- Anglo-Saxons may not have dropped spelt as quickly as we thought.

- The history of South Africa’s Kristaldruif grape. And where to find it.

- It was colonization that messed up Ghana’s food security. Boris take note.

- The brotherhood of manouls. They can keep it.

- Alpaca farmers out in the cold.

- CIMMYT annual report highlights the genebank.

Brainfood: Ghana cassava, Paspalum hybrids, Wild safflower, Genotyping for phenotyping

- Tracking crop varieties using genotyping-by-sequencing markers: a case study using cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). A third of cassavas found on Ghanaian farms are released varieties, though you’d never know it from just looking at the names.

- Interspecific hybrids between Paspalum plicatulum and P. oteroi: a key tool for forage breeding. P. oteroi is promising, but asexual. But there’s a way around that…

- Phylogenetic position of two endemic Carthamus species in Algeria and their potential as sources of genes for water use efficiency improvement of safflower. They’re actually in a different genus, but could still be useful.

- Genomic Prediction of Gene Bank Wheat Landraces. “…for the two populations of landraces included in this study [Mexican & Iranian], genomic predictions were generally of a magnitude that could be very useful for predicting the value of other accessions in the gene bank and that could be useful in breeding.”

Brainfood: African land use, Sorghum double, NUS trifecta, Grape hybrids, Sunflower genome, Fungi, Tree dispersal

- Africa’s Land System Trajectories 1980–2005. Biomass harvest increase has mainly come from expansion, save in the north and south.

- Status, genetic diversity and gaps in sorghum germplasm from South Asia conserved at ICRISAT genebank. Still a lot of work to do.

- Indirect estimates reveal the potential of transgene flow in the crop–wild–weed Sorghum bicolor complex in its centre of origin, Ethiopia. Could be relevant if transgenic sorghum were ever to be developed, and deployed in Ethiopia.

- Are Neglected Plants the Food for the Future? The latest hope is the SDGs.

- Potential of Kersting’s groundnut [Macrotyloma geocarpum (Harms) Maréchal & Baudet] and prospects for its promotion. Not enough mutations, apparently. Hope that won’t be an issue for the SDGs.

- Back to the Future – Tapping into Ancient Grains for Food Diversity. They need to pay their way. Enough mutations, though, I guess.

- Genomic ancestry estimation quantifies use of wild species in grape breeding. 11-76% cultivated ancestry across 60-odd hybrids, one third 50%. More back-crosses to cultivated needed.

- Genome scans reveal candidate domestication and improvement genes in cultivated sunflower, as well as post-domestication introgression with wild relatives. Wild introgressions cover 10% of cultivated genome, and there is some in every modern cultivar tested.

- MycoDB, a global database of plant response to mycorrhizal fungi. Monumental.

- Contrasting effects of defaunation on aboveground carbon storage across the global tropics. Loss of dispersal animals bad for C sequestration, but only in African, American and South Asian forests.

Nibbles: Indian ag, West African rice, Interdependence day, Animal cryo, NASA, Biopiracy?

- “…nor could they survive during inclement phases of a seasonal climate with a cheery hardiness the way our traditional varieties could.

- “How does the centrality of rice production mediate social reality among the Jola?”

- “When we say, ‘As American as apple pie,’ we think of baseball and hot dogs without ever considering not one ingredient in apple pie originates from what we call the United States.”

- “The absolute minimum we should do is preserve tissues from these animals in such a way they can be thawed and grown again.”

- “We’re botanists; we’re plant experts. Plus we had this humongous network of students, citizen scientists who were eager to do so much research that scientists at Kennedy simply didn’t have time to do.”

- “It is essential that all countries join and ratify the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol.”

The biodiversity of beer

We are extremely grateful to Ove Fosså, President of the Slow Food Ark of Taste commission in Norway, for this contribution, inspired by a recent Facebook post of his. We hope it is the first of many.

Beer is a fermented beverage usually made from just water, barley, hops and yeasts. That simple recipe can, however, produce a large variety of beers, and can harbour an immense range of biodiversity.

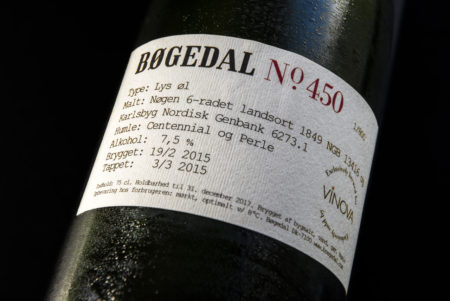

Bøgedal Bryghus is a small Danish brewery located at the idyllic 1840s Bøgedal farm. The brewery was established in 2004 and makes around 30,000 bottles per year. Each batch of around 800 bottles is different, and the batches are numbered, not named. Some of Bøgedal’s beers are made from heritage barley, sourced from the Nordic Genetic Resources Center. This barley is grown on a neighbouring farm, and malted in Denmark. They take great pride in using heritage varieties. The beer labels list both the variety names and the genebank accession numbers.

‘Chevallier’ barley provided some of the best malts and was one of the most popular varieties up until the 1930s, when other more productive varieties took over. It has been revived recently by the John Innes Institute, and used to produce a limited edition beer, the Govinda ‘Chevallier Edition’ IPA by the Cheshire Brewhouse. According to the brewer, it…

…is NOT a beer that’s about in your face HOPS! Quite the opposite, it is a beer that has been brewed to try and replicate an authentic 1830’s Burton upon Trent Pale Ale, and I have tried to manufacture it to an as authentic a process as I can, so as to try and replicate an authentic Victorian beer!

There are other beers using heritage ingredients, but they are few, and hard to find. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault has 69,000 accessions of barley as of today. Relatively few of these will be suited for malting, but still, the potensial for variation is huge.

Few beers advertise the variety of barley used. More often, you will find the name of the hop varieties on the bottle. Hops have not changed much over time, and many old clones are still in use. ‘East Kent Goldings’ has been around since 1838 and is the only hop to have a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). Hops cannot be reproduced reliably by seed, and are kept in clone collections. The Svalbard Seed Vault has only 18 seed accessions of hops. The USDA/ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository (NCGR) has a field collection of 587 accessions of hops and some further accessions in a greenhouse collection and a tissue culture collection.

An often neglected aspect of biodiversity is the diversity of microorganisms. In beer production, this is mainly brewer’s yeast. Many, probably most, breweries today use commercial yeast cultures, and are more concerned with standardisation than with local character.

Norwegian breweries have mostly copied foreign beers and thus also started out with imported yeast cultures. These eventually evolved into specific strains which are now guarded by their owners, and master cultures are stored at the Alfred Jørgensen Collection in Copenhagen, now owned by Cara Technology Ltd. They have a collection of 850 strains of brewing yeasts. The National Collection of Yeast Cultures (NCYC) in the UK holds over 4,000 strains of yeast cultures, including 800 brewing yeasts. The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) holds more than 18,000 strains of bacteria, 3,000 types of animal viruses, 1,000 plant viruses and over 7,500 yeasts and fungi.

Wild, or spontaneous, fermentation is quite trendy in winemaking today, producing ‘natural’ wines with local bacteria. In one area of Belgium, spontaneous fermentation never went out of fashion. From the Pajottenland west of Brussels comes lambic and gueuze, ‘sour’ beers, in some ways more similar to wine than to other beers. Wild fermentation can never be reproduced faithfully by commercial strains of microbes because of the diversity.

In Norway, a project to collect information on local raw materials for beer production was started in 2012. The focus is on barley varieties and hop clones, but wild herbs are evaluated, too. So far, no beers seem to have come out of this. The project does not take yeast cultures into account. Luckily, some home brewers work with local starter cultures, called kveik (literally kindling). Commercial breweries are following. The Nøgne Ø brewery has just released Norsk Høst (Norwegian Autumn), a beer based on Norwegian ingredients only, including kveik, spruce shoots, and bog myrtle. But, alas, the malt seems to be from modern barley.