![]() A paper by Dorian Fuller and his colleagues in this week’s Science sets out three kinds of evidence that help to pinpoint the time and place of rice domestication in eastern China. ((Fuller, D., Qin, L., Zheng, Y., Zhao, Z., Chen, X., Hosoya, L., & Sun, G. (2009). The Domestication Process and Domestication Rate in Rice: Spikelet Bases from the Lower Yangtze Science, 323 (5921), 1607-1610 DOI: 10.1126/science.1166605)) The site is Tianluoshan, just north of the current town of Hemudu on Hangzhou Bay. The water table is very high, which has preserved botanical remains and charred remains, as well as artefacts. Among those remains are more than 35,000 fragments that show how the foodways of the people changed.

A paper by Dorian Fuller and his colleagues in this week’s Science sets out three kinds of evidence that help to pinpoint the time and place of rice domestication in eastern China. ((Fuller, D., Qin, L., Zheng, Y., Zhao, Z., Chen, X., Hosoya, L., & Sun, G. (2009). The Domestication Process and Domestication Rate in Rice: Spikelet Bases from the Lower Yangtze Science, 323 (5921), 1607-1610 DOI: 10.1126/science.1166605)) The site is Tianluoshan, just north of the current town of Hemudu on Hangzhou Bay. The water table is very high, which has preserved botanical remains and charred remains, as well as artefacts. Among those remains are more than 35,000 fragments that show how the foodways of the people changed.

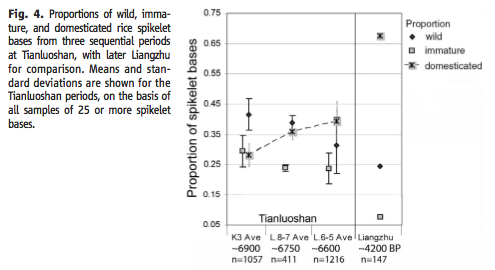

In the oldest segment, reliably dated to 4900 years BCE, acorns and water chestnuts (Trapa spp) predominate, with a few other gathered species, notably foxnuts (Euryale ferox). ((A new one on me, related to water lilies. Anyone outside Asia growing it?)). Rice is about 8% of the remains.

Three hundred years later, rice has increased to 24% of the remains, with an equally large increase in the remains of weeds typical of rice paddies.

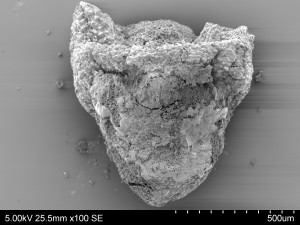

Domesticated, it should be noted, is not the same as cultivated. Domesticated types usually have a mutation that keeps the seed attached to the stalk. These non-shattering genes make the domesticated plant dependent on people to spread the seeds, and would be automatically selected for in the normal course of cultivation. As the authors note: “This trend toward an increasing proportion of domesticated types though time implies that rice was under cultivation at this time and that domestication traits were under selection.”

The paper offers clear evidence of rice cultivation and domestication 6500 years ago, but what does it say about the great japonica-indica divide? There are two views; that the two types were domesticated entirely independently, or that there was a single domestication event (selection of the non-shattering gene) which then found its way from japonica types to indica types, perhaps by crossing with wild varieties.

Fuller et al. do not treat this topic at length — that’s not what the paper is about, and Science does not allow for much discussion. I asked Fuller directly, and he said that he thinks “there is a good case archaeologically (and genetically) to be made for a separate origin in the middle Ganges”. So people there independently started to manage wild rice and to cultivate it, and then full domestication got under way around 1900 BCE, with the arrival from China of japonica types and the techniques to grow rice more effectively. He was kind enough to send another paper ((Fuller, D., & Qin, L. (2009). Water management and labour in the origins and dispersal of Asian rice. World Archaeology, 41 (1), 88-111 DOI: 10.1080/00438240802668321

And that looks like an amazingly interesting volume.)) which sets out the ideas in considerably more detail and throws fascinating light on the whole question of the cultural and social organisation needed to grow rice effectively. A parting thought from that:

We suggest that the spread of rice, which has played an important role in models of Neolithic population dispersal in Southeast Asia, may have been triggered by the development of more intensive management systems and thus have required certain social changes towards hierarchical societies rather than just rice cultivation per se.