- More either-or stuff from the Guardian on the Indian GM brijal story.

- The USDA prickly pear cactus germplasm collection gets some exposure. And how many times can one say that.

- Much better title from Discover on that ancient northern Amazonian earthworks story.

- Kenyan foresters tell people to eat bamboo. Luigi’s mother-in-law politely demurs. On the other hand, she might like this.

- Swiflet farming? Swiflet farming.

- Really heated exchange on paper on coconut lethal yellowing in Yucatan develops on Google Groups. I love the internet.

- PROTA publishes expensive book on promising African plants. Promises, promises. NASA promised us the personal jetpack. Where are we with that?

- Nice summary of that Mesoamerican agricultural origins story we blogged briefly about a few days ago. So what exactly do you call hunter-gatherers who also grow crops?

- First International Symposium on Wild Relatives of Subtropical and Temperate Fruit and Nut Crops will be held March 19-23, 2011 in Davis, California on the campus of the University of California, Davis. Book early.

Nibbles: Asses, Mapping pathogens, Oysters, Tea, Turkish biodiversity hotspot, Dolmades and sage, Yams festival, Pollen video, Agriculture and mitigation, Rarity, School feeding, Sheep

- Jeremy probes into wild asses at Vaviblog.

- Mapping the evolution of pathogens. And in kinda related news…

- The European oyster needs diversity. Well, natch.

- The tree forests of Yunnan, and, concidentally, the story of how the secret of their product got out.

- The Kaçkar Mountains at Yusufeli, northeast Turkey are in trouble. Any crop wild relatives there, among the bears and other charismatic megafauna?

- Speaking of Turkey, here’s how to make one of its delicacies. But hey, if you don’t have vine leaves, you can use this.

- Having fun with yams.

- Drori does pollen.

- FAO’s Mitigation of Climate Change in Agriculture (MICCA) Project. Any agrobiodiversity-related stuff? Need to explore…

- “…conserving species may only require specific activities, such as collect and distributing seeds.”

- African school feeding programme uses “local” products. What would Paarlberg say? You can find out here, if you have 90 minutes to spare.

- British boffins breed self-shearing sheep. No, really.

Nibbles: Rice conservation and use, Tunisian genebank, Buno, Popcorn, Sustainability, Brazilian social networking, Strawberry breeding, Sunflower genomics, Climate change and fisheries

- Lots of Indian rice in the IRRI genebank. Any of it being used to develop drought-tolerant varieties?

- Lots of journalists in the Tunisian genebank.

- How they make coffee in Ethiopia.

- How they make popcorn the world over. You sometimes get popcorn (or popped sorghum) with coffee in Ethiopia, now I think of it. And since we’re on an Ethiopian kick, fancy some enjera? Gary Nabhan did.

- “Productivity vs. sustainability is a ‘false choice.’” Well I never. And probably not news to these people either, or these. But to these guys?

- A Twitter roundup from Embrapa.

- Ugly hybrid of two wild strawberries may cause allergies.

- Explanation of evolution of doubled genes in wild and cultivated sunflowers certainly causes pain in brain.

- Some good climate change news for the Atlantic croaker. Being a glass-totally-empty kinda guy I predict it tastes like shit.

Measuring diversity in Tibetan walnuts

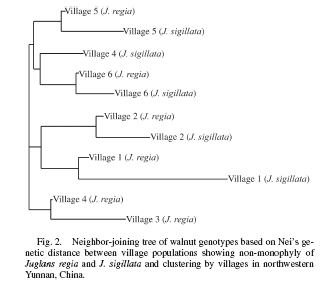

You collect leaves from 220 walnut trees of two morphologically very distinct species (Juglans regia and J. sigillata) from two unrelated groups of families of villagers in each of six different villages in Tibet. You get the gene-jockeys to do their microsatellite stuff on the leaves. You calculate the contribution of species, of the kin relationship of the growers and of village to genetic diversity. You expect the biggest genetic differences to be between species.

You are wrong.

Yes, the “species,” which look totally different, are in fact indistinguishable genetically. But there were significant differences among villages, and smaller but still significant differences between unrelated families of farmers within villages. So, you might be particularly interested in certain traits, for improvement say (and so are the farmers: walnut landraces in this part of Tibet are often named after fruit phenotypes). But — in this case — morphology is not a great guide to the totality of the underlying genetic diversity. So you can’t use it alone for conservation.

Which is also the conclusion researchers in Benin arrived at in their study of another tree, akee (Blighia sapida), also just out. A conservation and use (domestication, in this case) strategy “should target not only the morphotypes recognized by local populations but should also integrate the population genetics information.”

Does this amount to a general rule?

Nibbles: Fungi, Dogs, Protected areas, Banana, Ethiopia, Haiti

- Chromosomes can hop from one pathogenic fungus to another. Probably not a good thing.

- Dogs originated in the Middle East after all. Decide, already, will ya?

- IUCN also has a Protected Area of the Day. Genebank of the day, anyone?

- Problems with bananas in Uganda surprisingly mainly abiotic. Live and learn.

- Vaviblog celebrates Gary Nabhan’s birthday. Kinda. Which is also St Patrick’s Day? How cool is that?

- Report on Haiti’s seed security. Needs digesting.