You want a rapid gallop through what we have learned about livestock domestication from molecular markers? Here it is, courtesy of Groeneveld et al. Deep breath…

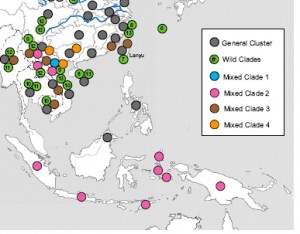

For all domestic species, mtDNA data have allowed the elucidation of the relationships with wild ancestor species, and for most species it is also informative at the intercontinental level… Sheep, goats, and taurine cattle (Bos taurus) are presumed to have been domesticated in Southwestern Asia. The Indus valley has been proposed to be the site of domestication of indicine cattle and the river type of water buffalo, while the swamp type of water buffalo is thought to have originated in the Yangtze valley. The domestication of pigs is considered to have happened across Eurasia and Eastern Asia in at least seven separate events involving both European and Asian subspecies of boar. The Yak is presumed to be the result of a single domestication event in China/Tibet with at least three maternal lineages contributing to the ancestral yak gene pool. Domestic chickens are thought to be the result of multiple domestication events, predominantly of Red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus) in Southeastern Asia and possibly also involving Gallus sonneratii and maybe Gallus lafayettii. Horses were domesticated in a broad area across the Eurasian steppe, and in this species the husbandry style has left considerable signatures. It is presumed that mares were domesticated numerous times, but that only a few stallions contributed to the genetic make-up of the domestic horse. The last finding illustrates the use of Y-chromosomal haplotypes as a marker for mammalian patrilines. This is still limited by the identification of haplotypes, but probably has the same potential as in human population genetics.

Quite a tour de force, I think you’ll agree. Read the paper itself for trenchant summaries of the results of literally dozens of molecular studies on these species, describing the relationships among breeds and geographic patterns in diversity. But if you’re just interested in the general principles, here they are:

- There is evidence of multiple domestication events for most species.

- These often involved more than one ancestor species or subspecies and

- repeated introgression events of closely related ancestor species.

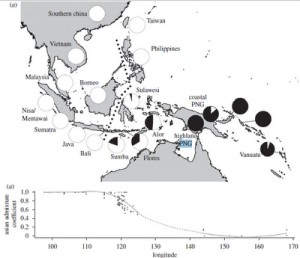

- Genetic variability declines with increasing distance from centres of domestication.

- All species show strong geographic structure in genetic diversity, except sheep.

- Most of the genetic diversity is present within a breed and not between breeds.

The most interesting thing to me is the geographic structure, and the one thing the paper doesn’t do in any great detail is compare and contrast the patterns found in the different species. I mean, are horse breeds from Iberia more distinct from other European horse breeds than its cattle breeds are from other European cattle breeds, say? And if so, why? The paper describes the patterns found in each species, but doesn’t set them side-by-side, as it were. Once someone does that, we can go on to compare them with what we know about crops…