It’s a bit apocalyptic in tone, but it’s always good to see a genebank featured (starting at about 7:00 minutes in) in a popular documentary, in this case IRRI’s. But there’s much more, so watch the whole thing. Well done, Ruaraidh. And thanks, History Channel.

Nibbles: Barley, Fellowship, Supplier, Malnutrition, choices, Rice and climate change

- “[A]n ancient barley grain”. Just the one. One only. From Neolithic England.

- Crawford Fund Fellowship “for an agricultural scientist from a selected group of developing countries whose work has shown significant potential”.

- New World Seeds & Tubers, a supplier thereof.

- Alternative remedies for late potato blight.

- Mild underweight a better indicator of childhood malnutrition than severe. Press release and paper.

- “Food or the environment? Mixed signals confuse farmers.” There has to be a choice?

- Indonesia sorts out its rice-adapted-to-climate-change problem.

Saying goodbye to a maverick

The distinguished agricultural journalist Tom Hargrove died a few days ago. A contributor to a closed mailing list noted that he had made “a stellar scientific contribution to the CGIAR” in particular, though his renown went far beyond that. Very true. All the more so as he was one of the first to question the wisdom “of growing genetically uniform varieties over millions of hectares…from within the ‘lions den’ where the dogma was gospel.” Perhaps his greatest legacy is that the dogma is not as entrenched as it was.

Getting curators to think like breeders

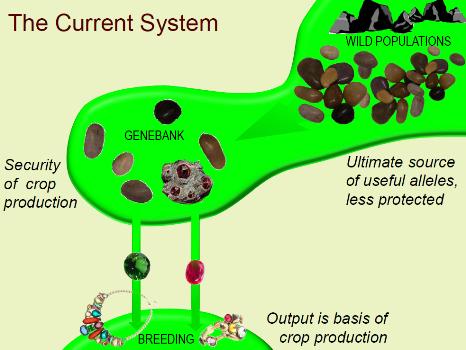

The presentation on genomics and fruit genebanks Cameron Peace gave at the recent PAG symposium deserved more than the nibble we gave it. Dr Peace, who is an assistant professor in tree fruit genetics at Washington State University, is advocating nothing less than a complete change in the mindset of genebank curators. Here’s how he characterizes the current system:

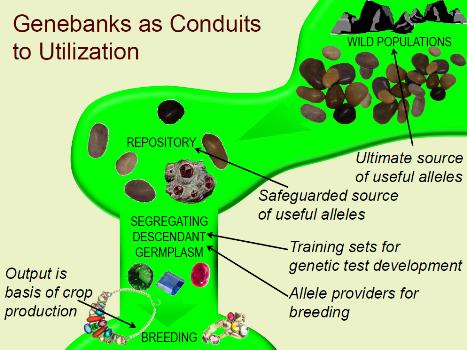

Notice the mere trickle of material from the genebank to the user. All too true. I would say that there is also much less movement of material from wild populations to genebanks than is suggested by the diagram. But that’s at least partially down to the fundamental fact that flow of material to breeders is fairly limited. No demand, no supply. This, in contrast, is what Dr Peace wants to see:

He wants genebanks to get their skates on and, to mix a metaphor, not wait for the breeders to pull. He wants them to push. He wants them to provide performance information, and not just data on morphological descriptors; performance-predictive DNA information, and not just genetic diversity data; segregating descendant populations, and not just landraces or wild populations.

In essence, Dr Peace wants genebank curators to think like breeders. More, he wants them to be breeders. Or at least pre-breeders.

There’s much to be said for this. The latest State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOW2) bemoans the continuing obstacles to use of collections. Something Must Be Done, it suggests. But curators have their hands full. The same SOW2 says that they have no money. That they need more equipment. That they have regeneration backlogs. That people are telling them to conserve more neglected and underutilized plants, and more crop wild relatives. That’s when armed gangs of looters are not ransacking their facilities. Now they should be plant breeders as well? Sheesh!

Well, the fact is that with the International Treaty on PGRFA, most curators don’t have to worry about basic conservation. Not really. Not for Annex 1 crops anyway. They can choose to outsource that stuff, for example to the international centres of the CGIAR, secure in the knowledge that they can have access to the material whenever they want it.

With the ITPGRFA, curators have the space to think like breeders. But do they have the training? And will the breeders return the compliment, and think a bit like curators?

Seed dispersal: how far is far enough?

![]() This barely merits the Research Blogging tag, because all I want to do here is raise a possibility, and a tenuous one at that. I confess that I was attracted in a high-speed scan of headlines, by this one: Leaving home ain’t easy: non-local seed dispersal is only evolutionarily stable in highly unpredictable environments. 1 The starting point is the common armchair argument that seeds disperse for three non-exclusive reasons: to escape changes in the environment they are leaving, to avoid overcrowding (and competition with sibs?) and to find and exploit new environments before other competitors.

This barely merits the Research Blogging tag, because all I want to do here is raise a possibility, and a tenuous one at that. I confess that I was attracted in a high-speed scan of headlines, by this one: Leaving home ain’t easy: non-local seed dispersal is only evolutionarily stable in highly unpredictable environments. 1 The starting point is the common armchair argument that seeds disperse for three non-exclusive reasons: to escape changes in the environment they are leaving, to avoid overcrowding (and competition with sibs?) and to find and exploit new environments before other competitors.

Robin Snyder’s mathematical model seeks to understand how far seeds need to move from their parent to be reasonably certain of encountering different growing conditions. After all, “why ‘escape in space’ only to land somewhere more or less like where they started?” The models show that in almost all cases, dispersal tends to be not far enough to get away from the “parental” conditions. Only when favourable conditions are very fleeting is it worthwhile for some seeds to leave home far behind, as a “response to environmental unpredictability”.

Why bring this up here? Because the seeds of high-performing agricultural varieties are often dispersed hundreds or thousands of kilometres from the environments in which they were deemed successful. In theory they are being sent to places with very similar growing environments. But might this actually be an argument for sending seeds far from home specifically as a strategy to enable the farmers selecting them to respond to environmental unpredictability?