- Conserving dambos for livelihoods in southern Africa. How many CWRs are found in such wetland habitats around the world, I wonder.

- Cucumis not out of Africa.

- Exploring “the connection between traditional knowledge of herbs, edible and medicinal plants and media networked culture.” And why not.

- PBS video on malnutrition.

- Fungal exhibition at RBG Edinburgh.

- Indian Council on Agricultural Research framing guidelines for private-public partnerships in seed sector. That’ll stop the GM seed pirates.

- Conserve African humpless cattle! They’re needed for breeding.

- UG99 — and crop wild relatives — in the news. The proper news. The one people pay attention to.

- Vanilla lovers better start stocking up.

- Kenyan farmers earning money selling sorghum to brewers. What’s not to like.

Nibbles: Breeding, Art, Bison, Pumpkin seeds, Sweet potato, Bambara groundnut, Carnival

- Cary Fowler on the need to breed.

- MRIs of fruits and vegetables. Well, why not?

- The genetic consequences of bovine inter-specific sex explained. SFW.

- How Mrs Joséphine Enoce Bouanga makes milk from squash seeds in Pointe-Noire.

- Gates Foundation orange sweet potato project in Mozambique. Still waiting to hear what they’re going to do with all those useless landraces they’ll be replacing.

- Nourishing the Future does Lost Crops of Africa 101. Beginners, start there, but don’t expect to be taken anywhere interesting.

- Blog carnival Scientia Pro Publica #35 is up, but what’s with the verse alphabetical order? Harummph.

Nibbles: Oil palm, Breadfruit, Barcoding, Guyana genebank, Wheat and heat

- Palmhugger, an oilpalm advocacy group, likens Greenpeace to Goebbels. Who are they really? CIFOR is linking to them on Facebook, so they’re probably kosher, right?

- Nice story on breadfruit in Hawaii.

- More barcoding stuff.

- Reader: We must have a bank of seeds of our fruits and vegetables. Minister of Agriculture: We do!

- Australian wheat boffins: “Adaptation strategies need to be considered now to prevent substantial yield losses in wheat from increasing future heat stress.”

The horse in Mongolian culture

They may be trying to develop and diversify their agriculture now (well, since the 1950s), but Mongolians are traditionally very much a nomadic herding culture, with the horse at its centre. 1 One expression of that is how early kids learn to ride.

They may be trying to develop and diversify their agriculture now (well, since the 1950s), but Mongolians are traditionally very much a nomadic herding culture, with the horse at its centre. 1 One expression of that is how early kids learn to ride.

Most young Mongolians — boys in particular — learn to ride from a very young age. They will then help their fathers with the herding of goats, sheep and horses. Some children have a chance to ride at festivals called Naadam — the biggest of which is held on 11th-13th July in Ulaanbaatar — though there are naadams held throughout the year all over the countryside. Young jockeys between the age of 5 and 12 (girls and boys) race horses over distances ranging from 15km to 30km. There are 6 categories for the races depending on the horses’ age, including a category for 1 year old horses (daag) and one for stallions (azarag).

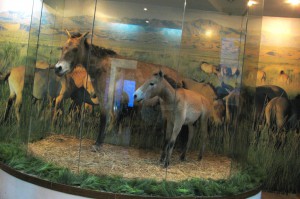

Alas, this museum display is as close as I got to seeing the famous Mongolian Wild Horse or Przewalski’s Horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), locally known as takhi.

It’s possibly the “closest living wild relative of the domesticated horse, Equus caballus.” Certainly it is genetically very close to the local domesticated breed based on molecular markers, though that could be because of interbreeding. Last seen in the wild in 1969, its restoration in China and Mongolia from captive stock, for example to the Hustain Nuruu National Conservation Park, is one of the great conservation success stories.

How many varieties are there in the world, mom?

Back at the day job, we are often asked by journalists and others how many different types, or varieties, of this or that crop there are in a country, or indeed the world. And, with help from our friendly crop experts, we have tried to provide answers. But it is as well to remind ourselves sometimes how slippery the question is. Because, to paraphrase Bill Clinton, it really does depend on what your definitions of “different” and “variety” are. For example, take rice in a particular part of Thailand, as the authors of a recent paper in GRACE did. 2

They looked at 20 accessions of a single landrace, defined as a “geographically and ecologically distinctive population, identifiable by unique morphologies and well-established local name.” That is, these 20 samples, though collected from different farmers and even villages, all basically looked the same, and were recognized as belonging to the same type by farmers, who gave them all the same name — Muey Nawng.

But the authors found significant, non-random, patterned variation within the material, not only in microsatellite markers, which wouldn’t perhaps be so bad, but also in endosperm starch type, days to heading and, interestingly, gall midge resistance. So how many varieties were there among the 20 samples of Muey Nawng? Answers on a postcard, please.