- People of Rapa Nui innovated as they collapsed.

- “Extinct” Bird Seen, Eaten. Sorry, National Geographic, but I can’t better that headline. Worthy of Fark.

- Kimchi madness.

- Coming to a protected are near you: moving species to save them from climate change. CWR, anyone?

- Shrinking the C footprint of traditional peanut processing. Via.

- 15 Evolutionary Gems: alas, nothing from crops, livestock. Surely domestication could have made it in there.

- “Bulgarian wine cellars have already announced that they will plant vines with the mysterious and newly recovered variety of grapes near the Orpheus tomb.”

- And more ancient wine, this time from Malta.

- Bioversity International wises up on dismal science, launches new economics webpages.

- Wild forest foods big hit at FAO booth at Lao and International Food Festival last weekend in Vientiane.

The lactose reflux problem

Stephen J. Gould said that “there’s been no biological change in humans for 40,000 or 50,000 years.” Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending beg to differ and, in “The 10,000 Year Explosion,” point to evidence for a recent acceleration in human evolution (e.g. lactose intolerance) 1 and blame it on agriculture. Not everyone agrees. I can’t help finding the idea of the end of genetic change somewhat preposterous, a priori. 2 But one must find data. Check out the interview with Cochran at 2blowhards. 3 What all this means to us here, of course, is that when we assess variation in the nutritional value of agrobiodiversity, we need to remember that that value may differ among human individuals and populations.

Agriculture in Old Japan

A woman is threshing rice stalks with a Senbakoki (åƒæ¯æ‰±ã, threshing machine), while a man is carrying straw bags balanced on a pole. In the back drying rice plants can be seen, it was customary to dry freshly cut rice plants before threshing commenced.

There aren’t that many photographs on the Old Photos of Japan website dealing with agriculture, but this is a great one, and the explanatory notes describe the rice cultivation calendar and point to a useful wikipedia article on Agriculture in the Empire of Japan. Would be interesting to match up with Vavilov’s observations on Japanese agriculture.

Nibbles: Bees, Honey, Fertilizers, Desertification, Nutrition, Decor, Mobile phones

- Bees under lots of “sub-lethal stresses.” I know how they feel.

- Hadzabe, who have been doing it for thousands of years, to be trained in honey production.

- Chinese farmers to be taught law of diminishing returns.

- “Workers at the Egyptian Desert Gene Bank in Cairo harvest and grow threatened desert species in its laboratory before replanting them to their native soils, hoping to revitalize threatened desert species.”

- Lao National Nutrition Policy puts nutrition at the centre of development.

- Economic botany and architectural fripperies.

- Got milk?

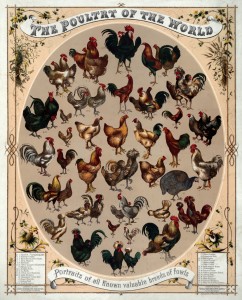

Blogging the big birthday: Chickens of the world

I’d like to think Darwin might have had this poster, or something like it, in mind as he wrote the following words in the Domestication. But then he would have acknowledged it. He was meticulous about that.

As some naturalists may not be familiar with the chief breeds of the fowl, it will be advisable to give a condensed description of them. From what I have read and seen of specimens brought from several quarters of the world, I believe that most of the chief kinds have been imported into England, but many sub-breeds are probably still here unknown. The following discussion on the origin of the various breeds and on their characteristic differences does not pretend to completeness, but may be of some interest to the naturalist. The classification of the breeds cannot, as far as I can see, be made natural. They differ from each other in different degrees, and do not afford characters in subordination to each other, by which they can be ranked in group under group. They seem all to have diverged by independent and different roads from a single type.

The poultry of the world. Portraits of all known valuable breeds of fowl. Fifty-two types of identified chickens. Chromolithograph by L. Prang & Co., Boston, ca. 1868. From the Performing Arts Poster Collection at the U.S. Library of Congress. [PD] This picture is in the public domain. Downloaded from flickr.