Jamon iberico finally gets a visa.

Ancient brewing

Puebloans and ancient Irish brewed beer. Pass the bottle.

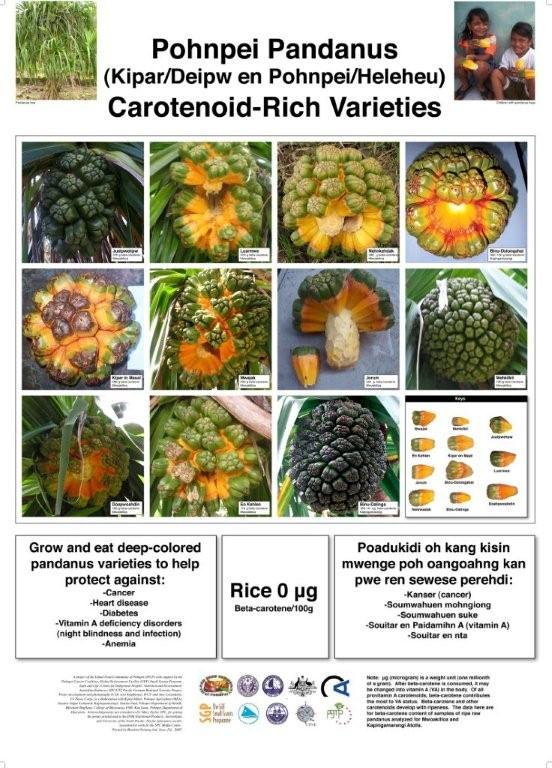

New pandanus poster from Pohnpei

Dr Lois Englberger of the NGO Island Food Community of Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia has just announced the release of a colorful new local food poster entitled “Pohnpei Pandanus: Carotenoid-rich Varieties.”Â

Photographs and nutrient content of nine varieties of pandanus from Mwoakilloa Atoll and two varieties from Kapingamarangi Atoll are presented, along with the message that these carotenoid-rich foods can help protect against cancer, heart disease, diabetes, vitamin A deficiency and anemia or weak blood.Â

The development of the poster started in 2003 with the collection of samples and arranging for analysis for provitamin A and other carotenoids, including beta-carotene, the most important of the provitamin A carotenoids. Note that rice contains no carotenoids.

We hope that this poster may help to promote this neglected food crop, to raise awareness about the distinct varieties of pandanus and to increase understanding about the important health benefits that may be obtained by consuming this fruit.

Warm thanks are extended to the Pohnpei Cancer Coalition, Global Environmental Facility Small Grant Program, Sight and Life, Center for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment, Australian Embassy, SPC GTZ Pacific German Regional Forestry Program, Pohnpei Agriculture, Pohnpei Departments of Health and Education, and the College of Micronesia-FSM for funding and other support, to the Secretariat of the Pacific Community in Suva, Fiji, for assistance in getting the poster developed, printed and laminated, and to all those assisting in this project.

Mopane worms

Mopane worms:Â a traditional source of protein in Botswana. I’ve tried them. They’re yummie.

Tasty rice

I’m at IRRI in the Philippines the whole week (and the next, actually, but that’s another story) for a workshop to develop a global ex situ conservation strategy for rice genetic resources. More on that later. Right now, I just wanted to show you a photo I took today during a rice variety tasting the T.T. Chang Genetic Resources Centre laid on. There were about 20 different genotypes from around the world: normal and fragrant, white and black, loose and very sticky. They included Carolina Gold, which I blogged about a few days ago. It’s amazing how different rice varieties can taste.