- Chloroplast heterogeneity and historical admixture within the genus Malus. Three genetic networks within the genus, with the cultivated species in one of them.

- Subgenomic Diversity Patterns Caused by Directional Selection in Bread Wheat Gene Pools. Five subpopulations, dividing the European from the Chinese material. Some parts of the genome more in need of diversity than others.

- Biodiversity of Lactuca aculeata germplasm assessed by SSR and AFLP markers, and resistance variation to Bremia lactucae. Some race-specific resistance in the wild relative in Israel-Jordan, but nothing extraordinarily efficient.

- Using Multi-Objective Artificial Immune Systems to Find Core Collections Based on Molecular Markers. Very fancy math not only picks populations to maximise diversity, but also potentially at the same time minimises distance from the office.

- Assessment of ISSR based molecular genetic diversity of Hassawi rice in Saudi Arabia. It’s not just one thing.

- Minor Millets as a Central Element for Sustainably Enhanced Incomes, Empowerment, and Nutrition in Rural India. Holistic mainstreaming pays dividends.

- Minimum required number of specimen records to develop accurate species distribution models. Depends on prevalance, but 15 is a good rule of thumb.

- Microsatellite Analysis of Museum Specimens Reveals Historical Differences in Genetic Diversity between Declining and More Stable Bombus Species. Species which declined less diverse than species which did not.

The impact pathways of international genebanks

This analysis does not attempt, in any manner, to undermine the significance of the exotic germplasm material received by India during the course of time, irrespective of the source. India is a recipient of a large amount of germplasm over the period of time from multiple donors including CG genebanks and other national genebanks.

That, you may possibly remember, is from a paper on the flow of genebank material out of India. Our commentary on that paper also brought into play a compilation of data by researchers at Bioversity which quantified the movement of germplasm from India and other countries not only outwards into the CGIAR genebanks, but also in the other direction. This turned out to be just as extensive. But, of course, national programmes like India’s do not just benefit from the CGIAR genebanks through the direct access they have to the material they conserve. They also benefit from the crop improvement programmes of CGIAR centres, which churn out breeding lines and varieties using the raw materials found in their genebanks, and make them freely available to national breeders.

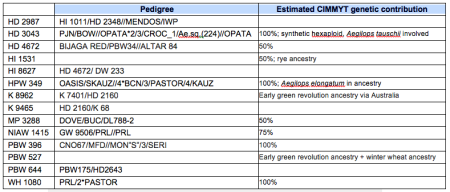

We actually saw an example of that recently when India published a list of drought and flood resistant varieties of various crops that had just been released. Through the magic of Wheat Atlas, and some expert knowledge, for both of which we’re very grateful, we can actually work out the contribution of, say, CIMMYT, to the wheat varieties on that list. Here it is, at a first, rough approximation:

Along the same lines, a recent blog post from IRRI says that

Seventy percent of all varieties released in the Philippines were strongly linked with IRRI between 1985 and 2009.

I’m sure India, and the Philippines, would agree that those international genebanks, and the crop improvement programmes they feed, are well worth having. Maybe even worth paying for.

Nibbles: Conservation genetics, African fish farming, Ecological intensification, Elderly diets, Organic breeding, Conference tweeting, Mexican maguey, African PBR

- Conservation genetics papers from Latin America, courtesy of special issue of the Journal of Heredity. No ag, but no problem.

- African aquaculture takes off. Or perhaps rises to the surface would be more appropriate.

- Expert parses what experts said “sustainable intensification” means.

- Leafy greens and wine good for oldies. Good to know.

- Student Organic Seed Symposium to discuss “Growing the Organic Seed Spectrum: A Community Approach” in a few days’ time.

- How to tweet. At scientific conferences, that is.

- Maguey genebank in the offing. Well worth tweeting about.

- Arusha Protocol on the Protection of New Plant Varieties (Plant Breeders’ Rights) adopted. Basically UPOV 1999 for Africa. But I suspect the polemics are only just starting.

Princely state of the British apple

Our readers have known for some years now that HRH Prince Charles has taken over a collection of apple varieties. Not so readers of the Sunday Times, apparently. Unfortunately, the article describing the Prince’s efforts to save the British apple is behind a paywall, so we cannot for now say whether it adds anything to the story we already knew. Maybe someone out there with a subscription can help us.

SDGs recognize agrobiodiversity and genebanks

The final version (pdf) of the Post-2015 Development Agenda was posted online about a day or so back after an all-nighter in New York.

For those who are just waking up, read the final version of the Post-2015 Development Agenda here http://t.co/c9PHgLvHCE #SDGs #Post2015

— UN DESA Sustainable Development (@SustDev) August 1, 2015

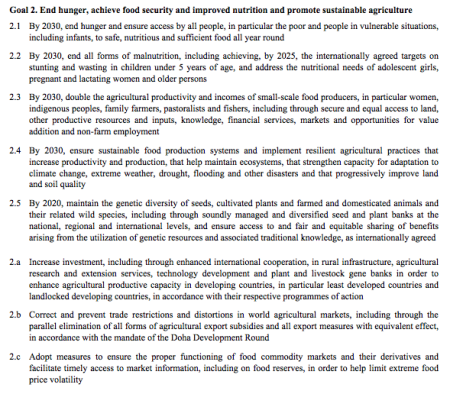

I’m glad to say Target 2.5, which highlights the importance of agricultural biodiversity, has survived intact. This includes a specific reference to genebanks, as also does an additional target (2.a) on funding. Here is the full text:

2.5 By 2020, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional and international levels, and ensure access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed

2.a Increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular least developed countries and landlocked developing countries, in accordance with their respective programmes of action

This should make it a lot easier to raise money for genebanks in the future. To see how these particular targets relate to the overall goal of ending hunger and improving nutrition, here’s the full set of targets agreed under Goal 2: