- DNA survey of African village dogs reveals as much diversity as in East Asian village dogs, undermines current ideas about where domestication took place.

- Fossil doubles age of dog domestication.

- “When children felt like buying candy, they ran into their father’s fields and returned with a few grams of opium folded inside a leaf.”

- “The rice, a traditional variety called kintoman, came from my grandfather’s farm. It had an inviting aroma, tasty, puffy and sweet. Unfortunately, it is rarely planted today.”

- “An era of synthetic gums ushered in the near death of their profession, and there are only a handful of men that still make a living by passing their days in the jungle collecting chicle latex…The generational changes in this boom-and-bust lifestyle reflect a pattern that has occurred with numerous extractive economies…”

- Morocco markets prickly pear cactus products.

- TreeAid says that sustainable agriculture depends on, well, trees.

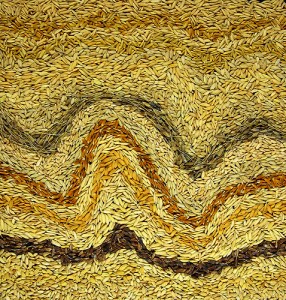

Rice diversity measured and photographed

I did a quick nibble a few days ago about the OryzaSNP project, in which “[a]n international team of investigators used microarray-based resequencing to look for SNPs in 100 million bases of non-repetitive DNA in the genomes of 20 different rice varieties and landraces.”

They’ve come up with 159,879 single nucleotide polymorphisms, a “gold-standard set of curated polymorphisms” for rice.

As for the 20 varieties used…

“[t]hese varieties, the OryzaSNPset collection, are genetically diverse and actively used in international breeding programs because of their wide range of agronomic attributes,” the authors explained.

But what do they look like? Well, I just found this photograph of their seeds on IRRI’s Flickr page. A nice idea.

Nibbles: Camel, Maya forestry, Ancient barley, Cattle diversity, Poisons, Agroforestry Congress, Lactase persistence

- Wild camel genetically distinct from the domesticated kind. Well I never.

- Maya tapped into their “sacred groves” to build temples, which did not end well.

- Boffins extract DNA from ancient barley in Upper Egypt, find it was 2-rowed, but derived from a 6-rowed ancestor. No word on whether it was used to make beer, but my guess is yes.

- Large Y chromosome microsatellite study of Eurasian cattle does “not support the recent hypothesis on the origin of Y1 from the local European hybridization of cattle with male aurochsen.” This could run and run.

- I like this idea: a garden of poisons.

- Agroforestry’s coming-of-age party coming up. You going? Let us know.

- Multiple explanations for lactase persistence.

Nibbles: India, City chicks, Rooftop gardens, Black cherry, Prairie grasses, Oryza SNP

- ICRISAT recommends diversity to cope with climate change in India.

- US urban farmers “mad as wet hens“. City chicks?

- US urban farmers with a view to die for.

- CWR becomes nuisance when free of soil pathogen.

- Convicts help with germplasm regeneration and multiplication.

- The “gold-standard set of curated polymorphisms” for rice.

Livestock genetics symposium online

DAD-Net informs us that the presentations given at the symposium on Statistical Genetics of Livestock for the Post-Genomic Era, held at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, on May 4-6, 2009, are now available online in the form of both PDFs and videos. Quite a resource.