think.

- Newly trained press officers to support agriculture on Indian Ocean islands.

- Hurrah! A conference on traditional foods, with street food seminar accompaniment. h/t CFF.

- The diversity of forest peoples, united in their dependence on forests.

- Alternatives to guar: “Even though all the ingredients are acquired from food suppliers, the CleanStim fluid system should not be considered edible.”

Brainfood: Barcoding, DArT for beans, SNOPs for Cacao, Aquaculture impacts, Cassava GS, Cereals in genebanks, Symbiosis

- A critical review on the utility of DNA barcoding in biodiversity conservation. Not bad, but not by itself.

- A whole genome DArT assay to assess germplasm collection diversity in common beans. It works, and can distinguish Andean from Mesoamerican accessions.

- Optimization of a SNP assay for genotyping Theobroma cacao under field conditions. It works, and is being used in Ghana.

- A Global Assessment of Salmon Aquaculture Impacts on Wild Salmonids. Meta-analysis shows farming salmon and trout in an area has in general been bad for their wild relatives there.

- Genome-wide selection in cassava. High correlations between SNPs and several phenotypic traits of interest to breeders mean that selection time could be cut by half. Could.

- Cereal landraces genetic resources in worldwide GeneBanks. A review. We don’t have enough data. On so many different levels.

- Coevolutionary genetic variation in the legume-rhizobium transcriptome. Wait, does this mean we should be conserving Rhizobium too?

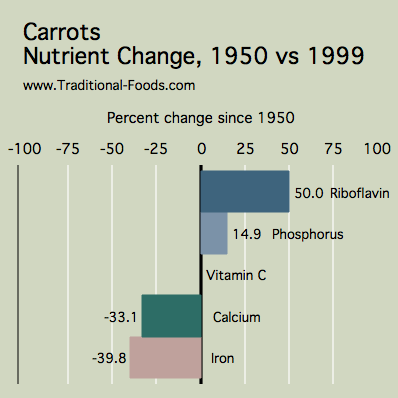

Nutrients are declining in modern varieties

The internet has been a bit a-flutter recently on the subject of declining nutrients, particularly in fruit and veg. We nibbled as much a week or so ago, and I asked whether the data had been published. 1 Indeed it had, as Amanda Rose graciously pointed out. As for reasons, Amanda said:

An editor of Organic Gardening magazine suggested that use of chemical fertilizers and subsequent decline in soil minerals was the cause. A peer reviewed study of the data provides another explanation: commercial cultivation of seed has traded nutrient density for yield, pest resistance, and transportability, factors critical to the commercial success of any crop.

Off, then, to the peer reviewed study. The best I can say is: it’s complex. Don Davis, of the University of Texas, and his colleagues used existing USDA data on the nutrient content of 43 garden crops, mostly vegetables, to compare quantities from the 1950 edition of the USDA’s “Composition of Foods” with those in the 1999 edition. Many pitfalls await the unwary in such an exercise, not least of which is the lack of basic information about some of the sample sizes and distribution of the results. Davis and his colleagues seem to have thought of them all, and worked round them as far as possible in various ways. 2 In essence, Davis et. al compare median values in 1950 with medians in 1999; less than 1 represents a decrease, more than 1 an increase. And the bottom line:

As a group, the 43 foods show apparent, statistically reliable declines (R < 1) for 6 nutrients (protein, Ca, P, Fe, riboflavin and ascorbic acid), but no statistically reliable changes for 7 other nutrients. Declines in the medians range from 6% for protein to 38% for riboflavin. When evaluated for individual foods and nutrients, R-values are usually not distinguishable from 1 with current data. Depending on whether we use low or high estimates of the 1950 SEs, respectively 33% or 20% of the apparent R-values differ reliably from 1. Significantly, about 28% of these R-values exceed 1.

That needs unpacking. First, there’s the question of “apparent” declines. Davis points out that while his statistical approaches eliminate random uncertainties, it is always possible to postulate a systematic error affecting any particular nutrient in either direction. Iron, for example, is tens of thousands of times more abundant in soil than in crops; merely changing the way samples are washed, to remove more soil in the 1999 samples, would result in a large decrease in iron.

That is why I call these R values “apparent”.

But there’s a kicker:

However, it would seem scarcely credible to attribute all the statistically significant median R < 1 to multiple systematic errors, each one operating in only one direction.

So the overall decline, considering all the crops and all the nutrients, is real enough, even though for each crop and each nutrient most of the differences (between 67% and 80%) are not statistically significant.

Some nutrients did increase, most notably vitamin A and riboflavin. Which makes it plenty delicious that in all the fluttering about declining nutrients, Scientific American (no less) chose to major on carrots, 3 and to blame it all on “soil depletion”.

You mean it isn’t soil depletion?

Davis comes down firmly against the “organic” idea that “chemical fertilizers and subsequent decline in soil minerals” is the problem. The fact that some nutrients definitely increased, coupled with the observation that protein (mostly nitrogen, N), phosphorus (P) and ash (mostly potassium, K) each declined from 1950 to 1999 – despite the fact that “chemical fertilizers” are largely N, P and K – puts paid to that idea.

Instead, Davis et al. focus on two different “dilution” effects. Environmental dilution is an idea that has been around a while. In essence, plants in well-fertilized, well-watered soil grow larger but take up the same total nutrients. So the nutrients are spread through a larger crop, giving a lower concentration per gram of dry matter.

Davis also identified another effect that he called genetic dilution. The bulk of the dry weight yield of most fruits, vegetables and grains is carbohydrate. When breeders select for high yield, they are effectively selecting for high carbohydrates …

… with no assurance that dozens of other nutrients and thousands of phytochemicals will all increase in proportion to yield. Thus, genetic dilution effects seem unsurprising.

The best evidence for genetic dilution comes from contemporary studies in which a time-series of varieties is grown side by side, eliminating all the problems of historical data, agronomic practices, etc etc. Davis cites a few such studies, and more are being published. In general, they do show declines in nutrient density, which can be ascribed to breeder selection.

So what about the question Luigi posed a while back? Is modern plant breeding bad for your health? Possibly, a little, but not in the way most people think. The big problem isn’t that nutrients in fruit and vegetables have decreased; despite the decline, they remain among the most nutrient dense foods you can eat. So eat them. Choosing one growing regime rather than another isn’t going to make any difference. The big problem is that we’re still eating too little fruit and veg and too much refined staples. Last word to Don Davis:

Our findings give one more reason to eat more vegetables and fruits, because for nearly all nutrients they remain our most nutrient-dense foods. Our findings also give one more reason to eat fewer refined foods (added sugars, added fats and oils, and white flour and rice), because their refining causes much deeper and broader nutrient losses than the declines we find for garden crops.

Technology should allow us to increase selected nutrient concentrations. 4 But will we learn 20 or 40 years later that there were new, unintended side effects? Another question looms large: Is it wise, in the era of technology, to keep crop size (or even the concentrations of a few, selected nutrients) as our primary measure of farming success?

Nibbles: Aquatic mapping, Biofortified millet, Indian agriculture, African agriculture, Restoration, Online flora, Farm Bill, Right to Food, Elk farming, Forestry fellowship, Breadfruit, Foods and climate change

- OBIS maps marine organisms. But does it include this data from China?

- Private sector delivers biofortified millet. But will it make it to the wiki for Indian agriculture?

- New paper by APRODEV and PELUM on why CAADP should follow IAASTD. Glossary not included. And more on African agriculture from Gates. Not like this, though.

- Millennium Seed Bank in ecosystem restoration. And a study on ecosystems that are actually going to require less restoration than others.

- Monsanto supports online world flora. What could possibly go wrong? Meanwhile, in the public sector…

- Olivier de Schutter’s recent Right to Food shpiel for IFPRI. LOTS of words. I guess you had to be there.

- Small-scale elk farming primer. Not as crazy as it sounds, but pretty crazy.

- And if you’re a young scientist, from sub-Saharan Africa, and interested in forest genetic resources, well, here’s a fine forestry fellowship opportunity.

- The Bounty Redux. The whole bringing-breadfruit-to-the Caribbean thing seems to be going more smoothly this time.

- Huffington slideshow on the world’s endangered foods.