An intriguing press release from the American Chemical Society says that in some respects black rice is better than blueberries:

“Just a spoonful of black rice bran contains more health promoting anthocyanin antioxidants than are found in a spoonful of blueberries, but with less sugar and more fiber and vitamin E antioxidants,” said Zhimin Xu, Associate Professor at the Department of Food Science at Louisiana State University Agricultural Center in Baton Rouge, La. … “If berries are used to boost health, why not black rice and black rice bran? Especially, black rice bran would be a unique and economical material to increase consumption of health promoting antioxidants.”

I like black rice, and I like blueberries, but berries have made all the running lately, what with Pavlovsk and everything, so I thought I would descend into genebank database hell in search of black rice. IRRI would be the obvious first stop in such a search, but I came up empty handed. 1 Next stop, the new kid on the block, Genesys. Fun!

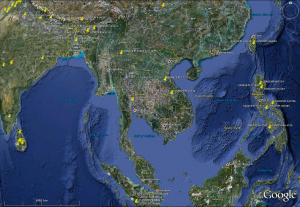

IRRI has not yet supplied Genesys with data on hull colour, but the USDA has, and there were more than 300 mapped varieties of black or purple rice. (Click the pic to embiggen.)

Dr Xu says he’d like to see Louisiana farmers growing black rice, and people in the US embrace its use. Well, as a service to them, either go to Genesys to find the variety information, or play with the Google Earth file directly.