- Koreans breed bite-sized apple for breath-freshening. Why can’t I find a picture?

- Climate change bad for genetic diversity too. Tell that to taro in Cameroon.

- Lager yeast came from South America. Thank you, Argentina! And more on long-distance microbe movement.

- Field Gene Bank of Threatened Plants from the Western Ghats threatened.

- Man’s 16-inch chili may be a record. Get your mind out of the gutter.

- The source of Turkish Red.

- “The proper use of native grasslands is to use them as grasslands…”

- Something fishy about eco-labeling.

- Japanese boffins trying to breed radiation-tolerant rice. Maybe they should look at this map in their search for parents for their crossing programme.

The birth of “genetics”

“Like other new crafts, we have been compelled to adopt a terminology, which, if somewhat deterrent to the novice, is so necessary a tool to the craftsman that it must be endured. But though these attributes of scientific activity are in evidence, the science itself is still nameless, and we can only describe our pursuit by cumbrous and often misleading periphrasis. To meet this difficulty I suggest for the consideration of this Congress the term Genetics, which sufficiently indicates that our labours are devoted to the elucidation of the phenomena of heredity and variation: in other words, to the physiology of Descent, with implied bearing on the theoretical problems of the evolutionist and the systematist, and application to the practical problems of breeders, whether of animals or plants. After more or less undirected wanderings we have thus a definite aim in view.”

The Wellcome Library celebrates William Bateson‘s 150th birthday a couple of days ago.

Old specimen is new melon crop wild relative

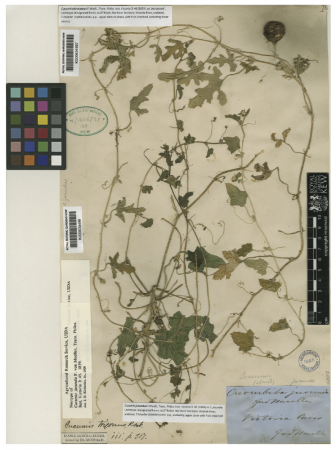

![]() Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding.

Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding.

A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

Fast forward 160 years or so, past a few older taxonomic revisions, and you get to one based on molecular analysis that splits the two previously recognized species of Cucumis in Asia, the Malesian region and Australia into 25 species. By this analysis Australia harbours seven species of Cucumis, five of them new to science. C. picrocarpus is one of the two previously recognized species, and the molecular analysis reveals that it is actually the closest wild relative of the cultivated melon, C. melo.

So what? Quite apart from the necessity to call things by their correct names, cultivated melons are besieged by many economically important pests and diseases. It seems likely that, as so often, resistance will come from a wild relative. Which means it is good to know exactly which plant is the closest wild relative. So what’s the status of C. picrocarpus in the wild? I have no idea, alas. I couldn’t find any entries in GBIF (possibly because they are all subsumed under C. melo) and with Luigi gone temporarily to ground I’m not sure where else to look. It seems a fair bet that it might need protection, although I’d be delighted to be wrong.

Nibbles: Hogwash, Onion, Herbal medicine, Coconuts

- Harry Potter upsets tree expert shock. Here’s the video.

- Botany, salad and Allium cepa.. (NB Satire.)

- Out of the Archives – Researching Herbal Medicine Then and Now. Seminar, 26 October 2011; details here.

- Coconuts: not indigenous, but quite at home nevertheless. Scientific American investigates coconut evolution and dispersal.

Brainfood: Genetic isolation and climate change, Not a Sicilian grape variety, Sicilian oregano, Good wine and climate, Italian landraces, Amazonian isolation, Judging livestock, Endosymbionts and CCD, Herbal barcodes, Finnish barley, Wild pigeonpea, Protected areas, Tree hybrids

- The impact of distance and a shifting temperature gradient on genetic connectivity across a heterogeneous landscape. Climate change bringing formerly genetically isolated populations together, possibly increasing adaptive potential.

- Intra-varietal genetic diversity of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivar ‘Nero d’Avola’ as revealed by microsatellite markers. 15 distinct genetic group among 118 plants from 30 Sicilian vineyards seems quite a lot.

- Emerging cultivation of oregano in Sicily: Sensory evaluation of plants and chemical composition of essential oils. More from Sicily. Wild is best.

- Effect of vineyard-scale climate variability on Pinot noir phenolic composition. Its complicated. But at least Pinot noir is not like Nero d’Avola. Or is it? Oh, crap.

- Landraces in Inland areas of the Basilicata region, Italy: monitoring and perspectives for on farm conservation. “Farmer-maintainers” of landraces tend to be old and isolated. Interesting stratified sampling strategy. Basilicata? They grow horseradish there, don’t they? They do indeed.

- Critical distances: Comparing measures of spatial accessibility in the riverine landscapes of Peruvian Amazonia. GIS-calculated time-based accessibility influences rural livelihoods and land use pressure. And agrobiodiversity? Apply to Basilicata next?

- A morphological assessment system for ‘show quality’ bovine livestock based on image analysis. Image of side of animal fed through neural network almost as good as experts in determining how beautiful the animal is. well there’s a triumph for science.

- Endosymbionts and honey bee colony losses? Something else to add to the list of possible causes of colony collapse disorder.

- Commercial teas highlight plant DNA barcode identification successes and obstacles. About a third of products revealed signatures of stuff that was not listed in the ingredients, but that could be due to a number of reasons.

- What would happen to barley production in Finland if global warming exceeded 4°C? A model-based assessment. Nothing good, surprisingly. Better get some new varieties, I guess.

- Cajanus platycarpus (Benth.) Maesen as the donor of new pigeonpea cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) system. Gotta love those CWRs.

- Australia’s Stock Route Network: 1. A review of its values and implications for future management. Established for movement of livestock before trucks and trains, but has lots of endangered species and communities. Great value on many fronts, in fact. Needs proper governance though.

- Should forest restoration with natural hybrids be allowed? Yep.