Mary Mangan is a scientist trained in cell and molecular biology in plant and mammalian systems, now using those skills in the field of bioinformatics, and is a co-founder of OpenHelix. Inspired by Luigi, she made a little trip and sent us this account.

Last week I decided to alter my Sunday plans based on a blog post. I was so intrigued about The Glass Orchard, the unique collection of life-sized glass models of plants on permanent display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History that I decided to walk over, weather permitting, to see it. And since Hurricane Bill decided to stay off to the east, Sunday turned out to be the perfect day.

My walk from Somerville passes through old neighborhoods (well, US old, not European old) with houses that are mostly the same vintage as the Glass Orchard, around the turn of the 20th century, give or take 20 years. As I walked I thought about the families that lived in those homes and what they might have been doing on a Sunday in August 100 years ago. I suspect they were mostly in church. I also kept an eye out for the Somerville Madonnas along the way. They are a quirky collection of mass-produced lawn sculptures with individual personalities that are really amusing in general. They are often the centerpiece of a charming garden with little cultural touches, and seem like quaint remnants of another time.

Quite honestly, that’s what I expected The Glass Orchard to be. The last exhibit I attended at the Harvard Museum — a collection of gorgeous old brass microscopes — showed many charming and attractive pieces, but they were really dated as tools of biomedical research. Similarly, I thought the flowers in the exhibit would be a sort of Victoriana frou-frou that would be nice, but quirky.

I was wrong.

These may have come from that time and place, but the Glass Flowers of Harvard are seriously remarkable — a still very effective, detailed structural look at plants and their components and mechanisms that stand the test of time. I won’t go into the history of the collection, you can find that in the linked posts. I’m just going to share my impressions below.

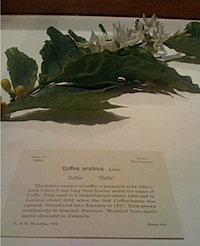

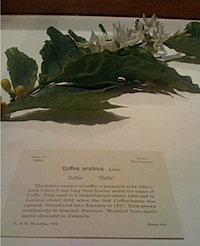

From the reading I had done, I knew there would be lovely flowers. I expected them to be some of the “pet” species of the Victorians, the irises, orchids, etc. But this display was much broader than that. There were some gorgeous specimens like blue irises. But there were also cow-parsnips — which included the root structure, and not just the green vegetation at the top. There were plenty of samples of commercially important species — coffee, tobacco, potato, and such — not just fashionable hothouse orchids of the day. It wasn’t just “pretty” plants.

From the reading I had done, I knew there would be lovely flowers. I expected them to be some of the “pet” species of the Victorians, the irises, orchids, etc. But this display was much broader than that. There were some gorgeous specimens like blue irises. But there were also cow-parsnips — which included the root structure, and not just the green vegetation at the top. There were plenty of samples of commercially important species — coffee, tobacco, potato, and such — not just fashionable hothouse orchids of the day. It wasn’t just “pretty” plants.

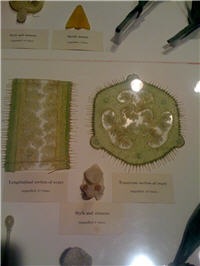

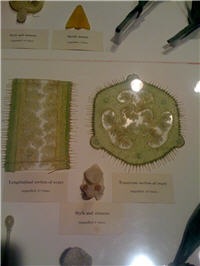

I saw glass mosses with their teeny hair-like features rendered in excruciating detail. Pollen samples at diverse magnifications were on display. There were various types and maturity of the flowers — even on the same plants. There were glass specimens of plants I have never seen — and probably never will. I’ll never think about cashews the same way ever again. I had no idea how they actually grew. Now I know.

In some cases the associated insects appeared with the plants. The Venus flytrap hosts a fly immortalized just prior to tripping the hinge on the trap. And the White Oak Wool Sower Galls included wasp larva and all.

I was surprised to see so many samples of cross-sections and higher magnifications of the plants and plant organs. In many cases the root structure details were included in the specimens. I was told by a terrific volunteer guide — also named Mary — that the father and son who created these works, Leopold and Rudoph Blaschka, had been provided a Zeiss microscope to examine the plants. It made me think of those brass ones I had seen years before. They used it very effectively.

Mary the guide also pointed me to a number of special features of the collection. She pointed out the earliest ones and it was clear that the skill of the Blaschkas ramped up rapidly. She showed me some of the samples that are showing their age, and talked about some of the curation issues around this incredibly rare and fragile stuff. We looked at some of the special details that cursory glances wouldn’t have revealed to me—like the fly I missed in the flytrap on my first pass through.

Mary the guide also pointed me to a number of special features of the collection. She pointed out the earliest ones and it was clear that the skill of the Blaschkas ramped up rapidly. She showed me some of the samples that are showing their age, and talked about some of the curation issues around this incredibly rare and fragile stuff. We looked at some of the special details that cursory glances wouldn’t have revealed to me—like the fly I missed in the flytrap on my first pass through.

The curators provide some highlights to special groups of plants — those with detailed and interesting pollination strategies, threatened plants (“plants in peril”), and food plants. Currently there is no list of all the species in the collection, but I’m told that one is in the works.

My few poorly-lit iPhone photos would never do justice to the 3-dimensional presence of these sculptures. And even the books I picked up about the glass plants — while beautifully illustrated and photographed—don’t have the same feeling as being in the room. If you are a plant lover — either professionally or as a hobbyist — I would certainly encourage you to visit this exhibition. It is stunning.

It was great to see quite a few other people there. Parents were using the models to teach their kids about pollens and fruits. Other plant lovers were equally amazed and overwhelmed with the quality and beauty of these treasures.

The workbench that the Blaschkas used to create the flowers is also on exhibit. It has a foot bellows on the bottom and a few primitive looking tools on a very plain wood surface. From my digital perspective it is nearly unfathomable that such valuable scientific educational tools as these could be created in such a low-tech way. As someone who creates contemporary educational tools for biology, I wondered if someday someone will put my laptop in a room (I’m guessing not …). I’m seriously humbled by the accomplishments of the Blaschkas and the foresight of their patrons, and impressed by the curators and volunteers who maintain and share their work today.

The last time that I felt such a reverence and touched the direct line from my career ancestors was when I worked on an Earthwatch project on the Medicinal Plants of Antiquity in Rome. We handled centuries old Medicinal Herbal texts that had beautiful illustrations, many of which are coming online now at the Smithsonian in the Renaissance Herbals collection, part of the Institute for the Preservation of Medical Traditions.

I came out of the exhibit having had a quasi-religious experience at the church of the bio-geek. And I intend to go back on another Sunday soon. I’ve already recruited potential converts as well …

Books available at the Harvard Museum shop:

The Glass Flowers at Harvard. 1992. Schultes, ((Yes, that Schultes. Ed.)) Davis, & Burger. This book has gorgeous photos of the plants, beautifully arranged and lit. But it mostly focuses on the flowers, there’s very little on the cross sections and other details. There is an introduction to the Blaschkas and more photos of the people involved and the shipping process and such. ($19.95 USD)

Drawing upon Nature: Studies for the Blaschkas’ Glass Models. 2007. Rossi-Wilcox & Whitehouse. This is a compilation of many of the field drawings that were used to create the glass versions back in the studio. Classic images with lovely details, and locations of the specimens. ($24.95 USD)

I’m adding the price so that you know, and aren’t tempted to pay $50 on Amazon for a used copy. They have plenty of new copies at the Museum store.

From the reading I had done, I knew there would be lovely flowers. I expected them to be some of the “pet” species of the Victorians, the irises, orchids, etc. But this display was much broader than that. There were some gorgeous specimens like blue irises. But there were also

From the reading I had done, I knew there would be lovely flowers. I expected them to be some of the “pet” species of the Victorians, the irises, orchids, etc. But this display was much broader than that. There were some gorgeous specimens like blue irises. But there were also  Mary the guide also pointed me to a number of special features of the collection. She pointed out the earliest ones and it was clear that the skill of the Blaschkas ramped up rapidly. She showed me some of the samples that are showing their age, and talked about some of the curation issues around this incredibly rare and fragile stuff. We looked at some of the special details that cursory glances wouldn’t have revealed to me—like the fly I missed in the flytrap on my first pass through.

Mary the guide also pointed me to a number of special features of the collection. She pointed out the earliest ones and it was clear that the skill of the Blaschkas ramped up rapidly. She showed me some of the samples that are showing their age, and talked about some of the curation issues around this incredibly rare and fragile stuff. We looked at some of the special details that cursory glances wouldn’t have revealed to me—like the fly I missed in the flytrap on my first pass through.